Sprinting Toward Value: HHS & Congress May Be Ready to Reconsider the Stark Law

It’s becoming evident that the Stark law is frustrating the move from volume to value. Experts expect changes that could allow health systems and practices to deploy better coordinated, team-based care and advanced alternative payment models.

We don’t usually think of regulatory reform in terms of speed, but the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is pushing a “Regulatory Sprint to Coordinated Care” that aims to remove regulatory hurdles to coordinated, value-based healthcare delivery (Federal Register, online June 25, 2018). The federal physician self-referral law, better known as the Stark law, or just Stark, is perhaps the highest of those hurdles.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has signaled its intent to loosen restrictions so hospitals and physicians can share financial risks for care coordination initiatives. This could include revising the law’s definitions of “commercial reasonableness” and “fair market value,” used by courts to determine appropriateness of business relationships.

Some adjustments can be made at the regulatory level, but substantive changes will require congressional action. Congress is listening. In July, the House Ways and Means Health Subcommittee convened a hearing titled, “Modernizing Stark Law to Ensure the Successful Transition from Volume to Value in the Medicare Program.”

A good idea at the time

Stark, which applies only to Medicare and Medicaid, prohibits physician referrals for designated health services to an entity or a person with which the physician (or his or her immediate family) has a financial relationship. Designated health services include, but aren’t limited to, imaging, radiation therapy, prosthetics, clinical laboratory services, physical and occupational therapy services, and inpatient and outpatient hospital services.

Established for a fee-for-service environment, Stark was enacted in 1989 in response to concerns that physicians who owned interests in such entities were making too many referrals to them. It also addressed gaps in the federal anti-kickback statute, which had been passed in 1972.

Because Stark is a strict liability statute, no intent to violate the law is necessary to demonstrate noncompliance.

Navigating the exceptions

Stark contains several exceptions—what the American Hospital Association (AHA) calls “haphazard combinations of exceptions originally designed for functionally independent providers, not collaborators.”

Some exceptions apply to internal relationships within a physician group. For example, to refer within the group for in-office ancillary services, the group must meet all of the criteria for a group practice, which are outlined in the regulations. “All” is the keyword. Miss one aspect, and Stark is triggered. It makes for nervous attorneys and administrators. For example, arrangements must be “commercially reasonable,” and compensation must be consistent with “fair market value.” These and other terms, critics argue, are poorly defined. Depending on the interpretation and the situation, Stark inhibits or prohibits hospitals from paying incentives to providers when they meet certain quality measures and from penalizing those who don’t.

Such uncertainty makes it difficult to navigate to value-based care.

Perception or reality? It may not matter

“There are things people would like to do now that aren’t necessarily illegal, but they would like more comfort and clarity,” says attorney James M. Daniel, Jr., a director at Hancock, Daniel & Johnson, a law firm in Richmond, Va. They want to know that care coordination and team-based payments wouldn’t be challenged “under some of the artificial definitions around fair market value and volume and value of referrals and commercial reasonableness.”

And that’s the crux of many of the concerns being raised. With this uncertainty, healthcare organizations aren’t going to move—much less sprint—to value-based models. Compounding the problem is that new payment models are being rolled out faster than case law precedent.

“Stark currently is being used as a vehicle that—whether it’s true or not from a legal barrier—is hindering value-based care,” argues C. Michael Valentine, MD, president of the American College of Cardiology (ACC).

Valentine says he’s heard countless reports from colleagues and ACC members, and he knows firsthand. A few years ago, his practice tried to set up a plan that would make 30 to 35 percent of cardiologist compensation value based, phased in over five years. “We thought it was an incredibly progressive plan that aligned with the incentives of healthcare systems over time, but the attorneys became very frightened.”

It wasn’t that the arrangement would violate Stark, Valentine explains, but that it could look that way.

That Stark inhibits value-based care is more than a little ironic, according to Joel Sauer, vice president of MedAxiom Consulting. “We need to start paying doctors differently, and that almost would negate the need for Stark,” he says.

But, in practice, it looks like Stark will need to change first. And it just might.

Twenty questions

Twenty questions

Because it is CMS rolling out those new models, the agency appears to have become more aware of the challenges Stark presents. Hence, the sprint.

