Challenges of Infective Endocarditis: The Opioid Crisis Hits Home & Cardiologists Can’t Go It Alone

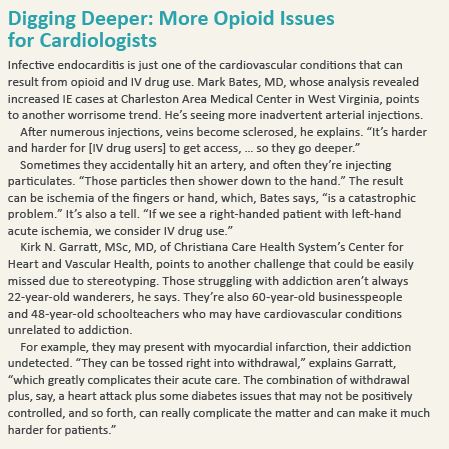

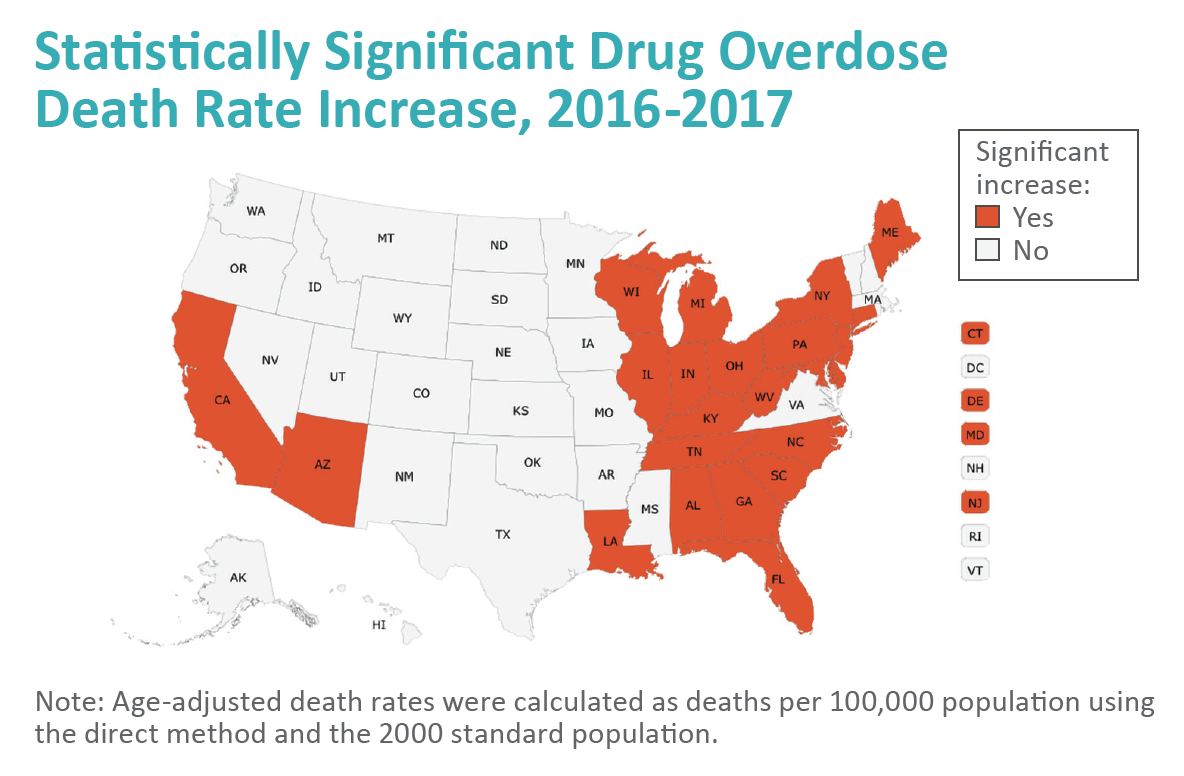

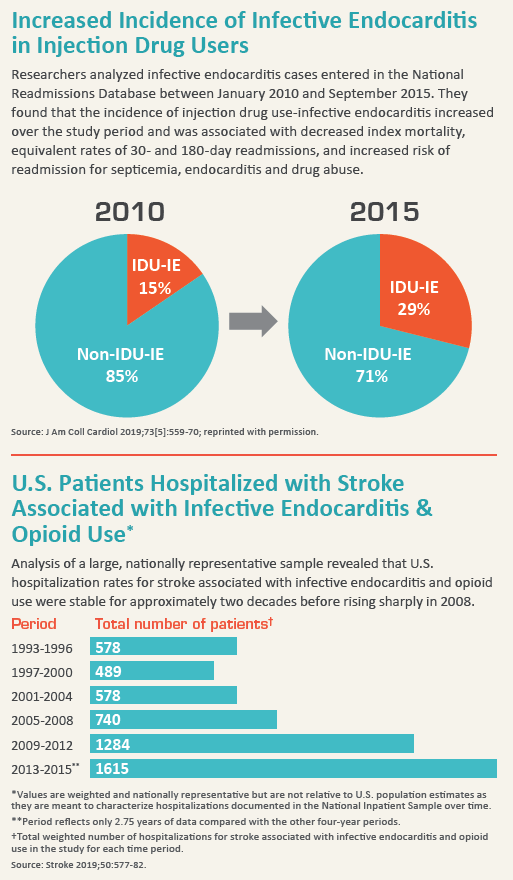

As the opioid epidemic worsens, healthcare organizations are coping with its symptoms, including dramatically increased rates of injection drug use–associated infective endocarditis (IDU-IE). Nationally, those who inject drugs comprised 18.9 percent of IE deaths in 2016, up from 9.4 percent in 1999 (JAMA Cardiol 2018;3[8]:779-80).

In Appalachia and other areas hit hard by the opioid crisis, hospitals report their IE cases are at record highs. In North Carolina, for example, IDU-IE hospitalizations increased approximately 12-fold from 2007 to 2017. Researchers estimate that, over the decade, more than 280 IDU-IE valve replacement surgeries performed in North Carolina will cost about $78 million. “The swell of [these patients] is reshaping the scope, type, and financing of health care resources needed to effectively treat IE,” the researchers wrote in the Annals of Internal Medicine (online Dec. 4, 2018).

West Virginia’s Charleston Area Medical Center also has seen a surge in IE cases, up approximately 40 percent between 2008 and 2015, according to Mark Bates, MD, director of cardiovascular research advancement. During that period, the hospital billed $17.3 million while its collections were only $3.8 million (Clin Cardiol 2019;42[4]:432-7). In 2015, the hospital lost $3.5 million to care for these patients, Bates says. “That’s just a write-off for the hospitals.”

Most communities may never see such increases, but they should nevertheless prepare themselves, he cautions, because it’s only going to get worse as the opioid crisis expands. “The problem is going to become more widespread,” he says.

