Merger mania: What will the new world of healthcare delivery mean for cardiology?

The entry of new players and dozens of potentially disruptive mergers and acquisitions are pushing healthcare in nontraditional directions, yielding opportunities for cardiologists to help shape the transformation.

As the traditional boundaries between providers, insurers and pharmacies become ever more blurred, the future of healthcare delivery in this country is coming into sharper focus. The pending merger of national pharmacy chain CVS with giant healthcare insurer Aetna. The entry of Amazon/Berkshire Hathaway/JPMorgan Chase into the turbulent healthcare space. The relentless consolidation of hospitals and physician groups. The groundswell movement toward value- and outcomes-based care. All of these trend lines point to a vertically integrated future where healthcare is delivered in a host of nontraditional ways—with enormous implications for every patient and provider, including cardiologists.

“We’re going to see healthcare pushed closer to consumers through retail settings that make it easier for them to access,” says Aaron Martin, executive vice president and chief digital officer of Providence St. Joseph Health, a not-for-profit health system of 50 hospitals and 829 clinics born nearly two years ago through the merger of two large healthcare organizations. As for cardiology, he envisions substantial change as telehealth and remote monitoring via an emerging generation of digital devices reconfigure how patients and physicians interface, resulting, for example, in fewer in-office visits and the ability to uncover potential problems before they morph into major ones requiring hospital care.

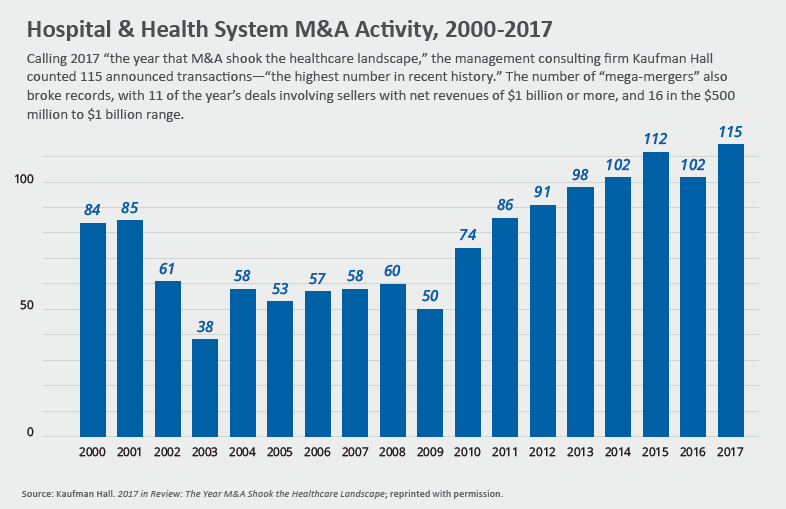

More than ever, the focus across healthcare will be on gaining scale through mergers and acquisitions. According to Healthcare Finance News, there were more than 50 such pairings of significance in 2017, and the pace shows no signs of slowing. While the federal government has blocked a number of large deals between healthcare insurers, nontraditional vertical integrations between third-party payers and provider organizations—often at odds with one another—have been gaining currency.

“The question is, how do you cut through the inefficiencies of the current system, which I call medical waste, in order to reduce cost?” asks Tony Farah, MD, chief medical and clinical transformation officer for Highmark Health, the byproduct of a vertical merger nearly five years ago between West Penn Allegheny Health System and insurance mainstay Highmark. “What’s really required is disruption—but it has to be good disruption.”

CVS and Aetna are convinced they can provide that kind of upheaval by joining CVS’s vast network of 10,000 retail pharmacies with Aetna’s sizeable analytics and data resources. The goal: to forge a new model of community-based health hubs offering individuals access to a wide range of medical care and counsel.

The $69 billion merger has the power to “alter the consumer experience with respect to how healthcare is delivered,” emphasizes Dan Mendelson, president of Avalere, a Washington D.C.–based healthcare consulting firm. And analytics, he adds, could well be the engine that drives this new enterprise. “The potential here is huge for identifying patients who need therapies, for delivering better care to patients and for insuring compliance with medications,” he explains. “Analytics will tend to shift healthcare out of the hospital, because it’s an expensive site of care.”

