Stirring the Pot: Cannabis & Cardiology—How & Why to Talk with Patients About Marijuana Use

There’s a good chance that some of your patients are using marijuana recreationally, therapeutically or for both purposes. And they may be afraid to tell you.

Roughly 3.1 million medical marijuana patients have registered in the U.S., according to 2019 data from the Marijuana Policy Project. Most states and the District of Columbia have legalized the substance for medical use. As of January 2020, 11 states and the District of Columbia had legalized limited recreational use.

Reports on the total number of users vary, but cannabis use is continuing to grow across all age groups. Of particular interest to cardiologists is that use in adults over age 50 is expanding fastest (Drugs Aging 2019;36[7]:655-66).

A 2019 study found that 35.1 percent of current marijuana users reported using the drug for medical reasons, 45.6 percent said they used it for nonmedical reasons and 19.3 percent indicated using it for both (JAMA Netw Open 2019;2[9]:e1911936).

In a 2020 study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, researchers reported that more than 2 million patients with cardiovascular disease were using marijuana (75[3]:320-32). So, why might cardiovascular patients be using cannabis products? For the same reasons other user cite: to address anxiety, disordered sleep, pain or lack of appetite.

Experts interviewed by CVB say that cannabis may have therapeutic benefits, but none could identify a specific cardiovascular condition relieved by cannabis. “Conversely, many of the concerning health implications of cannabis include cardiovascular diseases,” says Larry Allen, MD, MHS, professor of medicine-cardiology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora. (In Colorado, marijuana is legal for both recreational and therapeutic use.)

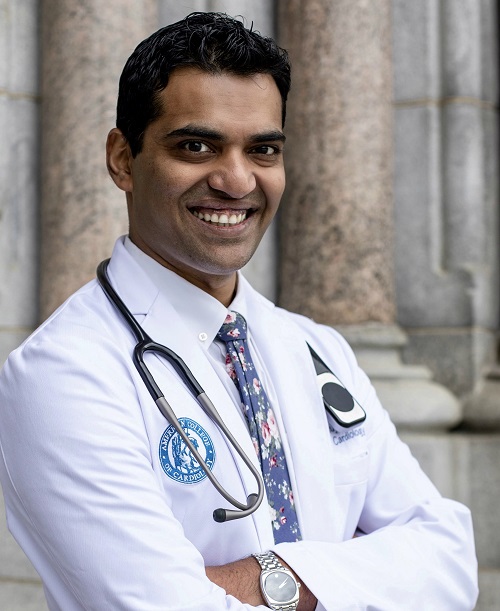

Apex Heart and Vascular Care

Passaic, N.J.

Still, cannabis consumption is growing among people with chronic conditions, points out Anuj Shah, MD, founder of Apex Heart and Vascular Care in Passaic, N.J., where cannabis is permitted for medicinal use. These are the same patients who may end up developing cardiovascular conditions, “making it difficult to really tease out the actual role cannabis might be playing vs. cannabis being the ‘innocent’ bystander—a mere confounding variable.”

And that, he and other cardiologists told CVB, is why it’s important to ask patients if they’re using cannabis products.

“It’s really easy to forget to ask about it,” acknowledges Lavanya Kondapalli, MD, assistant professor of medicine-cardiology at the University of Colorado. But it needs to be part of your risk assessment—even for patients you don’t think would indulge, she counsels. “Ask your older patients, and they will surprise you,” she says.

Taylor Lougheed, MD, an Ottawa, Ontario-based family, emergency, sport and cannabinoid physician with Canabo Medical Clinic, which specializes in medical cannabis care, has seen seniors’ interest in cannabis grow since it was legalized throughout Canada. “With the growing interest in cannabis products in the older population, we are also seeing a growing need for patient education that includes looking at the unique risks that may be seen in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities.”

Limited research raising CV concerns

In the U.S., cannabis remains a schedule 1 substance, meaning the federal government currently grants it no accepted medical use and believes it has high potential for abuse. Thus, conducting rigorous research is difficult; however, case reports and preliminary studies have indicated recreational marijuana use is associated with an array of cardiovascular problems, including stroke, heart attack, artery dissection, vasospasm, arrythmia, structural changes and sudden cardiac death. For example—

› Structural changes to the heart: A U.K. observational study found regular cannabis use (daily or weekly use for the previous five years) was “independently associated with adverse changes in left ventricle size and subclinical dysfunction compared with rare/never cannabis use.” The authors warn that their findings should be “interpreted with caution,” and—a common refrain in this research area—further research is required (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, online Dec. 18, 2019).