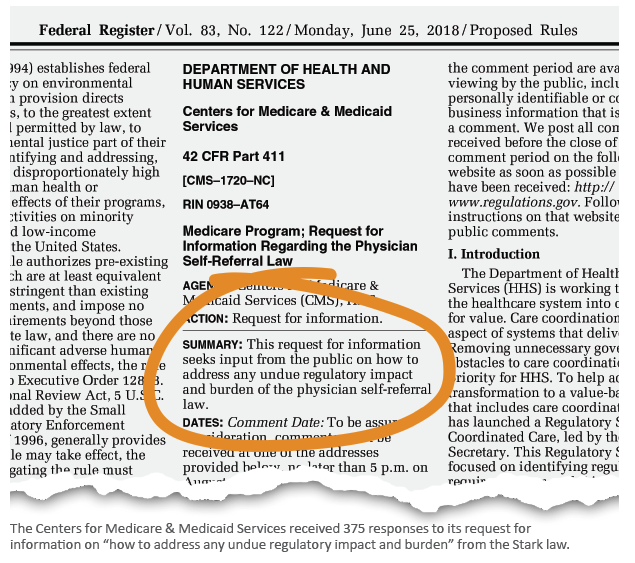

In June, CMS issued a 20-question request for information (RFI) seeking input regarding how Stark may impede care coordination. CMS asks, “Specifically, what types of financial arrangements and/or remuneration related to care integration and coordination should be protected and why?” It received 375 comments.

The AHA’s 23-page response included several recommendations around value-based care, including permitting financial rewards to physicians for care coordination.

In its response, the ACC called for a thorough review to determine whether Stark remains relevant and whether the benefits justify the regulatory burden. “We think that the answer to that question is ‘no,’” says Valentine. And if that’s the case, the ACC wants Congress and the administration to remedy the situation. It offers a list of principles on which to base such remedies. Among them:

› Allow and encourage collaboration among clinicians, as well as collaboration between clinicians and hospitals, across private practices and multiple health systems, to provide coordinated care in an appropriate manner.

› Simplify the law to reduce the exorbitant legal fees and administrative burdens imposed on clinicians. As it stands, Stark creates a huge regulatory burden—a burden that contributes to physician burnout, Valentine argues.

This time, it’s (probably) for real

There appears to be a consensus that this time Congress will significantly reform Stark. Based on the granularity of the questions in the RFI, as well as other signals coming from HHS and CMS, “this is actually a time when change might occur,” says Joseph Wolfe, an attorney at the Milwaukee office of Hall Render.

One reason that real change may be on the horizon is that healthcare organizations and payers have had time to experiment with and assess value-based models; it’s becoming clear how Stark hinders some of these newer, more advanced pay-ment models.

It’s significant that on Aug. 27, shortly after the comment period for the Stark RFI closed, the HHS Office of the Inspector General (OIG) released an RFI on the anti-kickback statute. Among the questions asked was how “value” should be defined when creating safe harbors and exceptions.

On your mark

If Congress acts next year, changes to Stark could go into effect as early as 2020. But there’s no need to wait that long, say Sauer and Wolfe.

“I think it’s important to push back on conventional wisdom when there are strong voices out there that are saying the conventional wisdom is wrong,” Sauer says. “Organizations need to challenge their assumptions a little bit and move forward.”

Sauer may be right, but being right hasn’t been enough to overcome the fear of running afoul of Stark. Still, hospitals and practices can prepare.

“If I were in the shoes of a cardiovascular practice or a healthcare organization with a significant cardiovascular practice, I would be focusing on their compensation models, especially as they relate to quality,” Wolfe says. “I would assess the components of my existing payer contracts to see that value and quality and at-risk components are being pushed down into appropriate incentives for the physicians in their compensation plans.” He also recommends building a placeholder for quality and value-based metrics into physician compensation plans now.

Because CMS is signaling a potential revisiting of Stark’s fair market value and commercial reasonableness standards, many healthcare organizations are already reexamining their compensation models and processes, so they will be ready in case there are changes, Wolfe adds.

So, what about those self-referrals?

Assuming Stark was enacted for a valid reason, will modifying it open the door to the feared trio of fraud, waste and abuse?

It’s unlikely. The very issues Stark was designed to correct could be attributed to the fee-for-service payment model, Sauer explains. Fundamentally changing the payment models eliminates many of those issues. “Absolutely,” he says, “we can modify Stark without risking opening Pandora’s box.”