New Data Underscore Importance of Looking for HCM Before Scheduling TAVR

A 56-year-old man undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) took a sudden turn for the worse during the valve deployment phase of the procedure. He developed dyspnea that progressed to pulmonary edema requiring emergency intervention by surgeons. Intraoperative echocardiography revealed that hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) was the underlying pathology of the decompensation. The patient’s HCM had not been detected on preoperative imaging. After treatment with beta blockers, fluid resuscitation and alpha-1 agonists, the patient stabilized and was released from the hospital. He suffered no lasting complications.

Reported in 2018 by anesthesiologists at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville, the case suggested a message to TAVR operators: “Vigilance and a high degree of suspicion” are critical for avoiding the potentially severe hemodynamic consequences of HCM associated with aortic stenosis, the authors asserted (J Med Case Rep 2018;18;12[1]:372).

Now, a new study is raising the alert even higher for the small number of patients with concurrent HCM and valvular aortic stenosis. This national study of 230 patients (culled from 100,495 TAVRs recorded in the National Inpatient Sample during the 2012-2016 study period) showed markedly worse in-hospital outcomes, including mortality (19 percent), acute kidney injury (23 percent) and postoperative shock (16 percent), compared to those without HCM (JAMA Netw Open 2020;3[2]:e1921669).

Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, N.Y.

“To put the mortality rate of nearly 20 percent of HCM patients into perspective, deaths from TAVR in general are just a couple percent,” says Srihari S. Naidu, MD, senior author of the study, professor of medicine at New York Medical College and director of the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Program at Westchester Medical Center in New York. “This tells us that TAVR centers need to do a much better job of looking for concomitant hypertrophic obstructive physiology and, when it’s detected, remove those patients from the TAVR queue for a further assessment of how bad that physiology really is.”

Another recent study involving patients with severe aortic stenosis and HCM (characterized by a small left ventricular outflow tract [LVOT] due to asymmetric septal hypertrophy) supports Naidu’s recommendation. Published as research correspondence in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, the study found alcohol septal ablation (ASA) may be an effective way to manage asymmetric hypertrophy in patients undergoing TAVR (2019;12[21]:2228-30).

Mount Sinai Health System, New York City

“We found that performing ASA before TAVR can reduce septal thickness and really improve valve deployment and procedure outcomes such as implant depth,” says Gilbert Tang, MD, MSc, MBA, study co-author, associate professor of cardiovascular surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital and surgical director of Mount Sinai Health System’s structural heart program in New York City.

While it can hardly be called a groundswell, some interventionalists are starting to pay attention, according to Naidu. Structural heart disease directors from several leading New York institutions are now routinely referring a growing number of TAVR patients to his HCM Program whenever imaging picks up any signs of subvalvular obstruction.

Challenging diagnosis for physicians

Knowing when and how to recognize HCM can be challenging for physicians. It requires being able to separate out “true HCM”—the genetic form of the disease—from “HCM physiology,” Naidu explains. Both are characterized by asymmetric hypertrophy of the basal septum, which results in a severe narrowing of the left ventricular outflow tract that can become obstructed following aortic valve replacement.

In patients with the genetic HCM variant, asymmetric hypertrophy is often diagnosed early in life through echocardiography and therefore is known to TAVR interventionalists and surgeons. HCM physiology, however, is more subtle. Individuals often are unaware they even have the condition, inasmuch as it can remain masked until identified intraoperatively as the source of an LVOT obstruction during aortic valve replacement.

Naidu recalls a patient about five years ago who had some evidence of asymmetric hypertrophy of the basal septum that devolved into severe LVOT obstruction during TAVR and proved quite difficult to manage. “That raised an eyebrow with us about how we could better invest in these patients,” he recalls. “If you get a severe obstruction afterwards, it can be as bad, if not worse, than the obstruction you had with the valve. It’s hemodynamically worse, accompanied by lower blood pressure and congestive heart failure that are very difficult to treat emergently.”

