Tackling HFpEF: Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Presents a Diagnostic & Therapeutic Puzzle

Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), who face a high mortality risk and do not respond to conventional therapies, are changing the way clinicians think about heart failure.

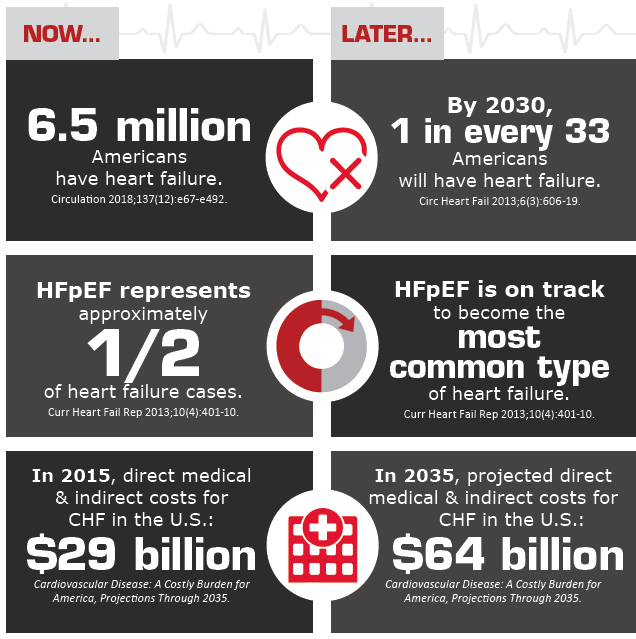

In the U.S., 6.5 million adults have heart failure, according to the American Heart Association (AHA) (Circulation 2018;137[12]: e67-e492). Once perceived as the end result of atherosclerotic heart disease in elderly patients, heart failure is increasingly affecting younger individuals, many of them women, in the form of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Approximately half of heart failure patients are believed to have HFpEF, a variant expected to become predominant by 2020 (JACC Heart Fail 2018;6[8]:619-32; Card Fail Rev 2017;3[1]:7–11).

The cardiology community has yet to agree on diagnostic criteria for HFpEF, but experts have proposed an EF threshold of 50 percent to differentiate HFpEF from heart failure with reduced EF (HFrEF; JACC Heart Fail 2018;6[8]:619-32), a classification generally used for patients with an EF under 40 percent. The prevalence of HFpEF has continued to rise over the past two decades (Card Fail Rev 2017;3[1]:7–11), whereas rates of HFrEF have remained stable or even decreased (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11[1]:1-11).

Managing the unique HFpEF patient population

Improved management of heart disease and increased survival and salvage of the myocardium after heart attack likely have a lot to do with this trend, according to Vasan S. Ramachandran, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Boston University’s schools of medicine and public health. But this tells only part of the story, says Ramachandran, who led a 2018 study showing that the growing burden of hypertension played a significant role in increasing HFpEF prevalence in the Framingham Study population (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11[1]:1-11). Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains a major cause of HFrEF, while HFpEF is more closely linked to hypertension and other conditions that are increasingly affecting the U.S. population.

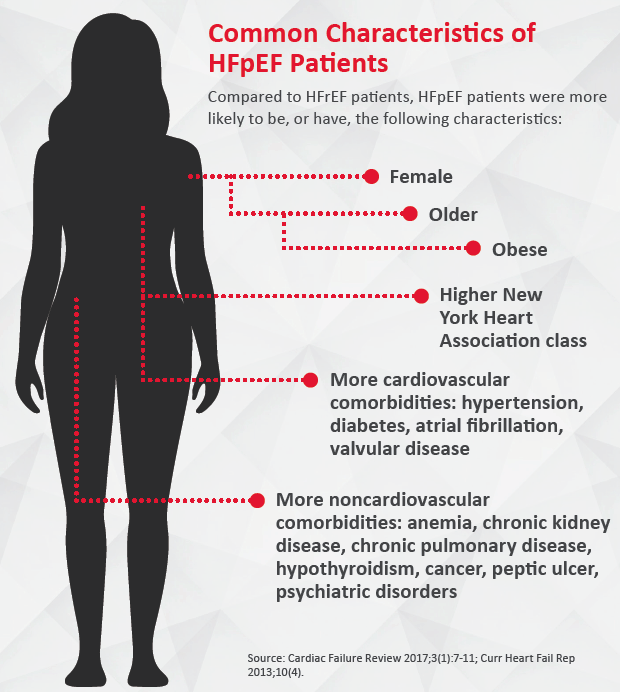

“We used to think of HFpEF as a disease of very elderly people,” says Sanjiv J. Shah, MD, professor of medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “That is still true, but we are seeing younger and younger individuals, in their 40s and 50s, with this clinical syndrome, and they tend to be obese and sometimes have severe diabetes and other comorbidities.”

HFpEF most commonly manifests in two types of patients. “One [major] sub-phenotype happens in people who are middle-aged, obese and diabetic,” Ramachandran explains. “Another sub-phenotype is seen in much older people who are hypertensive.” Although detection, treatment and control of hypertension in the U.S. have improved significantly over the past decades, they remain suboptimal, he adds.

