ENERGIZER EFFECT: How Term Limits & Step-down Policies Refresh a Practice

When is it time to retire? It’s a knotty, uncomfortable yet inevitable question.

Cardiologists in the U.S. generally resist setting a mandatory retirement age, a practice common in Europe. They argue that cardiologists age differently and should be treated individually.

“Some people at 65 are dynamic, innovative, high energy, involved in a lot of cutting-edge things,” says Edward T.A. Fry, MD, of St. Vincent Medical Group and Ascension Health. “Others at 65 are burned out, not open to doing new things, set in their ways, an impediment.”

TRANSPARENCY PREVENTS PROBLEMS

If age is a dubious metric for a successful succession policy, then transparent policies may be the gold standard. Whether they focus on leadership roles, stepping down or winding down, call duty or compensation, policies should be clear and applicable to all. This not only helps plan for succession but also can help deter perceptions of favoritism or unfair treatment.

ESTABLISH TERM LIMITS FOR LEADERS

For leadership positions, many cardiology practices assign term limits. Minneapolis Heart Institute sets a three-year term for leadership positions, although leaders can run for re-election and there is no limit on the number of terms they can serve, says Marc Newell, MD, chief of clinical cardiology.

St. Vincent Medical Group places a six-year term limit on its top positions. It’s long enough to get comfortable in the job and get things done but not so long as to create stagnation and stifle innovation, Fry explains. The group’s plan anticipates that the predecessor and successor will work together for a year to ease the transition.

STEP-DOWN POLICIES SMOOTH THE ROAD TO RETIREMENT

Term limits rarely work for senior cardiologists looking for paths to retirement. Typically, each individual cardiologist decides when he or she will retire, though practices are becoming increasingly proactive about this process because how and when a senior cardiologist leaves can have a significant impact on the practice and its patients.

That’s why more cardiology practices have adopted step-down or slow-down policies that allow senior cardiologists to choose, to some extent, when and how they wind down their careers. These policies usually are transparent and often are part of the cardiologist’s contract with the practice.

HOW TO HAVE “THE TALK”

Though practice leaders need to know when their senior cardiologists plan to leave, broaching the topic can be a nail-biter. This is in part because individuals approach the idea of slowing down or even ending their careers differently, Newell says.

One way to initiate the conversation is to meet with senior cardiologists to talk about the practice’s step-down policy. Minneapolis Heart Institute’s policy allows cardiologists to make decisions about which duties they want to retain and how long they want to transition into retirement, Newell says. The limit, however, is five years.

“Some people haven’t even thought about it or were not aware of what was in the contract,” Newell says.

At St. Vincent Medical Group, each physician meets with senior leaders yearly to discuss group and individual goals and plans, including asking senior partners when they plan to retire. “We plant the seed that this needs to be done thoughtfully,” Fry says.

BE PROACTIVE ABOUT CALL & COMPENSATION

BE PROACTIVE ABOUT CALL & COMPENSATION

Often the first step for a cardiologist on the way to retirement is a reduction in call or lab duty or both. The older the cardiologist, the more likely he or she is to pare back these duties, according to MedAxiom’s 2020 Cardiovascular Provider and Compensation Survey.

“I’ve had these discussions with four or five people now—they were happy and relieved,” says David X. Zhao, MD, from Wake Forest Baptist Health.

Still, reducing call duty for a senior cardiologist means the practice’s other cardiologists need to take on more call hours, and that can be tough to sell to the team. It’s easier for cardiologists to agree to taking more call duty if they recognize that it’s part of a transparent practice policy that rewards senior cardiologists and acknowledges their lifelong contributions to the practice, Zhao says.

Actively managing the distribution of call duty is an important aspect of succession planning.

At Minneapolis Heart Institute, senior partners are asked to share annual updates about their retirement plans and a year’s notice of any significant changes to allow the practice time to address gaps created by their departure, Newell says.

St. Vincent takes a three- to five-year look at call expectations to see who might be coming off the call rotation and what the recruitment needs might be, Fry says. “We try to keep it balanced so it doesn’t become an issue, so a departing doctor doesn’t increase call by 20 percent for everyone else.”

While most cardiologists welcome reduced call and some relish the prospect of performing fewer procedures or surgeries, many aren’t enthusiastic about the pay cut that accompanies such reductions. That’s one more reason for practices to be as upfront and transparent as possible about the logistics of stepping down, including how a physician’s compensation will be impacted during the winddown period.