How, then, should protocols be changed to flag these vulnerabilities before they can do harm? Tang suggests evaluating the septal thickness using transthoracic echocardiography and CT to assess differences in LVOT and annular dimensions to see if the patient is a candidate for ASA prior to TAVR—especially if they have a significant LVOT gradient.

“We would typically rely on the echocardiologist to be part of our heart team to discuss the initial transthoracic findings, and on CT imaging to evaluate aortic root and LVOT anatomy to determine if the patient has HCM that may benefit from preemptive ASA to optimize TAVR outcomes,” Tang explains.

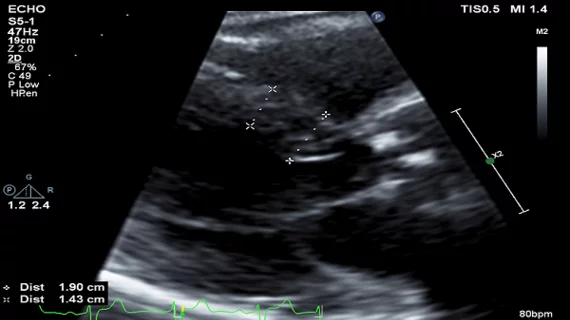

Naidu also points to more comprehensive imaging as the key to enhanced treatment of patients with aortic stenosis and HCM. He explains that under current protocols, echocardiography examines the valve and the size of the aorta, but probably not the subvalvular space, the width of the outflow tract, the thickness of the septum and whether there is turbulence in that area. “We need to look more carefully at the echo to see if there could be obstruction,” he emphasizes. And if that’s inconclusive, he recommends moving on to a transesophageal echo for a more detailed view of the region and advanced hemodynamic evaluation to isolate the two obstructive areas.

Need for TAVR-HCM center alliances

What could help move the needle toward a new awareness of the risks of concurrent aortic stenosis and HCM is the growth in the number of patients undergoing TAVR, and the migration of this increasingly low-risk procedure to younger people. Couple these shifts, too, with the fact that one in every 300 to 500 people is believed to have HCM. As they lead longer lives with the help of defibrillators and other supportive devices, more and more of this population needs aortic valve replacement.

Currently, there are around 40 HCM centers in the U.S. that have achieved advanced certification of their specialized treatment programs through the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Association. They offer a panoply of services for their high-utilization patients, including surgery, interventional cardiology, pediatrics, genetic testing, psychiatric services and dietary counseling. Where HCM centers typically excel is performing ASA and surgical myectomy, procedures designed to reduce the thickening of the interventricular septum and enlarge the ventricular outflow tract.

A critical part of any new protocols for managing HCM/aortic stenosis patients, Naidu believes, must be stronger alliances between HCM centers of excellence and TAVR programs. This, he says, will streamline and promote referral to HCM specialists of patients who might benefit from ASA prior to TAVR.

While many large hospitals already perform ASA and surgical myectomy, Naidu cites a study he led showing that low-volume centers are associated with worse outcomes, including higher mortality, longer length of stay and higher costs (JAMA Cardiol 2016;1[3]:324-32). According to ACCF/AHA guidelines, surgeons, interventionalists and treatment centers should have a cumulative caseload of at least 20 procedures annually and should continue to perform 8 to 10 successful procedures with low complication rates to ensure a prudent level of competence and experience.

“When handled by trained HCM specialists, septal ablation is highly effective,” Naidu stresses. He adds that a potential benefit of preemptive ASA is the ability to forestall from months to years the need for a patient to even proceed with TAVR. The reason is that ASA may improve stroke volume, resulting in more moderate degrees of aortic stenosis and making it a manageable condition. Even if the patient eventually requires aortic valve replacement, it becomes a lower risk procedure without the worry of decompensation.

On the back of recent studies, Naidu is optimistic that the field is ready to focus on the small but very high-risk aortic stenosis/HCM population. “Word is starting to get out that physicians need to take a step back and give the process more thought when something doesn’t look quite right in the subvalvular space,” he says. “They need to think about the possible consequences and outcomes for their patients, and that a little patience up front can avoid regrets later on.”