Diagnostic challenge

Diagnostic challenge

Clinicians have long understood the connection between IDU and IE, and cardiologists aren’t strangers to the challenges of treating IE. Still, research suggests IDU-IE patients aren’t traditional cardiology patients. For starters, they’re younger. In one study, the median IDU-IE patient was 33 years old, compared to 56 for traditional IE patients (Ann Intern Med, online Dec. 4, 2018). IDU-IE patients also are more likely to—

- Present with right-sided infection (Postgrad Med J 2016;92[1084]:105-11);

- Have more tricuspid valve than pulmonic valve involvement (J Card Surg 2018;33[5]:260-4);

- Discharge against medical advice (Ann Intern Med, online Dec. 4, 2018);

- Be on Medicaid, self-insured or uninsured (Ann Intern Med, online Dec. 4, 2018; Clin Cardiol 2019;42[4]:432-7); and

- Be readmitted for subsequent episodes of endocarditis, septicemia and/or drug abuse (Ann Intern Med, online Dec. 4, 2018).

IDU-IE patients often don’t present with typical IE symptoms, such as a new murmur, Bates notes. “If you see a patient with a persistent fever that has pulmonary infi ltrates on their chest X-ray, look for IV drug use-related endocarditis,” he adds.

Instead of being diagnosed with IE, these patients often end up being diagnosed with pneumonia or another condition based on the abnormal chest X-ray.

But diagnosis may be the least of the challenges that cardiologists face when treating IDU-IE.

IV antibiotics quandary

Antibiotics remain the initial treatment of choice, but patients with addictions often leave the hospital before they have finished the full course.

