The Art of Bringing in New Technology: The Real Selling Starts After You Get the Go-ahead

Editor’s Note: Real Talk is a recurring Cardiovascular Business feature. It is told from an anonymous perspective to encourage honesty and objectivity. If you have a story, experience or lesson to share, email kbdavid@cardiovascularbusiness.com.

Taking the time to build consensus and approaching the task strategically often makes the difference between success and failure. But strategy’s never a substitute for integrity.

As new technology enters the marketplace, it is always challenging to determine whether to be an early adopter. Doing so, means assuming the risk that the latest “innovation” will turn out to be a gimmick or a soon-shelved, first-generation gadget. Or your practice or system might reap big rewards if the advance turns out to be truly revolutionary.

Naturally, no one wants to be behind the curve with innovation, but it can be challenging to take the leap of faith, especially considering the amount of work needed to bring a novel product to patients and the potential liability if the outcomes don’t match the expectations. But sometimes, it really pays off.

Common story

“I really want this device,” Dr. G enthused. “Without it, our heart transplants have to stay in the hospital and continue to decompensate. This device will allow them to go home!” His excitement grew. “And it will move them to a 1A on the transplant list, which will better position us with our OPO.”

We’d struggled with the availability of organs in our local organ procurement organization, or OPO, and were keen to maximize the opportunity for our patients. Another program in the region was doing exactly that, yielding what our team felt was substandard care for their patients. I knew what a challenge this created for the team. As the service line administrator, I wanted to help Dr. G move this forward.

“Do you think our hospital will go for this?” he asked.

“I do,” I replied. “I worked with the device vendor’s finance team and have a financial model mapped out with math that sells the value of implementing.” I was starting to share his enthusiasm for being out in front. Our patients would win, we would be ahead of the competition and could reasonably expect a positive financial return.

“But I’m concerned they won’t even review the financial model if we present it straightaway,” I added. “Could you go to the VAT [value analysis team] meeting and present your idea, but without the numbers?”

Dr. G, a high-level recruit, had only been at our institution for a year and wasn’t familiar with the procurement process, whereas I knew the VAT committee had a tendency to reject financial models like this one without considering the concept. My guess was they’d humor the new guy they perceived as “Dr.-I’m-So-Famous” and send him off to do the financial work before giving him a perfunctory no based on financial infeasibility.

“OK, but aren’t they going to ask for the financials?” Dr. G asked. “Why would we delay?”

“First, you sell them on the idea of this new program, but don’t give them the price. They’ll think it’s so pie-in-the-sky, there is no way we can afford it.” I was on a roll. “If they’ll agree that we just need a positive financial plan, then we can move forward. Otherwise, it is DOA.”

“I can do that!” Dr. G’s eyes sparkled at the prospect of the challenge.

“Now, this is no guarantee that we will get final approval,” I cautioned. “But I think it’s the best chance for getting the committee to really consider the proposal.”

A week later …

“You were exactly right!” Dr. G gushed. “The two proposals before mine were shot down without a chance. Now, one of them really was a joke, but the other … well, it seemed solid, but they hardly glanced at the financials. Just an automatic, no, it won’t work”

He was so wound up it made me smile. “But with me they were almost condescending about it, like I didn’t realize they were humoring me,” he laughed. “They agreed that, if I could show the financial merit, of course they agreed it was a grand idea. They expect I’ll never follow-up.” He was on a roll. “I’ve never been so excited for a meeting in my life. Next month can’t come soon enough.”

The ultimate investment: consensus-building

The month flew by. Dr. G presented the financials to the committee. Less than 10 minutes after the meeting, the hospital’s chief financial officer called me to debunk the financial model. Fortunately, we’d adjusted it to reflect our program and payer mix and compared our methodology to an actual program of an early-adopter institution already employing the technology. The margin was solidly positive—even with several unlikely, negative assumptions built into the model to accommodate unknowns.

The CFO asked me to rerun the financials using different scenarios. With each one, our projections came out positive or at least at a break-even point. Dr. G and I had done our homework and the reward was permission to move forward.