› Stroke: Speaking to CVB, several experts noted the risk of stroke, especially among young people. One observational study suggested significantly higher stroke risk in young marijuana users compared to nonusers, with even greater concern among those who use the drug at least 10 days a month (Stroke 2020;51[1]:308-10).

› Arrythmia: Chronic cannabis use or abuse worsens hospitalization outcomes in arrhythmic patients, according to research published in Cureus (2019;11[9]:e5607). Although the rate of arrhythmias overall is declining, the authors found a statistically significant rising trend of arrhythmia hospitalizations with cannabis use disorder in those 45 to 54 years old, males and Caucasians.

Additionally, people diagnosed with cannabis use disorder were more likely to be hospitalized for arrhythmias, according to preliminary data presented at the American Heart Association’s 2019 scientific sessions (poster Mo2053). The study looked only at young African American men, and the authors cautioned that the finding suggests a trend, not cause and effect.

› Drug-drug interactions: Lougheed cites case reports of increases in INR in patients taking warfarin and using cannabis products. A 2019 literature review found that “the available, although sparse, data suggest that use of cannabinoids increases INR values in patients receiving warfarin.” The authors recommended that patients taking warfarin should be cautioned against using cannabis (Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2019;124[1]:28-31).

Results may vary

How patients are consuming marijuana might turn out to be as important as how much and how often. The mechanism of delivery can make a tremendous difference because absorption rates vary, even among edibles, according to Kondapalli. “One of the problems of the currently unregulated landscape is that cannabis isn’t just one thing,” she explains. “For example, synthetic cannabinoids are extremely potent. The more your patients can tell you about what they are ingesting or inhaling, the better.”

While all statins are essentially the same, she says, all types of cannabis are not. It’s unregulated, so clinicians can’t know exactly what people are taking. Her advice is to be honest with patients about the knowledge gaps. “Unlike tobacco, we don’t have the data,” she says. “This is uncharted territory.”

Worse than tobacco?

Compared to the decades of research on the dangers of cigarette smoke, the field is just beginning to understand the effects of marijuana smoke exposure—both first- and second-hand smoke.

Matthew Springer, PhD, professor of medicine in the University of California-San Francisco’s division of cardiology, is among those researching the cardiovascular effects of marijuana smoke. “Marijuana and tobacco smoke are very similar,” he explains, “Tobacco smoke contains thousands of chemicals, and the evidence is very strong that just about all the chemicals found in one type are also in the other—not including cannabinoids and nicotine-related molecules.”

Springer says physicians should view cannabis not only as a drug but also as another source of smoke exposure. In fact, cannabis smoke may be worse for the cardiovascular system than tobacco. One of his studies found that rats’ blood vessels took three times longer (about 90 minutes) to recover function after only a minute of breathing secondhand marijuana smoke vs. recovery (about 30 minutes) after a minute of breathing secondhand tobacco smoke. (J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5[8]:e003858).

He advises clinicians to include cannabis in discussions about smoking and secondhand exposure to tobacco smoke: If they are counseling their patients to not smoke and to avoid secondhand smoke, then all smoke should be avoided, he says, “whether it comes from tobacco, marijuana or a forest fire.”

Springer has another lingering concern—“that with legalization [of marijuana] comes a renormalization of smoking.”

Informed counsel & credibility

Physicians need to monitor the cannabis research, sparse though it may be, sources told CVB. And some may need to make a conscious effort to get comfortable discussing cannabis with patients.

It’s a matter of credibility, Lougheed says. “Many patients may feel their physicians are not well informed and able to provide a balanced approach to discussing risks and benefits,” he says. “Once we lose that credibility with patients, they start to look for other sources of information, some of which may not be appropriately vetted.”

Even worse, they may decide not to discuss cannabis use with any of their doctors. But they want to talk about it. After conducting 17 focus groups with Colorado seniors, University of Colorado researchers concluded, “Older adults want more information about cannabis and desire to communicate with their healthcare provider” (Drugs Aging 2019;36[7]:655-66).

“Cardiologists need to create an environment in which patients are willing to talk about cannabis use,” says Kondapalli. In her cardio-oncology practice, she’s accustomed to fielding questions about medical marijuana, which is sometimes used to alleviate cancer pain and the nausea often associated with chemotherapy. “Many of my cancer patients will ask what the risk is, and I tell them: ‘We don’t know exactly.’”

What cardiologists tell their patients likely will evolve as research on cardiovascular effects accumulates. For his part, Shah is urging cardiologists to caution patients against long-term cannabis use. Don’t let patients assume that the lack of research means cannabis use is innocuous, he says. “After all, absence of proof is not always a proof of absence.”

See the related article: Cannabis use disorders double risk of MI after surgery