Changing of the Card: MD Employment, Exodus & Exploration

The cardiology profession, like healthcare, is in a state of flux. With large numbers of physicians at or near retirement age, there could be an exodus of talent. Today’s newly trained specialists are finding that their career path bears little resemblance to that of their elders.

For older cardiologists, you could call it the imperfect storm. Those who saw their investment portfolios tank with a souring economy a few years ago had to retrench rather than retire, despite reluctance to undergo the changes demanded in healthcare reform.

“There had been a freezing in place of practitioners after the crash,” says Jeff Goldsmith, PhD, president of Health Futures and a sociologist in the department of public health sciences at the University of Virginia, both in Charlottesville. His research includes factors that influence physician career moves. “The crash nuked a lot of the people’s retirement funding and the value of their medical real estate, which is equally important. A lot of [physicians] postponed their retirement.”

One of every five cardiologists is 60 years old or older, according to the consulting firm MedAxiom. With stock markets recovering and reform the new reality, some senior cardiologists may be poised to leave the profession and pass their shingles over to early career physicians. But those younger physicians and the environment where they practice differ from years of yore.

Debt burdens

Today’s newly minted physicians in the U.S. carry significant educational debt, a millstone that likely influences their early career decisions. Median debt levels for medical school graduates rose faster than inflation for two decades, according to a 2013 Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) report, Physician Education Debt and the Cost to Attend Medical School. Medical school debt on average has increased 6.3 percent annually since 1992. In comparison, the Consumer Price Index edged up 2.5 percent annually.

A medical school graduate who completed training in 1992 faced a median deficit from his or her education of $50,000, or a shade under $82,000 in 2012 dollars. A graduate in 2012 was in the hole financially for a median $170,000 and graduates of private institutions could expect to add another $20,000 to the I.O.U. In 2011, 86 percent of medical school graduates reported they had medical school debt, and about a third still faced bills from undergraduate schooling.

“Debt absolutely is an issue in medicine,” says James A. Youngclaus, MS, a senior education analyst at AAMC and co-author of the education debt report. “It is common among medical students to hear them talk about the amount of debt they will incur.”

Other research supports that observation. Epocrates, a digital solutions company that is part of Aetna Health, identified debt as “a major stress point” in a 2012 survey of medical students. Some 30 percent said paying off loans was among their biggest concerns in 2012, up from 17 percent in 2007.

In hock & risk averse

Physicians pursuing a cardiovascular specialty may tack three to four years on for a fellowship and then additional years of training and education for a subspecialty (Am J Cardiol 2011;108:1508–1512). That could add up to more than a decade of training after college. “This is a heavy investment in their skill set,” points out Thomas Tu, MD, director of the catheterization laboratory with the Louisville Cardiology Medical Group in Kentucky and co-chair of the Interventional Career Development Committee at the Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI).

2012/13 Income Offered

CardiologistLowAverageHigh

Non-Invasive$250,000$447,000$550,000

Invasive$300,000$461,000$675,000

Source: Merritt Hawkins 2013 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives

Early career cardiologists weighed down by debt look at employment in a different light than their predecessors. “[They] are looking at how long it takes to repay loans,” says Goldsmith. “It has been a major driver of people’s interest in salaried employment, particularly by hospitals. The amount of debt has gradually tilted the playing field away from private practice of medicine and toward corporate practice.”

Joel Sauer, vice president of Neptune Beach, Fla.-based MedAxiom Consulting, concurs. “The majority of young physicians coming out of fellowship are looking for employment,” he says, preferring job security over what could be a more financially risky independent model. “They are not looking to be entrepreneurial business owners that previous generations of cardiologists were.”

A 2013 review of physician recruitment patterns by the healthcare search company Merritt Hawkins likely squelches any doubters on that front. Only 1 percent of its 3,097 search assignments involved a solo practice in a 12-month period spanning 2012 and 2013, down from 11 percent in 2008-2009. Physician searches by hospitals dominated in 2012-2013, at 64 percent. In 2008-2009, hospital searches accounted for 45 percent of the total.

Debt also may hamstring those early career physicians who might want to buy into a physician practice. “If you were looking at a $200,000 debt and you had to pay hundreds of thousands dollars in addition—which you have to finance with debt to buy out the equity in a practice—you just aren’t going to do it,” Goldsmith says. “That model is on its way to being over, even in cardiology where the incomes are pretty robust compared to primary care.”

