Clinician shortage ahead? Cardiology’s workforce prepares for a pair of silver tsunamis

With 45 percent of today’s cardiologists older than 56 and a quarter of nurses who are planning to retire aiming to do so within the year, experts predict a workforce shortage will hit when the baby boomers are increasingly in need of care.

Forecast: two silver tsunamis

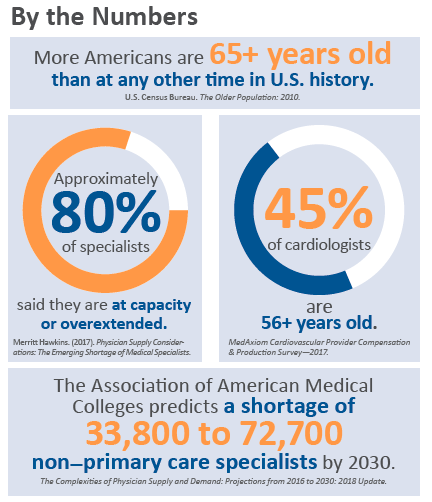

We’ve all heard some version of this prediction: The number of Americans 65 and older is on track to more than double, from 47.8 million in 2015 to 98.2 million in 2060. By then, seniors will comprise nearly 24 percent of the population, compared to 15 percent in 2015. Much has been written about how this silver tsunami of older, sicker patients will overwhelm the healthcare delivery system in general and cardiology in particular. But there’s another silver tsunami on the way: the aging healthcare workforce.

Physicians between 65 and 75 years old account for 10 percent of the active workforce, and those between ages 55 and 64 make up nearly 26 percent, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). The AAMC’s 2018 Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand report predicts physician demand will continue to grow faster than supply, leading to a projected shortfall of between 42,600 and 121,300 physicians by 2030. Projected shortfalls in non–primary care specialties range between 33,500 and 61,800.

Graying cardiology workforce

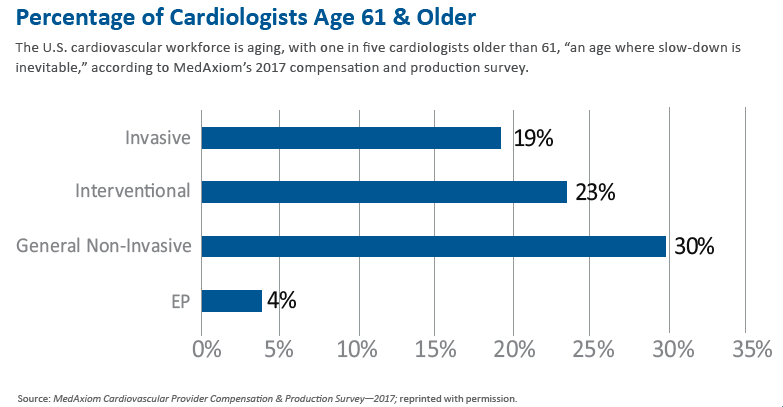

Forty-five percent of cardiologists are 56 or older, and about 20 percent are over 60, according to MedAxiom’s most recent Cardiovascular Provider Compensation & Production Survey. It’s already putting a strain on cardiology practices across the country, says Joel Sauer, MBA, vice president of MedAxiom Consulting and author of the report. “They are pedaling fast.”

General, noninvasive cardiologists are the oldest: 30 percent are over 60. That number, however, could be skewed by interventional cardiologists who, toward the end of their careers, tend to leave the lab and move into general practice.

Unsurprisingly, geographic maldistribution means this shortage is particularly acute in rural areas (J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5[7]:e002909). Overall, there are fewer cardiologists per patient 65 years and older in Midwestern and Western states than in more population-dense areas (J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68[15]:1680-9).

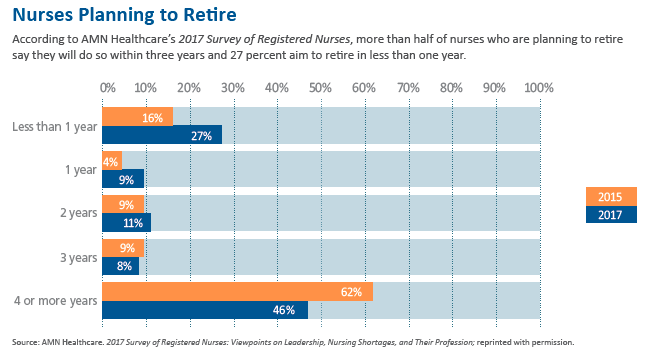

Compounding the problem, 27 percent of nurses who are considering retirement say they will stop working in less than one year, compared to 16 percent in 2015, according to the 2017 AMN Healthcare Survey of Registered Nurses. In many cardiology practices, the nursing shortage is even more acute than the physician one, Sauer reports.

