Reconsidering Performance Metrics: Should 30-Day Readmissions Be Used to Evaluate PCI?

Is the 30-day readmissions metric for PCI fair or fatally flawed? The answer could have considerable financial, clinical and reputational impact for hospitals and physicians.

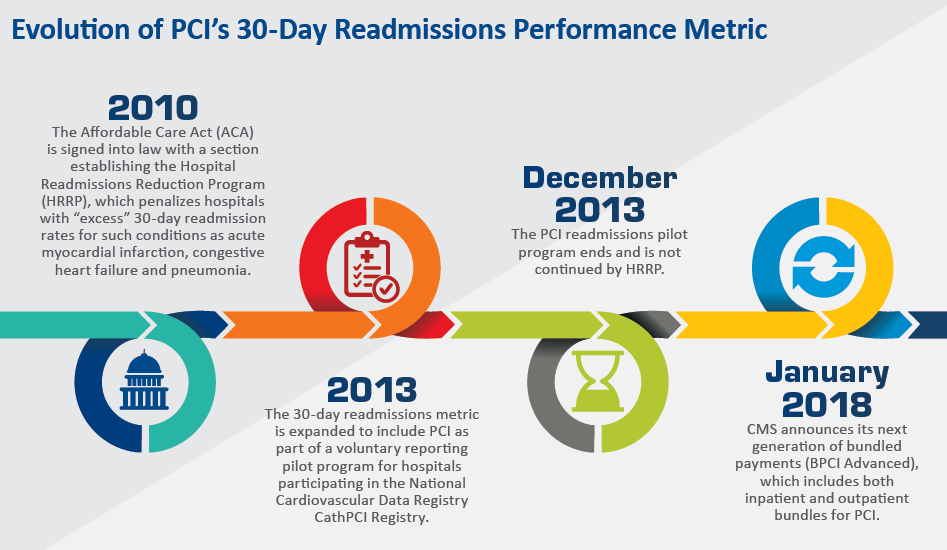

It seemed like a bold and bright idea following passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010: avoid potentially billions of dollars in healthcare expenditures by penalizing hospitals for patients readmitted within 30 days. So it was that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, which briefly applied to PCI on a pilot basis. And while that pilot was allowed to lapse, controversy over the appropriateness as well as the future of the 30-day readmissions metric for PCI has hardly died down.

The concern is not without justification. According to a growing body of literature, the majority of unplanned PCI patient readmissions bear no relationship to the original revascularization. Other important factors conspiring to land patients back in the hospital short-term are socioeconomic status, mental health, physical frailties and comorbidities. The finding has served only to fan the ongoing debate over the appropriateness of holding hospitals and physicians accountable for what happens to patients after they are discharged. Amidst the controversy, both critics and supporters ask, is 30-day readmissions a reasonable metric and, if not, what is?

“Metrics tell a story, but not a complete story,” says Robert Yeh, MD, director of the center for outcomes research in cardiology at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, and co-author of a 2014 study on the preventability of 30-day readmissions after PCI (J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3[5]:e001290). “Even if only a fraction of PCIs get readmitted, it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be thinking about them. They are potentially preventable costs, and certainly worth exploring.”

The debate essentially pits policymakers against clinicians. The former argue that readmissions act as a valuable surrogate for the overall quality of hospital care and, as such, can unmask systemic weaknesses like incomplete or improper treatment, or failure to coordinate post-discharge care. Many acute care providers, including some interventional cardiologists, argue with equal fervor that the 30-day readmissions metric is hardly an accurate or fair way to measure procedural quality when so many other factors outside of their control impinge on patient outcomes.

What seems to be emerging, however, is a judicious middle ground that recognizes the limitations of the 30-day metric but at the same time attempts to learn and grow from it. “While we as physicians might not consider [the metric] fair, it represents an important outcome for patients and is therefore something we must try to reduce,” says Mamas A. Mamas, BMBCh, DPhil, co-author of a 2018 study of more than 830,000 PCI patients (JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2018;11[7]:665-74). “We should be thinking of the PCI procedure, for example, as an opportunity to manage other conditions, which could serve to reduce complications over the longer term.”

Noncardiac causes of readmission

Noncardiac causes of readmission

Mamas and colleagues found that 9.3 percent of the PCI patients in their study had an unplanned readmission within 30 days, and that 56 percent were due to noncardiac causes. Among this cohort, chronic kidney disease, liver failure, atrial fibrillation, comorbidity burden, female sex and discharge location were the strongest predictors of early readmissions.