Getting in the black

Borrowing to invest in medical school may put limitations on career choices but it is unlikely to crush a physician, whether he or she specializes or chooses primary care. In an analysis of the economics of medical school loan repayment, Youngclaus and researchers from Boston University showed that a primary care physician with an initial debt of $160,000 could be debt-free in 10 years (Academic Medicine 2013;88[1]:16-25). Specialists with debt between $200,000 and $300,000 also could pay off loans and still have discretionary income after expenses in scenarios that placed repayments lasting from 10 to 25 years.

“The reality is the debt level is very high but the salaries are generous,” says Youngclaus. “It is not as difficult to repay when you see that six-figure [salary] number.”

The analysis placed starting salaries of $195,000 for a specialist in psychiatry or obstetrics-gynecology and $245,000 for a general surgeon. Cardiologists could expect to make higher incomes, judging from 2012-2013 salaries reported by Merritt Hawkins. Recruitment data pegged the base salary or guaranteed income at a low of $225,000 for obstetrics-gynecology and $240,000 for general surgery. The average for each specialty was $286,000 and $336,000, respectively.

The low for noninvasive cardiology was $250,000 with an average of $447,000. For invasive cardiologists, that jumped to a low of $300,000 and an average of $461,000.

Whether early career cardiologists attract such generous offers may depend on the employment model. As an employed physician, they may trade some earnings for income security. They also may choose to participate in a public service loan forgiveness plan, a federal program that offers loan forgiveness in lieu of 10 years of employment with a government or nonprofit entity.

And those who prefer to take an independent or private tack may find few doors open. “Private groups tend to be significantly more stingy on recruitment than the integrated groups,” Sauer observes. “It is getting tough to keep compensation up in the private setting and adding more physicians exacerbates that problem. You are taking the existing production that is available and splitting it by more bodies.”

Lifestyle changes

Salary is only one component in career decisions for cardiologists who recently completed their fellowships and training, Tu says. Based on his interactions with early career cardiologists through SCAI’s career development program, their most pressing concern is the nature of the job.

“Most physicians coming out [of training] realize they will not be making the same kind of financial rewards as their colleagues did in years past; there is some acceptance of that,” Tu says. “If I am not going to be earning at that level, what can I do to enjoy my job and get the most out of my career? Most physicians care about that more in the end.”

Goldsmith notes that what early career cardiologists lose in top-tier salaries may be offset with flexibility and a better work-life balance—if they can afford it. One study that examined work hours and job satisfaction found physicians in specialties with fewer work hours had higher job satisfaction (Arch intern Med 2011;171[13]:1211-1213). Physicians who specialized in cardiovascular diseases reported working on average 234 more hours annually than a family practice physician.

According to Cejka Search and American Medical Group Association’s “2011 Physician Retention Survey,” part-time employment has become increasingly popular, with 22 percent of men and 44 percent of women physicians going part time in 2011. That was up from 7 percent and 29 percent in 2005. But not all employers are willing to accept flexible or part-time arrangements. “It will narrow the practice options that are available to them [young cardiologists] to the organizations that are large enough to accommodate their scheduling needs,” Goldsmith points out.

Supply and demand also limit choices, Tu observes. Major cities, including those where many fellows train, are more likely to have an oversupply of physicians jockeying for a position. In their loan repayment analysis, Youngclaus and colleagues noted that physicians with high debt may need to consider practicing in a less expensive and perhaps less desirable region or carry their debt for a longer period of time.

“There is a very real possibility that they will have to move to a different state,” Tu says. “They may have to live in a community that is something they never considered before. Unlike many professions, medicine is one that is quite local. You go where the patients are.”

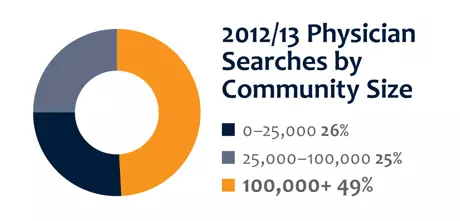

Based on the Merritt Hawkins survey, that could mean a community of 25,000 or fewer residents. That category had the most searches in 2011-2012, with 37 percent of the total, and the second most in 2012-2013, at 26 percent of the total.