Some clinicians opt for a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) to allow for outpatient antibiotic therapy, but that may pose a risk for patients with addiction disorders, warns Margaret A.E. Jarvis, MD, chief of addiction medicine at Geisinger in Danville, Pa., and vice president of the American Society of Addiction Medicine. “Many of these patients know peripheral vascular systems better than a lot of doctors,” she explains. “They already have an enormous craving, and then you add a PICC line. Every time they see that, they think, ‘Oh, yeah, I can use that.’ To dismiss that degree of craving—to act as though it’s something that they should have the willpower to get through … is really unkind and unrealistic.”

Another option is antibiotics taken by mouth. Some of these pills now have the same ability to fight infection as IV antibiotics, says Kirk N. Garratt, MSc, MD, chair of cardiology and medical director for Christiana Care Health System’s Center for Heart and Vascular Health. This approach simplifies patients’ care and removes the temptation of the PICC. But whether they will take the antibiotics after discharge remains a question.

The challenges of diagnosing and treating IE in addicted patients are significant, but cardiologists face a bigger dilemma: how to tackle the root cause of the IE—the patient’s substance use disorder.

Treating the IE is merely a start, Bates emphasizes. “If we don’t help them with their underlying illness—addiction—then we are only postponing the inevitable outcome: a recurrent infection of the heart, the need for heart surgery and death,” he says.

Multiple illnesses, many providers

Multiple illnesses, many providers

The physicians who spoke with CVB about IE were adamant on the importance of not treating IE in isolation. Cardiologists Bates and Garratt, addiction specialist Jarvis—they all insist that the best way forward is to also provide addiction interventions, including medication-assisted therapies and counseling. And that requires a holistic, team-based approach.

Their recommendations are echoed in a recent analysis by a team of UCLA researchers led by cardiac surgeon Peyman Benharash, MD. They say interventions for drug addiction along with coordinated addiction counseling could reduce recurrent endocarditis and drug abuse relapse in these patients (J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73[5]:559-70).

“If you have an IV drug user that comes in with vegetation on the tricuspid valve, you really need to have a multidisciplinary team that is up to date on the literature on how to care for these patients,” Bates explains. “If you try to treat them the same way you would a non-IV-drug-use patient, you’re going to miss an opportunity to turn things around.”

It’s not a new concept, Garratt notes. “Historically, cardiologists in this setting have leaned on their infectious disease colleagues to give the right medicine, and they leaned on their behavioral health colleagues to help with the addiction problem.” What has changed, he explains, is that now they ensure “all the right pieces [are] in place” by including a wider range of expertise on the care team: cardiology, infectious disease, addiction medicine, community medicine and social services, among others.

Garratt points to programs Christiana Care has implemented to address the opioid epidemic. Project Engage, for example, provides early intervention and referral to substance-use-disorder treatment programs. Staff now screen approximately 70 percent of medical admissions. Primarily through increased use of medication-assisted treatment, Christiana Care reduced 30-day readmissions for opioid withdrawal by 30 percent between October 2015 and December 2016.

“With endocarditis specifically, we believe cross-disciplinary team approaches are going to be the winning approaches, and we’re committed to that,” Garratt says, adding that the quality of the medical or surgical care will not determine their outcome. “The thing that will matter most is our ability to help them stay away from future substance abuse. That’s where we want to put our energies.”

“With endocarditis specifically, we believe cross-disciplinary team approaches are going to be the winning approaches, and we’re committed to that,” Garratt says, adding that the quality of the medical or surgical care will not determine their outcome. “The thing that will matter most is our ability to help them stay away from future substance abuse. That’s where we want to put our energies.”

As health systems develop these teams, they are to some degree figuring it out as they go, notes Jarvis. Behavioral health carveouts—when mental health benefits and clinical benefits are covered under different payers—add to the challenge. Simply arranging rehabilitation concurrent with antibiotic treatment can be difficult when each is paid by a different entity. Factor in confidentiality restrictions on top of the carveouts, and it can become challenging just to identify an IE patient who also needs addiction treatment.

With support from its legal team and patients’ consent, Geisinger has made changes “so the patient’s treatment for hypertension and diabetes resides right alongside their treatment for the use disorder,” says Jarvis. Among approximately 1,000 patients, only two declined to sign the agreement.

“One wishes that all that had been worked out 10 years ago, but that didn’t happen,” Jarvis adds, pointing to the lack of guidelines. “We are all trying to figure it all out together.”