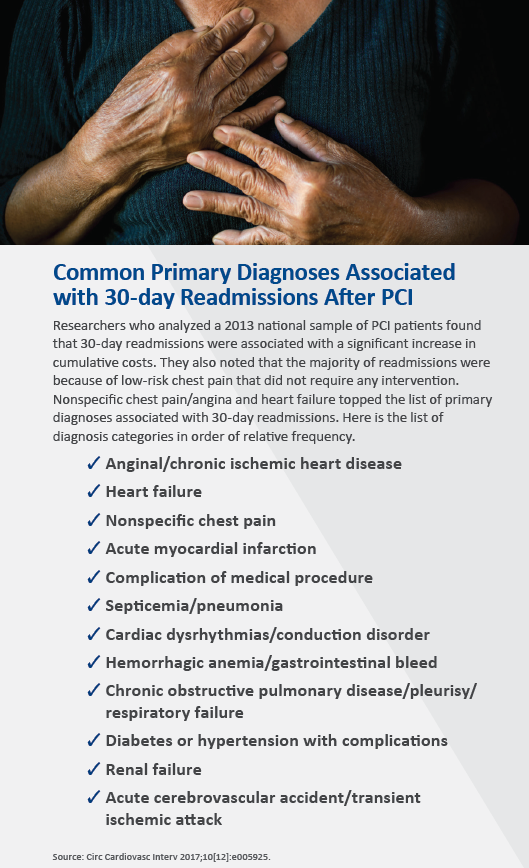

Based on findings from another prominent study, Avnish Tripathi, MD, PhD, MPH, and colleagues reported that only a small fraction of 30-day readmissions were directly traceable to the index PCI. Just as revealing, non-specific chest pain/angina was the primary diagnosis for nearly one-fourth of all readmissions (Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2017;10[12]:e005925). And therein lies an area that healthcare experts argue could make a huge difference in weaning patients away from return visits to the emergency department (ED).

“Patients who come back with chest pain are often readmitted in part because people are worried about them—they just had a heart procedure, so there must be something going on,” observes Yeh. “In the vast majority of those cases, however, the patients end up having absolutely nothing wrong with them. They get discharged without any further interventions.” Another thing that occurs, he says, is additional in-hospital testing, including stress tests, echocardiograms and recatheterizations. Tripathi and colleagues found that the mean 30-day cumulative cost for readmitted patients was $17,000 higher than for patients who were not readmitted, accounting for an approximately 45 percent increase in cumulative costs.

Few physicians or hospitals would argue that better education to inform patients and family members what to expect after discharge—and that some chest discomfort should not be alarming—could have a substantial payback. Mamas, professor of cardiology at Keele University and Royal Stoke University Hospital in the UK, strongly believes that ED physicians should be in the learning loop. “People in the ED have a lower threshold for admitting patients with noncardiac chest pain if they’ve had a PCI,” he says. “I believe that education within the ED may help reduce readmissions.”

Considering the ‘total’ patient

Are interventional cardiologists responsible for that education or, for that matter, flagging a patient’s medical and social vulnerabilities?

“Interventional cardiologists and their teams should consider patients in their entirety and not just as cardiology problems,” insists Chun Shing Kwok, MBBS, MSc, BSc, Mamas’s co-author on the burden of readmissions study and his colleague at Keele University and Royal Stoke University Hospital. “Co-existing illnesses which may not be adequately managed at the time of a patient’s PCI should be referred to an appropriate specialist, and [interventional cardiologists] should consider counseling patients on problems they may encounter and appropriate pathways for seeking professional help.”

Aware of the significant number of preventable readmissions following PCI, Massachusetts General Hospital developed a multidimensional program. During initial hospitalization, clinicians assessed patients’ readmission risk with a validated risk score and a discharge checklist that ensured access to medications and aggressive follow-up for those considered at high risk. The hospital also developed patient education videos about chest discomfort and heart failure, and established a clinic staffed by cardiology fellows to respond to patients’ problems and needs after discharge. A computerized system was created to automatically notify cardiologists whenever their patients presented in the ED within 30 days of PCI. Emergency department staff began using a risk stratification algorithm to triage patients with chest discomfort after PCI. The results? A marked decline in 30-day readmissions after PCI from 9.6 percent to 5.3 percent over a four-year period beginning in 2011 (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2016;9[5]:600-4).

Mamas emphasizes the gains to be realized from enhanced collaboration both within and outside the hospital. “I think a lot of readmissions can be avoided by closely working with other specialties during the patient’s index hospitalization, rather than when the patient has been readmitted,” he explains. “That’s like closing the stable door after the horse has bolted.” Specifically, he cites optimizing HbA1C levels in diabetic patients as a way to improve longer-term PCI outcomes, as well as the appropriate use of ACE inhibitors in people with left ventricular dysfunction.

Weighing bundled payments as a metric

The issue of physician responsibility is likely to take on fresh meaning with Medicare’s latest generation of bundled payments under the banner of value-based healthcare. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Advanced (BPCI Advanced), which began open, non-binding enrollment in January, contains 29 inpatient and three outpatient bundles, including PCI. In the eyes of a growing number of healthcare experts, bundled payments are a far better standard—or “metric”—than 30-day readmissions for judging and potentially penalizing or rewarding performance.

“If after having PCI a patient sees five doctors, makes three trips to the emergency department and has numerous complications but is never actually readmitted, I wouldn’t be saying, ‘Wow, that was fabulous,” says Ashish Jha, MD, MPH, professor of global health and health policy at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Bundled payments have the advantage of looking at everything that happened to the patient in the first 30 or 90 days and basically telling the hospital, ‘We’re going to hold you financially accountable for the entire episode.’”

Jha and other experts in the field contend that reweighting the original Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program with more quality care-focused indicators, such as symptom relief, mortality rate and infection control, would ultimately produce a far better clinical performance standard than the current 30-day readmissions metric “We do PCI to improve symptoms, so the ultimate gauge of PCI quality is really how does the patient feel afterwards,” Yeh says. “We don’t routinely measure that, however, since it’s difficult to capture. Perhaps we have to do a much better job.”