Dr. G was ready to implement the program. But I had to apply the brakes. “Well …,” I hated spoiling the excitement. “We still have quite a bit of work left to do.”

“WHAT?!” he seemed genuinely surprised.

“We just passed the first hurdle, which is further than most proposals get,” I explained. “But, if we are going to accomplish implementation—not just buy the device—we need to leverage relationships and get everyone on board. All we have now is permission to purchase.

“We’re going to need the OR manager to purchase the ancillary supplies that you will need for each case, not just the device itself,” I continued. “Remember the exhaustive list of items? Like that ginormous catheter—that’s not standard!”

I was still overwhelmed by the supplies list. The OR team would think we’d made this up.

“Ok, so we get them the list,” he said. “How hard is that?”

“We may need to do the legwork for them,” I advised. “We need to proactively eliminate all roadblocks. I’ve seen simpler projects die because of failure to procure the necessary supplies.”

“Isn’t that their job?” he insisted.

“Um,… yeah.”

“But you are saying we need to do this for them?” he confirmed.

“We don’t have to, but do you want to leave this up to chance?” I have to admit I was taking some pleasure in showing him what administrators have to do from time to time. “In addition to the work it will take to track this stuff down, last month the CFO was putting pressure on Periop to manage their budget better. We need to present this to the OR management in a way that reduces the risk of the additional expense variance without subsequent revenue.”

We had already talked to the vendor about consignment of supply packets. “Wait, we already have this one,” Dr. G lit up. “That other company agreed to consign the device, the most expensive part. Bam!”

Dr. G saw the look on my face. “You’re going to tell me there’s more to do before we can buy?”

I nodded and reminded him that there are other key stakeholders.

“Fine, we’ll hold an implementation meeting, include everyone you’re worried about and get moving,” he said. “This cannot wait. We have approval and need to move quickly."

“Not everyone is going to be as comfortable with this technology and the changes it will bring to their areas,” I explained. “We need them to do more than quietly go along. For each stakeholder, we need to determine the choke point and then figure out how to manage around it. Every stakeholder’s engagement is critical.”

“Wait,” he interrupted. “You do this to me, too, don't you?”

The light bulb had just gone off. Dr. G was on to me. I shot him a smile. “I only use my power for good.”

“I can’t believe I didn’t notice until now,” he laughed. “OK, who’s first up for manipulation?”

Psychology of persuasion

Dr. G was good-natured, a partner I knew I would enjoy working with. He meant the comment as a compliment, but I was sensitive to the word choice.

“I know it seems like manipulation, but what we are doing is approaching the issues with the psychology of persuasion,” I said. “We will never alter facts or deceive people, but we don’t have to telegraph our strategy. It is critical that we are transparent about the impact of this technology to every person on the team, everyone whose work will be affected. In the long run, it will play in our favor. People don’t like surprises.

“Anesthesiology is up first,” I said. “We could pull them in now as an executive sponsor. Sometimes projects need the extra push from the top.”

“Before we do that, let’s try another idea,” Dr. G’s wheels were spinning. “At a conference this summer I talked to an organization whose anesthesia team published papers after implementation. I think it’s the same place our medical director trained. If we start the conversation with them from this viewpoint, we’ll get their attention.”

Dr. G leveraged the relationship and the success of the medical director’s previous program. After a little small talk, a lot of flattery and a reasonable discussion on strategy, the anesthesia team was on board.

From there, we decided on a divide-and-conquer approach. Dr. G took pathology and radiology. I had the challenge of getting the OR and ICU nurses to commit to the training needed for managing the device.

We also had to keep our CFO on board. She was an essential executive sponsor. Because she fully understood the model we were proposing and was always informed of our progress, we could have pulled her in at any point. It turned out that we didn’t have to, which earned us a chip we might need another day. She was impressed by how we tapped into relationships, leveraged authority only when necessary and used effective consensus-building techniques. She has since included us on other projects, which is a vote of confidence that Dr. G and I appreciate.

