All Onboard: To Yield Maximum Value From New Technology, Adopt Structured Onboarding

The epiphany for Kwan Lee, MD, occurred at the end of a visit to Mayo Clinic, where he observed a complicated case. Lee, associate chief of cardiology and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and cardiology clinic at the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson, realized the radiation numbers from the lab’s X-ray system (Allura Xper FD20; Philips) were half of what his facility, with similar equipment, generated.

Lee began digging for answers and learned from discussions with experts that an ECO fluoroscopy setting available since 2007 on the platform was responsible for the dramatic radiation reduction. “No one had ever told me there was an ECO option on this machine,” he recalls. “I started using it after returning from Mayo and have never looked back.”

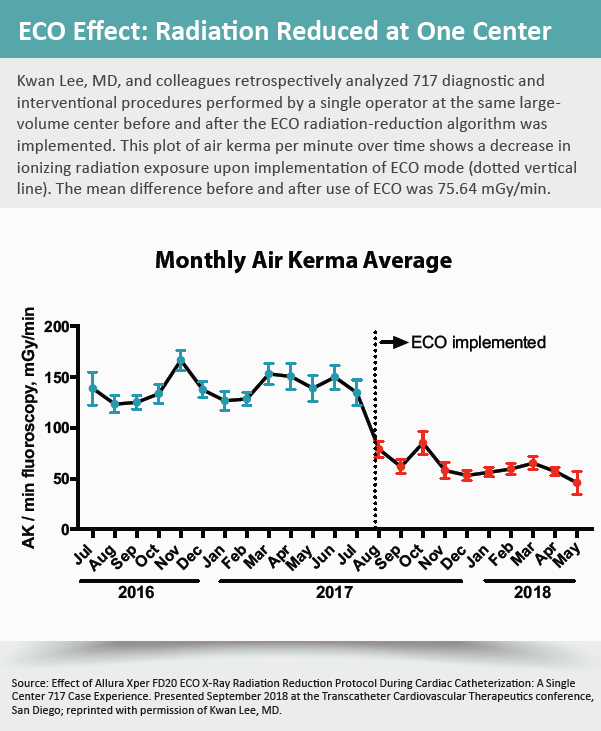

Impressed with the results, Lee conducted a retrospective analysis of diagnostic and interventional coronary procedures performed in his own lab before and after the ECO radiation reduction setting was implemented. The results, presented during a TCT.18 moderated poster session on controlling radiation exposure, showed a 54 percent reduction in ionizing radiation.

“I wasn’t aware of the feature until after the presentation,” says Louis Cannon, MD, a cardiologist and senior program director at McLaren Northern Michigan Heart & Vascular Institute and moderator of the TCT session at which Lee presented his study. “The reaction from everyone in the audience was, ‘Wow, I need to go back and check this out on my machine.’”

What they probably found was that the setting was not that mysterious—if they had just known to ask or had been informed. Accessible through the touchscreen menu, the ECO option reduces radiation through increased thickness of the X-ray beam filters for acquisition imaging, reduced frame and detector dose rates, and by setting the default fluoroscopy dose rate mode from normal to low.

“What [ECO] essentially does is knock out all the useless, low-energy X-rays that weren’t going to penetrate the patient anyway,” explains Lee, noting that the feature is the only one of its type on the market for older equipment. Newer-generation X-ray systems typically have built-in algorithms that allow for much closer monitoring and control of emitted radiation.

If there’s a downside, it’s that deploying a radiation-reduction algorithm in the laboratory will inevitably result in a decrease in image quality. After reviewing his lab’s films before and after using ECO, however, Lee labels any difference in quality “very subtle,” and adds, “Some of my colleagues disagree, but I’m also a photographer who is very particular about image quality, and I can honestly say there is no working difference.”

Need for structured onboarding

Need for structured onboarding

On closer examination, Lee’s spadework conjures up more than equipment or even radiation issues. It raises fundamental questions about how effectively new technology and equipment upgrades are onboarded in cath labs and surgical suites. Just as important, who bears responsibility for bringing physicians, technologists and other medical personnel up to speed on how equipment and devices work and the advantages—not always obvious—they can bring to areas like safety and efficacy? Rendering these questions more timely than ever is the drumbeat of sophisticated new hardware and software being introduced into interventional suites, echo labs and surgical theaters.

