Steering Clear of Drama: When Dyad Leadership Is Out of Alignment

Editor’s Note: Real Talk is a recurring Cardiovascular Business feature. It is told from an anonymous perspective to encourage honesty and objectivity. If you have a story, experience or lesson to share, email kbdavid@cardiovascularbusiness.com.

Dyad relationships are fertile ground for drama that can affect the whole team. Recognizing your dyad’s pattern helps re-route it and create a more productive and positive work environment for everyone.

“You have to increase referrals, or your jobs are on the line!” Dr. F, my dyad partner of six months, was threatening our group of 50+ physicians, some of whom looked upset.

As he walked out, I stepped up. “He really doesn’t mean that,” I soothed. “I know you all are working hard to make this successful. Don’t worry. He’s just upset about something else. I’ll talk with him later and smooth it over.”

“It’s just unfair, what he expects from us,” one of the physicians said. I offered a few more reassurances. I felt really good about the conversation. They really saw me as their champion and would do whatever it took—for me!

My perspective changed that evening, when Dr. F and I met. “I’m really disappointed in how you undermined my message to our physicians this morning,” he said.

“But I got them calmed down! They were ready to quit,” I exclaimed.

“I hear you, but now they see you as their protector, and I’m the bad guy,” he replied. “We have to be partners and support each other. And what’s worse is they are starting to see themselves as victims.”

Then he asked, “Remember when you wanted to change how they put in their clinic orders?”

I did remember. It had been a fiasco. Several months before, Dr. F and I had agreed that, instead of having the nursing staff put in orders for procedures, the physicians would do it. I had taken considerable time streamlining the process, training the staff and educating the physicians. We’d expected increased efficiency and patient satisfaction, but the physicians decided they didn’t want to implement the change. They preferred to have patients wait until a nurse was free to enter the orders even though it caused a huge time sink in the exam room and a lot of waiting for the patient. I’d been livid when Dr. F swooped in just as we were about to go live, reversing his previous stance and siding with the physicians.

“Yes, I remember, but what does that have to do with the current situation?” I asked.

“You were so upset about the nurses putting in orders that I talked with my coach about it,” Dr. F spoke of his professional development coach. “My coach explained what I did. I got to play the hero. But it made you into the villain and, even worse, the physicians into helpless victims.

“That wasn’t my intent, but my coach was right,” he continued. “But, in this case, you did the same thing, in reverse. Now, you’re their hero and I’m the villain.”

Dr. F sighed. “I’ve noticed this is a pattern for the two of us. We need to fix it. We’re creating an unhealthy culture.”

Breaking the drama pattern

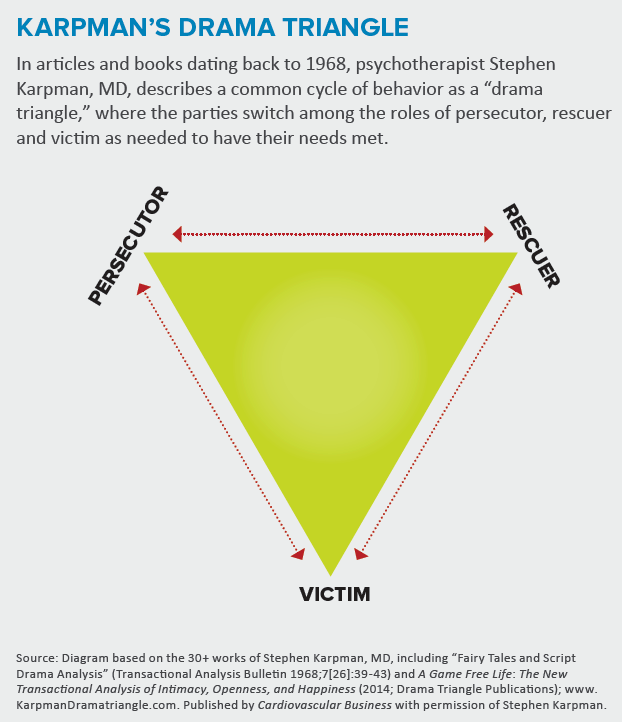

Dr. F was right, and I was surprised I hadn’t seen it myself. To have a real partnership, we needed to break the cycle. The key was understanding the “drama triangle” that Stephen Karpman, MD, has described in many publications, including A Game Free Life (Drama Triangle Publications, 2014). Once Dr. F and I looked at our dyad through Karpman’s framework, we could see that we tended to revert to the same villain/hero—what Karpman calls persecutor/rescuer—model. We also realized how our behaviors cast the physicians and staff in the role of victim. It wasn’t intentional, but we were setting the stage for drama, and everyone was playing their parts.

The pattern had to change, and it had to start with us altering our responses to each other. We set down some ground rules. Whenever either of us began feeling caught in the middle or like a third party, we’d pause and ask ourselves these questions:

- Is this something I need to be involved in? We agreed that neither of us needs to be front and center for every decision, event or action. It can be emotionally and phy-ically exhausting to try and solve everyone’s woes—a lot like riding a rollercoaster. Just because you can be involved doesn’t mean you must be involved.

- What role am I playing? Recognizing how our responses could create a drama triangle helped us understand how to avoid the pitfalls. It took time, but we began empowering individuals on the team to resolve their own problems. Some of the burden came off Dr. F and me and we mitigated the victim mentality our group had begun adopting.

- How can I support my partner? Dr. F and I needed to do a better job aligning our goals, but we also had to agree that it would be fine, perhaps even better, if we worked in parallel. We realized we didn’t have to be tethered to be successful. In fact, we soon realized we accomplished a lot more with a “divide and conquer” strategy. I began reminding myself that my partner’s success is my success, and his is mine.

Debrief

Dr. F and I have come a long way in our partnership, but we are far from perfect. Occasionally, we still have to remind each other, “I’ve got this. I just need your support.”

The relationship is solid and it has been an asset to both of us, both professionally and in the friendship we’ve developed. We communicate candidly and yet are always respectful of each other. We’ve created our own identities in the group and now have a supportive, complementary dyad partnership. The best part is that our behavior is no longer a stressor for the faculty and staff. We all suffered from the drama we were creating, and everyone benefited when we fixed it.