The hurdle we didn’t anticipate—there’s always at least one—came from the hospital’s Ethics Committee. Somewhere along the way, a reluctant tertiary stakeholder suggested to the Ethics Committee that Dr. G’s plan was not in the best interest of patients. Dr. G and I met with the committee together. We presented candid, straightforward facts and a compelling patient story. We demonstrated true need, the benefit for patients and the overall risk compared to available treatment options. The committee agreed that no ethics breach had occurred. In fact, they said the exact opposite, that failure to provide this treatment option to our patients when we had the capability would be untenable.

Success! We were at the finish line. Now we just had to place the first device.

Debrief

Strategically going on the offensive vs. being reactionary moved us to implementation much faster than a failed implementation restarted multiple times. Or worse, to not getting to implementation at all.

The path I navigated with Dr. G, a quick learner, was critical not only to our success but also for my self-preservation. If I’d had to butt heads all along the way, making each barrier a grandstanding “them or me” moment, the project might have been implemented but no one would have relished working with me again. And that would have rendered me ineffective to my department. As part of our project debrief, Dr. G and I discussed that.

“With all sincerity, I’m impressed by your ability to finesse people so you can accomplish goals,” he said. “How do you keep from going down the slippery slope to flat out manipulation for your own gain?”

It was a fair question.

“I’ve worked in this system for years,” I reminded him. “My integrity and reputation are crucial for my success.”

I explained the compass that guides me. “I come back to these three questions over and over. They ground me.”

- Is this what is best for our patients?

- Is this what is best for our organization?

- Would I still do this or advocate in this manner if there were no personal gain?

“If the answer is yes for all three, I am comfortable proceeding,” I continued. “If the answer is not a clear yes for the first and second, that’s my hard stop.”

“I won’t hide any facts, distort numbers or withhold data to influence our colleagues’ decisions,” I reminded him. “Yes, we choreographed the sequence of our steps to get people to really listen to our proposal before deciding. And, in some instances, we shared what others were doing, creating a competitive environment to motivate them.”

Dr. G paused and then agreed. “If we’d had to get everyone there by brute force, it wouldn’t be easily replicable. Initially, I was thinking of our persuasion campaign as sneaky and unfair. It also seemed like a waste of time to get to an outcome we could have just demanded.”

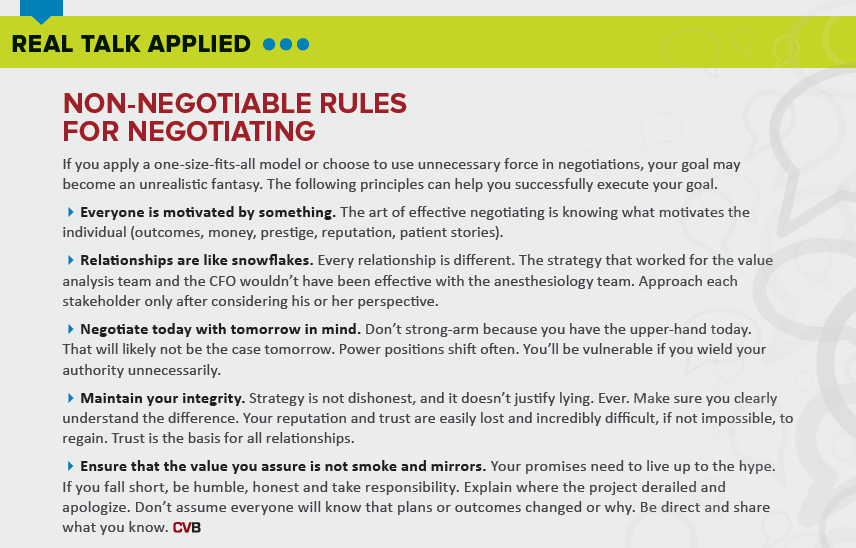

“I understand,” I replied. “That’s why we focus on strategy but always maintain integrity. The additional work—and the time it takes—to get people on board can mean the difference between a completed project and a successful project.”

There would be many more projects, reinforcing the need to maintain our reputation as positive, change-evoking, effective partners.