With disease rates declining, is it still worth it to screen for AAA?

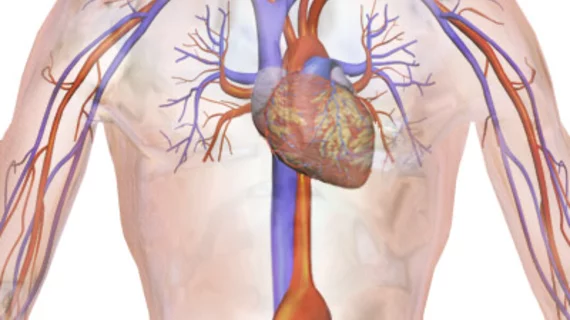

Widespread screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) may do more harm than good, according to a Swedish registry study published June 16 in The Lancet.

Nationwide screening for AAA has been implemented in Sweden and the United Kingdom, largely on the strength of four randomized trials from the 1980s and 1990s. But since then, the incidence of AAA has dropped by more than 70 percent, which ultimately shifts the benefit-to-harm balance of screening, wrote lead author Minna Johansson, MD, and colleagues.

To investigate the utility of AAA screening in more recent practice, the researchers studied 25,265 men who received testing between 2006 and 2009, matching them to 106,087 men of the same age who didn’t undergo screening. In Sweden, all men age 65 years in most areas—and age 70 in others—are invited to a one-time screening via ultrasound.

Johansson et al. calculated that two men would avoid death for every 10,000 who were offered screening. On the other hand, 49 out of 10,000 screened men would likely be diagnosed with AAA that would never cause any harm, and 19 of those would undergo a preventive surgery with all the potential complications.

Meanwhile, from the early 2000s to 2015, the rate of AAA mortality in Sweden decreased from 36 to 10 deaths per 100,000 men aged 65 to 74.

“AAA screening in Sweden did not contribute substantially to the large observed reductions in AAA mortality,” Johansson and colleagues wrote. “The reductions were mostly caused by other factors, probably reduced smoking. The small benefit and substantially less favorable benefit-to-harm balance call the continued justification of the intervention into question.”

The researchers acknowledged their relatively short follow-up period (six years) may have contributed to an underestimation of the screening benefit. More patient deaths and aortic ruptures may have occurred later on, which would have reduced the proportions of patients who were considered overdiagnosed or overtreated.

“Even if some degree of overestimation of overdiagnosis and overtreatment cannot be excluded, we do not believe that further follow-up would change the overall conclusion of our study,” the authors wrote.

But in a related editorial, Stefan Acosta, MD, PhD, said overdiagnosis “might not be as harmful as one thinks”—even if a patient knowing about a potentially safe AAA can cause anxiety.

“Although I agree that having a small AAA that needs long-term follow-up might be associated with negative psychological consequences, there could also be a window of opportunity to provide pharmacological secondary intervention (e.g., with statins, anti-platelet therapy, and blood pressure reduction) for individuals with increased burden of cardiovascular disease,” wrote Acosta, a professor of vascular surgery at Lund University in Sweden.

“Indeed, screening for AAA, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension, with the initiation of relevant pharmacotherapy if positive, reduces all-cause mortality, and some evidence suggests that this approach of multifaceted vascular screening, instead of isolated AAA screening, should be considered, although in the authors' view, this would increase the risk of overdiagnosis and overtreatment.”

Acosta agreed that a longer follow-up would have been useful and said the decreasing use of autopsies in Sweden may contribute to a larger number of fatal AAAs going undetected.

Despite the ongoing debate about the value of AAA screening, Acosta said reducing smoking prevalence is a much simpler solution. Smoking is implicated in about 75 percent of AAA cases.

“Every percentage drop in the prevalence of smoking will have a huge effect on smoking-related diseases such as cancer and AAA,” he wrote. “Primary prevention programs to reduce the prevalence of tobacco smoking is a top priority, whereas screening for AAA is not.”