A not so crystal clear ball

There are many factors that could tilt good fortune in young career cardiologists’ favor or the opposite direction. The anticipated shortage in physicians could be offset by senior cardiologists if they choose to remain engaged for many more years, whether from contentment in their work situation or another economic downturn. Healthcare reform could shift some cardiovascular patient management to the primary care setting. Payers could initiate programs that lower reimbursement or technical advancements could make some practices obsolete.

A few demographic and clinical trends are unlikely to change significantly, though. The confluence of aging baby boomers and the rise in cardiovascular diseases and risk factors such as obesity all but guarantee demand for cardiovascular services in the next decades. “Cardiology is in a good spot, long term,” Goldsmith says. “There will be tremendous demand. While there is uncertainty about the emerging practice models, cardiology is a pivotal medical discipline going forward.”

Sauer and Tu agree that cardiology’s future as a profession looks mostly secure. But they add that to be effective physicians, today’s young cardiologists, will need to archive the model of the traditional cardiologist and replace it with cardiologist as leader. And that will require a skill set that goes beyond clinical training.

Physician groups and other employers “if they are smart, are looking for someone who can blossom into a leader,” Sauer says. “We have seen in the groups with aging physicians who are slowing down or getting out [that] there is a vacuum for leadership in that next generation to fill their shoes.”

Tu, who at 11 or so years out of training describes himself as still new in his career, sees a change in the post-fellowship aspirations of cardiologists. While he sought to learn technical skills and the latest techniques in interventional cardiology, he says some of his younger colleagues are asking societies for guidance and education in healthcare economics and the business of medicine. Programs such as SCAI’s Emerging Leadership Mentorship Program, of which Tu is a graduate, are designed to help meet that need.

“We want physician leadership driving healthcare reform rather than what most doctors feel now, which is they are victims of healthcare reform and nonparticipants,” says Tu. For many cardiologists, the greatest damage from the imperfect storm is its battering of physician morale. Young physicians who understand the process and who step up to the challenge will be in a position to lead change in the future rather than follow its dictates.

“They may not have the same rewards as there were previously but they [can] have a satisfying career in medicine,” he says. “But they will require new skills. They will not be able to follow the same model as physicians before them.”

Looking at the Exit

by Laura Pedulli

With half of the 25,000-30,000 U.S. practicing cardiologists over the age of 50, and only 900 newly minted cardiologists entering the field each year, "the math isn't looking good," says Matthew Phillips, MD, president of Austin Heart in Texas.

Top that with a tougher financial environment, Medicare and EHR compliance pressures and more hospitals absorbing private cardiology practices, cardiologists increasingly look to retire early or scale down their workload at a time when their expertise and services may be needed more than ever.

Indeed, a 2012 nationwide survey of cardiologists conducted by the staffing firm Jackson Healthcare found that 45 percent of cardiologists plan to leave the practice of medicine in the next decade—a rate 11 percentage points higher than physicians as a whole. Given the potential exodus, strategies of engaging overwhelmed senior cardiologists are critical to keep them from eyeing the door.

Sinking morale

Morale issues plague cardiologists, Phillips says, who also is president of the Texas chapter of the American College of Cardiology. At a recent meeting of prominent cardiology leaders, he recalls, "I asked people if they have a morale problem. One person said, 'I'm the leader of a 20-person group, I'm 43 years old. If I could open up a bicycle shop, I'd quit today and do it.' It got worse from there."

Medicare and EHR compliance pressures, "enormously complex" billing and ever-changing medication coverage of insurance companies take a toll on cardiologists just wanting to do their jobs, he says. "We are being bludgeoned by the one more thing you have to do."

For cardiologists with decades of experience, EHR systems—which are expensive, impact workflows and interfere with direct patient interaction—are frustrating and spurring many to avoid them and think about early retirement, says Kenneth T. Hertz, a principal at Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) Health Care Consulting Group in Alexandria, Va.

Phillips agrees that cardiologists find that they are spending more time in front of a computer than the patient. "For physicians who remember that it used to not be like that, it's very distraught and frustrating," he says. "Instead of dealing with physicians who stay too long, you get a sense physicians are looking for a way to exit earlier."