One need only look at waiting rooms to sense the impact of the workforce shortage. According to Merritt Hawkins’ Physician Supply Considerations: The Emerging Shortage of Medical Specialists, the average new-patient wait time in 2017 was 21.1 days, compared to 16.6 days in 2014, based on data from 15 large metropolitan markets. The 2017 survey also measured, for the first time, wait times in 15 mid-size markets. There, it was 32.3 days.

An aging workforce, an older and sicker population, increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease and a paucity of new residency training slots may be the most obvious factors driving the shrinking cardiology workforce. They are far from the only ones.

Burned-out physicians

Burnout is often the go-to explanation for physicians leaving the profession, and it’s not unjustified: Physicians are more prone to burnout than many other professions and, in medicine, cardiologists are at higher risk—as many as half reported feeling burned out in 2016 (J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68[15]:1680-9).

The level of frustration may not be any greater than it has been recent years. The same issues—lack of autonomy, complex regulatory hurdles, electronic health records (EHRs), bureaucracy and so on—persist. However, as more physicians approach retirement age, their decisions to retire early are poised to take a greater toll on the workforce.

Claire Duvernoy, MD, senior author of the American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2017 professional life survey, suspects frustration with EHRs and health system bureaucracy may be driving some to retire early. “They remember the way it used to be—even if they don’t remember totally accurately,” explains Duvernoy, a cardiologist at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan Health System. “As they get older, there’s less tolerance for the crap that comes along with the bureaucracy.”

On the flip side, Duvernoy’s research shows that most cardiologists are generally very satisfied with their careers. “The joy of practice doesn’t change, even though they may be frustrated with aspects of the business of medicine,” she says.

Pipeline issues: IMG & women

Fewer international medical graduates (IMGs) are practicing in the U.S. than in the past, and the numbers continue to drop, says Sauer. That’s largely related to Trump-era changes to immigration policy, but he also cites another reason: As the economies in India and other countries grow and a robust middle class develops, more of those graduates are choosing to practice in their home countries. Whatever the cause, the data suggest this decline has an outsized impact on rural and underserved communities (J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69[25]:3115-7; Ann Intern Med 2017;167[8]:584-6).

Meanwhile, women continue to be underrepresented in cardiology. According to the MedAxiom report, female physicians account for just under 10 percent of the total cardiology workforce. That suggests it’s still difficult to recruit women, says Duvernoy. In fact, in the ACC report, 65 percent of the women surveyed indicated facing discrimination, compared to 23 percent of men (J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69[4]:452-62).

“If we could demonstrate we were interested in changing the field, not continuing an old boys’ network, then yes, we could recruit more women,” says Duvernoy.

‘Best near-term solution’: team-based care

A team-based approach to care will help practices deal with the inevitable silver tsunami, and evidence suggests it improves quality and access while controlling costs (J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57[9]:1123-5; 2016;68[15]:1680-9). “Team-based approaches that incorporate pharmacists, physician assistants and nurse practitioners, along with physicians, provide the best near-term solution,” Duvernoy says.

It sounds obvious, but there’s a difference between having a skilled team and deploying it most effectively, according to Duvernoy, who believes most practices are trying but fail to make optimal use of their team members. “One thing that they may not be doing optimally is to really have all individuals on their team practice to the full extent of their knowledge and capabilities.” For team-based models to work, advance practice providers (APPs) should be working at the top of their license, she explains. Too often, they don’t.

It’s not just APPs who are underutilized. In many practices, nurses end up doing clerical tasks that should be delegated to nonclinical staff , she says. She also recommends making better use of older physicians.

No call? No job, say some practices

No call? No job, say some practices

The MedAxiom survey reveals that the percentage of part-time cardiologists dropped from 13 percent to 7 percent between 2012 and 2016. That’s because, despite the overall shortage, it has become increasingly difficult for practices to absorb part-time physicians.

It’s not just the 40 percent decline in the cardologist’s productivity that occurs when he or she goes part time—although that’s significant. Call participation may play the larger role, says Sauer. Many physicians nearing retirement don’t want to take call, putting pressure on the other physicians in the practice. Sometimes, the practice needs to recruit another physician to help with call, which leaves them overstaffed during the day, he says. “We regularly hear about that from practices. Many of them now require everyone to take call.”

Duvernoy takes issue with the notion that a cardiologist who doesn’t take call will be put out to pasture. “That’s not being creative. I’m 54, and I don’t think I’m going to take call for the rest of my career,” she says. What she does expect to do is put her years of experience to work caring for patients and mentoring junior colleagues.

Adjust the compensation package to reward those who are talking call, she counsels. There are “plenty of ways to structure it to be fair. If you don’t do that, you’re not taking advantage of workforce expertise.” In an era of acute shortages, practices must harness the skills and talent of providers who are nearing retirement.

In fact, she adds, they should harness all available expertise, from allowing team members to work at the top of their licenses to improving recruitment of underrepresented groups. This has become even more critical as both silver tsunamis approach. “Be more inclusive, try to recruit all of society,” she says. “We need everybody. We should be able to do this.”