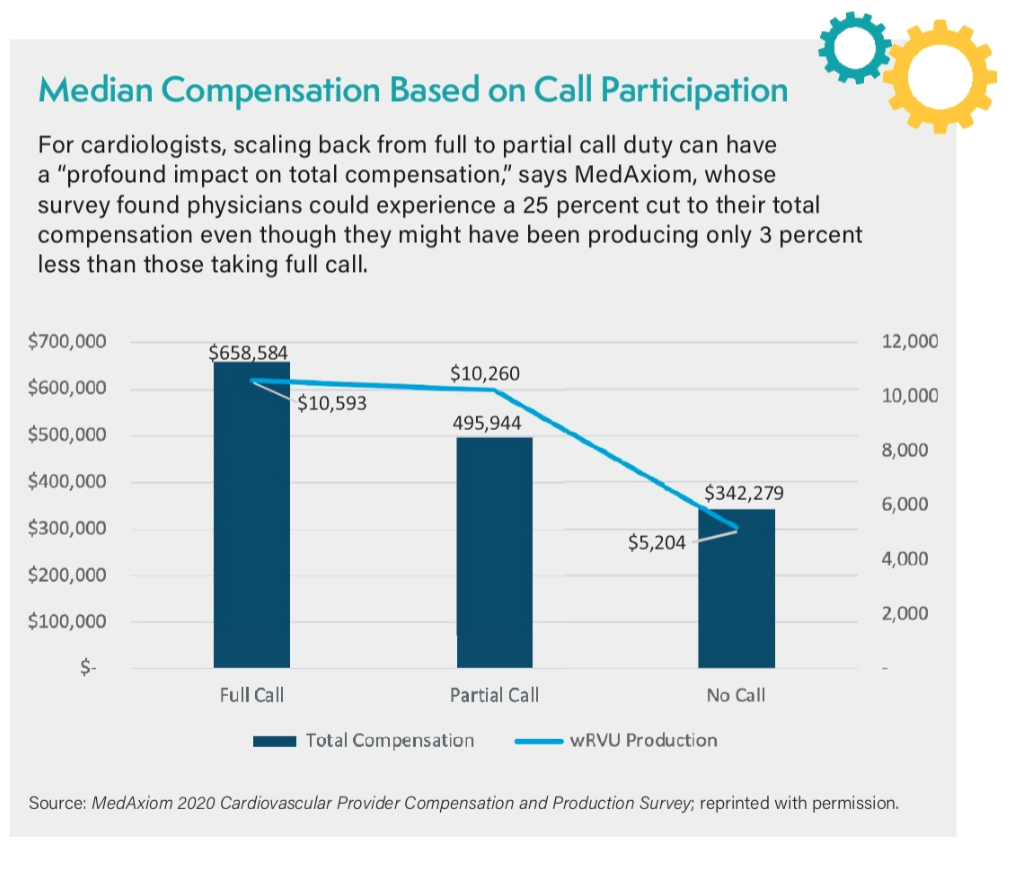

Call-duty alone can account for nearly half of a cardiologist’s total compensation, according to MedAxiom. Even just cutting back from full call to partial call duty can result in a 25 percent drop in pay (see figure on page 14).

Most cardiologists understand that when their call duty declines, so does their compensation, Zhao says. Still, the better cardiologists understand, and can plan for, the impact of reduced duties on their compensation, the more realistic they will be about their expectations around transitioning toward retirement.

MEET ‘RETIREMENT RESISTANCE’ WITH KINDNESS & CREATIVITY

There are a few cardiologists who would rather “be dragged out feet first” than step down, says Fry, who was hesitant to leave interventional practice because he enjoyed it.

After not having call duty for several nights, he decided he didn’t miss it as much as he had expected.

“It’s a young person’s game, physically and just due to constant innovation,” he says. “We try to encourage people to step back so others can move forward.”

If there are performance or quality-of-care issues, however, the strategy must involve a human resources person at a discussion with the cardiologist that details incidents and concerns, Zhao says.

“Tough decisions and tough discussions have to happen when people aren’t measuring up to the metrics that have been established,” says Mary Norine Walsh, MD, of St. Vincent Heart Center.

In general, evaluating a senior cardiologist’s ability and skills as well as the needs of the group should be part of every group review, Zhao notes. In some cases, the leadership may agree that a cardiologist should transition to fewer duties, he says.

Approaching a cardiologist with this message “must be done in a respectful way that allows them to contribute,” Zhao emphasizes. And, he notes, it helps to have established a number of retirement glide-paths for physicians to consider as they wind down their careers.