Women increasingly susceptible to HFpEF

The growing burden of hypertension and metabolic dysfunction may also explain why women make up an increasing proportion of HFpEF patients. “A woman with both hypertension and diabetes is at very high risk later in life to develop heart HFpEF,” says Mary Norine Walsh, MD, American College of Cardiology (ACC) past president. “The other reason that the prevalence is so high and will be rising in the next few years has to do with the number of elderly people who will be alive, and the majority of them will be women.” AHA statistics on heart disease and stroke show that white females account for 60 percent of HFpEF hospitalizations.

Walsh, who is the medical director of heart failure and cardiac transplantation and director of nuclear cardiology at St. Vincent Heart Center in Indianapolis, says it is not yet clear why hypertension and diabetes have a more severe impact in women than in men in terms of heart failure. “There is some research evidence that shows that a woman’s heart remodels differently than a man’s in response to a myocardial insult, and that alone may be part of the story,” Walsh adds.

No one-size-fits-all approach

No one-size-fits-all approach

As individuals with HFpEF are swelling the ranks of patients seeking inpatient and outpatient care, cardiologists face the challenge of treating a highly heterogeneous group of patients who share some clinical manifestations but have many distinct comorbidities.

“I think we’ve been moving away from this idea that HFpEF is a single entity,” says Kishan S. Parikh, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center and the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C. “There are different flavors of it. We are starting to think of different management strategies that target those specific disorders that are associated with and may be driving the HFpEF.”

The results of recent clinical trials have confirmed that patients with different underlying diseases are unlikely to benefit from a universal approach. Certain cardiovascular drugs, particularly aldosterone inhibitors, have shown some benefit in patients with HFpEF, but conventional heart failure therapies have generally proven ineffective in this population.

Patients with HFpEF continue to have reduced quality of life, poor survival and a higher rate of mortality from noncardiovascular causes than patients with reduced ejection fraction (Curr Heart Fail Rep 2013;10[4]:401-10).

Prevention is key to HFpEF

While finding optimal therapies for HFpEF remains a challenge, cardiologists are focusing their efforts on the major comorbidities and risk factors that affect patients with HFpEF. “As we know, heart failure is not a disease, it’s a syndrome,” Ramachandran says. “When you have lung disease, liver disease, kidney disease, that combination of comorbidities creates a substrate where you are more likely to have fluid retention in the presence of normal ejection fraction.”

Current ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of HFpEF emphasize control of risk factors, such as diabetes and hypertension, along with volume management (J Card Fail 2017;23[8]:628-51).

“The best strategy for approaching the burden of HFpEF is first of all to prevent the condition,” Ramachandran says. “That means better control of high blood pressure and targeting obesity, diabetes and metabolic factors. We also have observational studies suggesting that increased physical activity is associated with a lower risk of HFpEF.”

Lifestyle plays a major role in the epidemic of comorbidities associated with HFpEF, Shah says. In addition to limited physical activity, which has been shown to drive heart failure, components found in processed foods, such as dietary phosphate, also could be catalysts of chronic disease. Recommending lifestyle changes and following up with patients to ensure they are staying on track is a first, and crucial, step in curbing HFpEF.

“There have been studies [investigating whether] we can prevent heart failure before it becomes more clinically overt by recognizing comorbid conditions and trying to have a more aggressive targeted approach toward those patients,” Parikh says. “I think the jury is still out on whether that’s going to be cost-effective.”

Targeting underlying disease

As the U.S. population continues to age, hypertension, diabetes, CAD and other chronic conditions will affect an increasingly larger number of Americans. Management of these diseases and their complications, including hospitalizations for HFpEF, is likely to trigger more healthcare utilization, Walsh predicts. Prevalence of heart failure alone is expected to increase by 46 percent by 2030 and the direct medical costs may hit $53 billion in the next two decades (Card Fail Rev 2017;3[1]:7–11; Circ Heart Fail 2016;9[6]:e003116). This costly public health issue has fueled research that is focusing on potential therapies targeting different HFpEF mechanisms.

Physicians should first try to detect underlying diseases that may be causing HFpEF in their patients, Walsh says. CAD remains a significant cause of heart failure overall, but less common conditions, such as infiltrative diseases, must also be considered. Patients with amyloidosis, for instance, commonly present with HFpEF rather than HFrEF. A therapy targeting this etiology was studied in the ATTR-ACT trial, presented at the European Society of Cardiology 2018 Congress, which found that tafamidis (Pfizer) was associated with reductions in all-cause mortality and cardiovascular-related hospitalizations in patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (N Engl J Med 2018;379[11]:1007-16).

The landscape of HFpEF management will likely be shaped by therapies targeting different pathophysiologic mechanisms, such as coronary microvascular dysfunction, which has been identified as highly prevalent in patients with HFpEF.

“In the future, there may be treatments that are generalizable to the entire group of HFpEF patients, like spironolactone in the TOPCAT trial,” says Shah, an ATTR-ACT trial investigator. “But I think what the ATTR-ACT trial shows is that if you know the exact etiology of HFpEF and you target it with a specific treatment, you can have blockbuster results.”