“If you’re in an environment where the one constant is change, then you need a structured process that allows for assessing new technologies and deciding whether or not to implement them,” says Joaquin Cigarroa, MD, chief of cardiology at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, and quality improvement committee chair for the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. That process, he elaborates, should be entrusted to the leadership of cath lab managers, radiation safety officers and physician directors supported by a dedicated committee—not just to review new technology but also to actively engage all personnel who will use it and ensure their knowledge set is complete.

The process, Cigarroa adds, should not be in the hands of equipment manufacturers and their sales representatives. “If we default to industry, then we don’t empower and enable the people who should be driving the process on a daily basis,” he says. “You don’t want salespeople who, by the way, understand aspects of their system, being charged with assessing the safety and efficacy of new technology in your laboratory.”

The debate over sales representatives in the surgical suite is touchy and contentious. Many in the field contend that company reps play a strategically important training and troubleshooting role given their detailed knowledge of the devices and equipment being onboarded, be they X-ray machines, stents, transcatheter aortic valves or left atrial appendage occluders.

Critics argue just as forcefully that cozy relationships between operators and industry agents and their companies raise profound ethical and fiscal concerns. For example, a 2013 study published in the American Heart Journal found that the on-site presence of sales representatives was associated with increased use of the company’s stents during PCI, resulting in higher procedural costs (166[2]:258-65).

Another study reported that while training opportunities provided by companies are viewed as a helpful service, “physicians who were uncomfortable with this situation noted, with frustration, that they had found no viable alternative to industry-funded courses for receiving continuing education or providing practical experience to residents.” To replace the tasks device repre-sentatives have come to perform, the study suggested hospitals should hire salaried individuals who would be “trained on a variety of devices, with no financial incentive to promote one over the other” (PLoS One 2016;11[8]:e0158510).

Given the onrush of technology from so many vendors today, Cannon believes a system of salaried trainers would be doomed to failure. What he does favor, though, is hospital clinical leaders and administrators being more attuned to daily, nuts-and-bolts issues of how equipment performs.

Speaking directly to the knowledge gap around X-ray machinery spotlighted by Lee, Cannon observes, “Perhaps the radiation safety officer should return to the lab every month, particularly through the first six months [of installation], to evaluate for radiation exposure.” At the same time, he firmly believes the medical device industry has a valuable training role to play and that excluding or restricting vendors from operating suites—a practice gaining traction—would be a “huge mistake,” resulting in loss of useful information for end-users.

Avoiding missed communications

How much of an information gap currently exists? Lee’s experience following his eye-opening visit to Mayo Clinic is revealing. In search of more information on the ECO protocol, he sought out a variety of vendors and studied whatever relevant literature he could get his hands on. “Interestingly, when you read the recent guidelines on radiation, there is no specific mention of the different technological software that’s available for reducing radiation exposure,” he says. “Everything is software driven today, and companies need to do a better job of keeping us informed.”

To underscore the potential danger of miscommunications, Cigarroa, who is a member of the FDA’s Circulatory Device panel charged with integrating new devices into clinical settings, cites aviation and the 2018 crash of an almost new Boeing 737 Max 8 off the coast of Indonesia that killed all 189 passengers and crew. Investigators suspect the onboard computer may have been operating with incorrect data from a critical plane sensor that measures wind angle. That sent the plane into a steep dive that the pilots were unable to correct due to their unfamiliarity with a new software system that overpowered manual control. After the crash, Boeing sent instructions to airlines on how pilots should react to erroneous sensor readings.

To avoid crossed communications when onboarding new medical devices, there must be an infrastructure in each hospital for assessing and incorporating new technology and, if serious lapses occur, investigation into why people were unaware, stresses Cigarroa. The assessment part should include professionals who can competently separate the “sales gimmicky from the clinically meaningful,” while the integration should involve the organized transfer of relevant knowledge and skills to users so that it becomes part of the standard operating approach.

“It has to be more than just one person who on paper has the title ‘radiation safety lead,’” Cigarroa says. “Assessing and incorporating new technology needs to be part of a robust culture of safety and innovation, along with leadership that’s constantly demonstrating to every staff member why they believe this area is so important.”