Ted Bass, MD, chief of the division of cardiology at University of Florida Health at Jacksonville, echoes a similar sentiment. "As people get older and in their careers for over 20 to 25 years, all the things it takes to maintain a healthy practice do take their toll," he says. While they still enjoy the patient care aspect of their work, he says the increasingly layered bureaucracy to maintain certification and concerns about new healthcare reform requirements weigh them down.

Senior cardiologists are a group that has dictated visits for 20 or 30 years, he says. "We're also a group that looks at our patients while we talk to them. Now we sit in front of a computer, fill out templates. Some of the interpersonal stuff is gone."

He says while all senior cardiologists "get their hand held" with intensive EHR training, the issue revolves around comfort level of using computer systems at the point of care.

He notes the recent experience of one well-respected and talented senior cardiologist. "He called me up a couple of weeks ago and he said he's retiring in September. I know he loves being a physician; he was born to be a physician. So I asked him, 'What did it?' and he said, 'Electronic medical records. I just don't feel like doing it. It's not what I envisioned at this point in my life."

Planning & renegotiating

Cardiology practices and hospitals must prepare in advance for retirements and revised work arrangements for cardiologists wishing to scale down their hours, advises Hertz.

"The smart practices have developed arrangements in their employment agreement before they become issues," says Hertz.

Such an agreement would clarify what a scaled-down workload looks like, he says. For instance, if a cardiologist transitions from a partner to an employee, it will explain clearly that he or she no longer has a seat on the governance board and details revised roles and responsibilities.

Another issue is whether and when the cardiologists would remain on-call, and if they are subject to a reimbursement or compensation reduction. Also risky in that proposition, he says, is that a cardiologist scaling down on-call availability will lose compensation and income will go down as new clients are generated during these off-hour appointments.

"You have to talk about that in advance," Hertz says. If a practice or hospital is unprepared, "it's going to be a mess." He equated developing an employment agreement plan to fire drills. "You have to do it when the house is not burning."

In the cardiac division at the University of Florida Health at Jacksonville, Bass says they don't plan for retirements but they do engage in negotiations when a senior cardiologist announces he or she is looking to scale back.

On-call compensation is one area requiring negotiation. He says while maturing cardiologists practice at a very high quality, reimbursement and compensation should be adjusted for those who limit their availability.

Also, a cardiologist's responsibility to the whole group requires examination. "People who have just signed on to practice and are just starting career—I'm not sure it's their responsibility to carry older cardiologists who may not want the same workload." To that end, part-time employment may be an option, but he cautions that it can create "a whole new set of issues" when it comes to scheduling. These issues need to be hammered out, he says.

Group collaboration

Hertz says that in many systems, older cardiologists who are used to being treated with respect for their training, knowledge and education now feel like they are being treated like "widget producers"—with constant pressures to see more patients per day.

"If you get beat up like that, it's demotivating. It's harder to boost people," he says.

Bass concurs with the feeling among older cardiologists that "it has become a lot more corporate."

Phillips says with 50 percent of cardiologists within hospitals, that autonomy of the cardiologist groups can prevent many of these morale issues—especially among older cardiologists who remember a time they had more control of a practice.

For instance, Phillips says the Heart Hospital of Austin grants Austin Heart, a 45-cardiologist group, a large degree of autonomy—allowing for greater work satisfaction. "With the exception of being in compliance, the [administrators] said to us, 'We couldn't compete with you before you joined us, so our best approach is to stay out of your way,'" Phillips says.

"Unfortunately a lot of hospitals don't know how to stay out of the way of functional doctor groups," he adds.

Physician group and hospital collaboration are key, he says. "Hospitals have to understand there is a book of knowledge that physicians understand and they don't. Physicians need to know that hospitals have compliance issues and monetary concerns," he says.

He brought up the example of hospitals hiring new cardiologists without gaining the input of cardiologists already on staff. "It's horrible. When that happens the physician turns into an employee, and when the right opportunity comes, they quit."

In the case of Austin Heart, the cardiologists control the hiring process and possess total veto power. The hospital only approves the financing. With cardiologists having that power, "the chance of success [with the new cardiologist] is much higher," he says.

While senior cardiologists often are inundated with talk on patient volume and marketing, Phillips says recognizing cardiologists for the impact of their work in saving lives is essential. At meetings, Phillips talks about cases and the cardiologists' contributions to successful outcomes. "Think of how many lives you have impacted."