Experts: Inflammation key to atherosclerosis—but more drug testing needed

Therapies targeting cholesterol and inflammation have both shown the ability to reduce cardiovascular events among patients with atherosclerosis, but more evidence is needed before anti-inflammatory drugs gain widespread use similar to statins, according to a consensus statement published May 14 in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

The statement—authored by the European Society of Cardiology’s working group on atherosclerosis and vascular biology—was catalyzed by the results of the recently published CANTOS trial. This study showed the anti-inflammatory drug canakinumab cut the risk of subsequent cardiac events in heart attack survivors, even when LDL cholesterol levels weren’t significantly lowered.

“Although the results of the CANTOS trial can be considered a milestone in cardiovascular medicine, canakinumab prescription for patients with cardiovascular risk to improve their prognosis needs to overcome certain hurdles,” wrote the researchers, including lead author Jose Tunon, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at the University Hospital Fundacion in Madrid.

“In this regard, the results of the ongoing CIRT and COLCOT trials will clarify whether the cardiovascular benefit of IL-1β (interleukin-1β) blockade extends to other anti-inflammatory drugs that work through different mechanisms, as this could represent a change on the horizon of the treatment of atherosclerosis.”

The authors pointed out lipid-lowering drugs aren’t harmful even at low ranges of LDL, while anti-inflammatory drugs may compromise patients’ immune systems and leave them more susceptible to infections and sepsis.

Tunon said in a press release it would also be helpful to study anti-inflammatory drugs in a broader population than was enrolled in CANTOS. All the patients in the trial had elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of inflammation.

“LDL-lowering drugs are effective regardless of CRP levels, so we need to know if the same is true for anti-inflammatory medications,” Tunon said. “European prevention guidelines recommend lowering LDL cholesterol to less than 70 mg/dL to prevent recurrent cardiovascular events. We need a clinical trial in patients who have achieved the LDL cholesterol target of less than 70 mg/d to see if anti-inflammatory drugs can lower their cardiovascular risk even further.”

Tunon predicted anti-inflammatories won’t replace statins or other lipid-lowering medications, but said they could be prescribed as complementary therapies. But healthy lifestyle interventions such as not smoking, exercising regularly and eating a healthy diet should be the first-line defenses against atherosclerosis, he added.

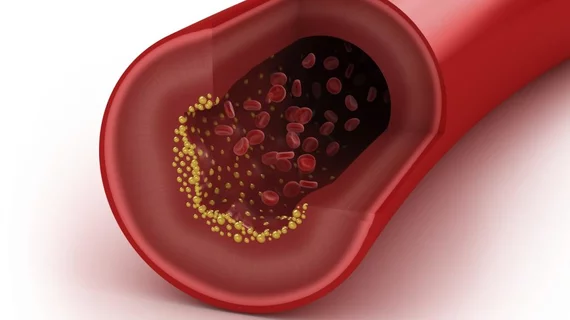

In an accompanying editorial, Viviane Z. Rocha, MD, and Raul D. Santos, MD, PhD—both with the University of Sao Paulo Medical School Hospital—described cholesterol and inflammation as “partners in crime.” Both markers are proven contributors to atherosclerosis so reducing them simultaneously should be the goal of treatment, they noted.

“After decades of studies, it is now safe to say that LDL-C and inflammation represent important causal cardiovascular risk factors, with a rich interplay between them present in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis, and in the mechanisms of their directed therapies,” Rocha and Santos wrote. “Considering the current evidence, both must be reduced to prevent ASCVD (atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease) and its ominous consequences.”