Succession Planning: Prepare Your Practice to Survive the Retirement Tsunami

With one in four practicing cardiologists over the age of 61, cardiology leaders need to be thinking about how they’ll maintain their workforce and keep their practices producing at optimal levels in the coming decade. “Cardiology practices face a tsunami of retirement,” says Mary Norine Walsh, MD, medical director of heart failure and cardiac transplantation at St. Vincent Heart Center in Indianapolis.

The COVID-19 pandemic is adding to the projected retirement wave as older physicians who might have continued working instead consider winding down their careers rather than risking exposure to a virus to which they could be especially susceptible, according to MedAxiom’s 2020 Cardiovascular Provider Compensation and Production Survey. It’s also possible that the financial hit that most practices took during the COVID-19 shutdowns will spawn retirements, suggests the physician recruiting firm Merritt Hawkins.

Wins all around

Who will replace senior cardiologists as they transition to retirement? Who will step into leadership roles? Succession planning is critical to addressing these and more questions.

“Succession planning is truly essential—and it’s something that historically we haven’t necessarily been good at,” says Marc Newell, MD, chief of clinical cardiology at Minneapolis Heart Institute.

Inadequate or late succession planning may result in inexperienced leaders taking roles they are unprepared to fulfill; practices struggling to keep pace with patient needs; or financial and operational stresses, such as having too many providers in nongrowth areas and not enough in growth areas.

“Without a plan, whoever takes over is really untested—they haven’t had any on-ramping as to what the role requires or been given a chance to develop the leadership skills needed for the role,” Walsh says.

Succession planning is one critical component of the larger task of workforce management, especially given the vast contributions senior cardiologists typically make to successful practices. Investing in a succession plan creates wins for everyone: Senior physicians enjoy smoother paths into retirement; younger doctors can plan their career trajectories; practices maintain quality care delivery and financial health; and patients avoid disruptions that can occur when their cardiologist retires.

Edward T.A. Fry, MD, who chairs St. Vincent Medical Group’s cardiology division and Ascension Health’s CVSL, says succession planning gave his practice the opportunity to think proactively, stave off stagnancy, establish paths for bringing in new people and help junior personnel envision new opportunities. “You need to recognize that change will happen,” he emphasizes, “whether you plan for it or not.”

As CVB talked with cardiology leaders about succession planning, three overarching strategies emerged. In this series, we explore how to build a leadership bench at every level of a practice; why term limits and step-down policies can refresh a practice’s leadership and workforce; and the benefits of establishing a variety of retirement glide-paths.

A unifying theme in CVB’s conversations with practice leaders was that succession planning should not be treated as a one-off, set-it-and-forget-it process; rather, it requires regular reassessment and refinement as conditions both within and outside the practice continue to change.

To build and maintain a strong leadership and workforce, “we constantly assess our needs, strengths and weaknesses,” says David X. Zhao, MD, chief of cardiovascular medicine and executive director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Wake Forest Baptist Health in Winston-Salem, NC.

A solid succession plan builds leadership at every level

Succession planning is about a practice’s top job, but it’s not only about the top job.

Retaining strong managers at all levels is key to smooth leadership transitions, says Lisa C. Murphy, MBA, CPA, who is CAO of the Cardiovascular Institute and the Center for Transplantation & Pulmonary Programs at UC San Diego Health. “We have strong supervisors in each of our areas, which always creates a nice backup plan in case of manager transition,” she says.

Maintaining a strong leadership ladder

Wake Forest Baptist Health maintains a ladder system that reflects three levels of management—top, middle and junior. The personnel at the senior level mentor those at the junior level while those in mid-level positions can replace a top leader who leaves, says Chief of Cardiovascular Medicine David X. Zhao, MD.

“Perhaps they get recruited to someplace else, which is not uncommon, or they get sick or hurt in an accident,” he says. “It’s good to have a plan so that you’re not scrambling.”

A strong ladder also makes it easier to find a successor to lead the practice. After all, most cardiology practices look for leaders within their ranks, notes Edward T.A. Fry, MD, of St. Vincent Medical Group and Ascension Health. Academic practices may go outside of their ranks because they want to go in a different direction, he adds, “but for non-academic practices, it’s crucial for the continuing function of the practice to stay inside the organization.”

Really look for leaders

Associated with the leadership ladder is the crucial task of identifying and mentoring potential leaders for new roles, whether in quality, education or administration, says Mary Norine Walsh, MD, of St.

Vincent Heart Center. The identification process should be transparent, including a call for applications and a search committee.

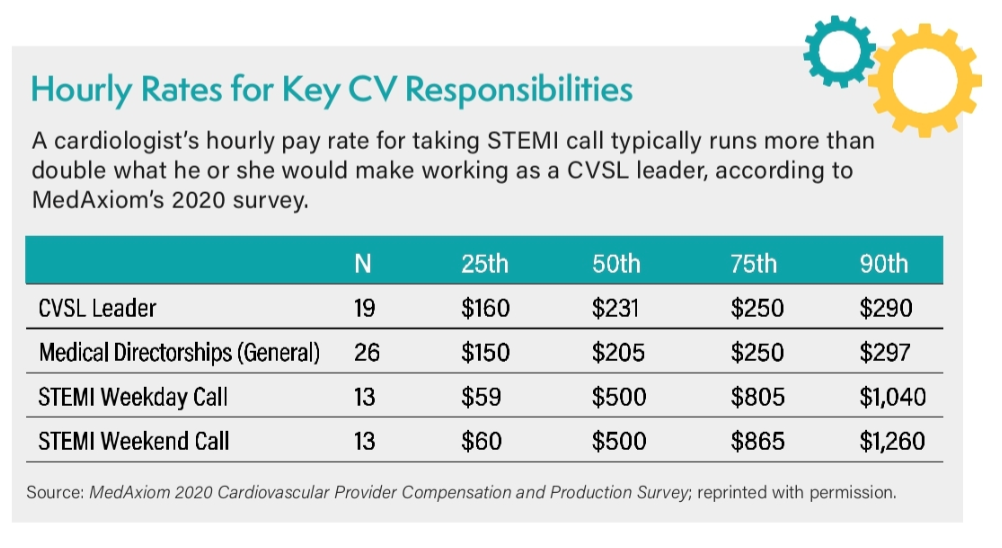

Finding potential leaders can be challenging, sources told CVB. Early-career physicians typically don’t have the experience and exposure to deal with thorny issues, especially those related to personality and conflict management, Fry says. In contrast, mid-career cardiologists may be reluctant to commit to leadership roles because they are in their peak earning years, he says. MedAxiom data underscore Fry’s point, revealing the significant pay gap between taking STEMI call vs. serving as a CVSL leader (see figure on page 10).

“The pool is smaller than you might think,” Fry adds. His practice makes a point of publicly asking its cardiologists who have been in practice for seven or more years if they would be interested in a leadership position.

Developing new leaders also takes time and effort. To be successful, Walsh says, most need a combination of experience, institutional knowledge and relationships they’ve built over time.

Recruit Wisely

Recruit Wisely

Organizations should use recruitment to help fill gaps in their management ladders, Zhao says. Too often, organizations only recruit when they are “in a pinch and need coverage,” he explains.

If a practice plans well, newly recruited cardiologists should be ready to take over coverage whether a senior cardiologist gives up call duty or just goes on vacation, Zhao says. Most see it as an opportunity and are eager to step up, he adds. “What you don’t want is a situation where people are already stretched, and then suddenly someone is not taking call anymore. That’s where the conflicts arise.”