That transition is well under way. In a recent New York Times op-ed, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, vice provost at the University of Pennsylvania, pointed out that hospital admissions per 1,000 Americans have decreased by more than 10 percent since 1981 as the population was increasing by 40 percent. Over the same period, the number of hospitals declined from 6,933 to 5,534. Emanuel argued that visiting nurses could give patients with heart failure, pneumonia and some serious infections hospital-level treatments at home and it would “usually lead to more rapid recoveries, at a lower cost” (online Feb. 28, 2018).

Healthcare bows to a retail model

How the retail/home model might actually work can be gleaned from the experience of Providence St. Joseph Health, whose 111,000 caregivers serve seven states, from California to Alaska. The health and social services system has rolled out a primary care service for same-day treatment of low-acuity health problems known as Express Care that’s embedded in 25 Walgreens pharmacies and eight standalone clinics in Seattle and Portland.

Express Care empowers patients through its integrated digital platform to choose their point of care: at a neighborhood pharmacy or clinic where they can see a clinician either in person or remotely via an audio/visual-equipped device, or in their own home. Through an online scheduling app that looks a lot like OpenTable for restaurant reservations, consumers make their choice. This includes, according to Martin, the Express Care at Home app to set up a house call from a Providence St. Joseph provider in the event they can’t easily get to one of the plan’s clinics for a non–life-threatening problem.

The success of the system is underscored by the fact that instead of a 5 percent online scheduling rate, typical of primary care practices with such a capability, Express Care tallied 50 percent and, instead of a limited number of telehealth “visits,” the system recorded nearly 10,000 last year.

Just as important, says Martin, who previously managed Amazon’s self-publishing and print-on-demand business, is that the program’s integrated digital platform enables every interaction, regardless of venue, to become part of the patient’s electronic medical record (EMR), where it can be reviewed by his or her primary care physician to help maintain a continuum of care.

How would cardiology be affected by this electronically powered system? Martin says he’s been informed by cardiologists in the Providence St. Joseph provider network that patients who have undergone procedures such as stenting and are now trending in the right direction may not really require a traditional in-office visit. “And that makes a lot of sense,” he says, “especially in some of our markets like Texas, Alaska and Montana, where patients far removed from a doctor’s office could more effectively receive a checkup through telehealth.”

Highmark Health also has become a laboratory for change following its integration of care delivery and care financing functions—and cardiologists are playing a pivotal role in the transformation. Specifically, they’re involved, along with other physicians, in creating new clinical pathways for care of patients with heart failure and other serious conditions, which in turn will lead to new payment models for services that match outcomes with the most cost-effective way of achieving them.

Farah, an interventional cardiologist, says this exercise goes well beyond existing clinical practice guidelines. “Patients are nowadays concerned with the entire transition of care, whether they’re coming into the hospital or leaving the hospital and getting home care,” he explains. “So, we’re starting to embed those pathways into our postacute care platform. We want to incentivize providers to do the right thing for patients.”

Creating a seamless pathway for care

Highmark Health has put that concept into practice through a pilot program called Enhanced Community Care Management (ECCM), which delivers multidisciplinary team-based care to patients in physicians’ offices, in the hospital or at home. What differentiates this initiative, though, are ECCM’s nurse care managers, who work closely with patients to achieve meaningful behavioral change and self-management techniques. The overriding goal is to drive cost savings through declines in emergency room visits, inpatient admissions and overall medical and pharmacy spending.

In the first year of the EECM program—in partnership with Allegheny Health Network—cost savings per month for each enrolled member were 21 percent. What’s more, for each member served, ECCM has avoided one hospital admittance through the first year and approximately $10,000 of costs.

Among the changes that Mendelson sees for cardiology in the unsettled period ahead are growing numbers of specialists operating in larger groups and more alignment with either health systems or insurance companies that own health systems.

“Very good cardiology groups are feeling pressure to combine into larger groups or to seek a different economic model,” Mendelson notes. And he indicates that model will undoubtedly include reliance on quality measures as a payment mechanism. “We now have Medicare Advantage paying healthcare plans more if population cholesterol levels are low, and that’s the kind of thing that will drive interest in cardiovascular care by those plans,” he says.

Regardless of the industry’s direction, it’s clear that technology will increasingly be in the driver’s seat, which is why Amazon’s recent entry into the field (along with its high-profile partners) is creating such anticipatory buzz. The new players have indicated they will use their digital strength to simplify healthcare, though how they will accomplish this and bring down ever-growing costs is still a big unknown.

“They’ve been very successful in disrupting more than one space,” says Farah, about Amazon. But, he acknowledges “the burning platform is there for many of us, and that’s what is going to lead to healthy disruption.”