Reducing CIED Infections and the Cost of Care: Lessons from Cleveland Clinic

Thinking has changed: Cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) infections are a bigger deal than we thought.

The latest research supports a new approach to who and how we treat, says veteran cardiologist Bruce Wilkoff, MD, the director of cardiac pacing and tachyarrhythmia devices at Cleveland Clinic. In fact, he thinks it’s time for electrophysiologists (EPs), cardiologists, nephrologists, infectious disease specialists, primary care physicians (PCPs) and healthcare system leaders to modify their best practices to spot and reduce infections, extend and improve quality of life for patients and proactively reduce cost of care for healthcare systems.

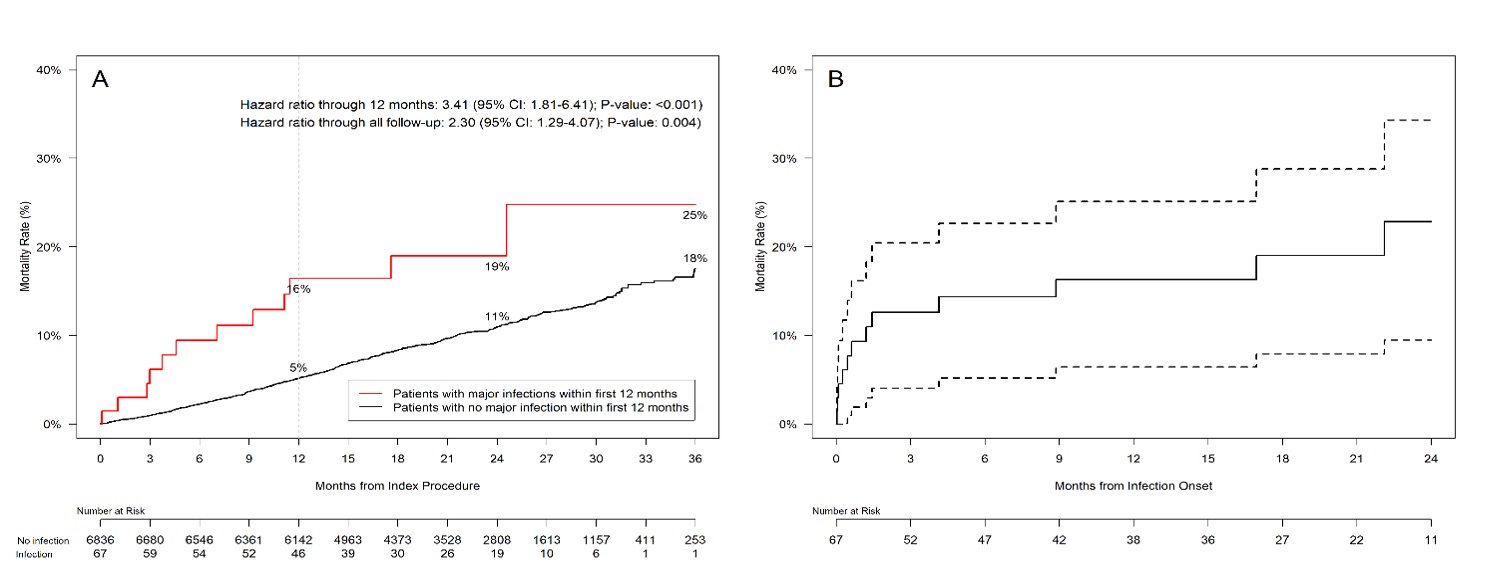

Approximately 1.5 million patients receive a CIED each year, and a vast majority of those procedures are a resounding success.[1] Infections, however, remain a significant complication that affect 1 to 2% of patients overall, and the mortality rate after an infection is more than 25%;[2] an increased risk of three-fold compared to patients who do not develop an infection.[3]

So, what can be done to limit CIED infections? Wilkoff has dedicated much of his career to answering that question.

“CIED therapy is phenomenal,” he says. “It changes lives. It’s an amazingly effective therapy. But sometimes something goes wrong, and we need to be able to act when that happens.”

Wilkoff says he has always been passionate about implantable devices since implanting his first in 1985. That passion got personal in 1988 when his father developed an infection after receiving a pacemaker. Doctors knew little about infections at that point in time, he notes, but his father was treated by one of the world’s few experts and did well.

“Very little was being done back then when it came to lead extraction,” he explains. “There was no real process in place for managing these patients, and removals had to be done using fairly primitive tools. That’s when I started focusing more and more on lead extraction with some colleagues of mine. We didn’t even realize at the time just how common this issue was—we just knew it was a patient group that really needed some help.”

Since then, Wilkoff has logged more than 10,000 CIED procedures and close to 4,000 lead extractions. Because of his role at Cleveland Clinic, he often treats high-risk patients who present with especially challenging cases. He’s also one of the world’s most prominent voices on lead extraction policies, working on the development of protocols and guidelines.

A closer look at CIED infections

CIED infections typically manifest in about half the patients as a local occurrence where the device was implanted, with significant damage to the patient’s skin, and as a systemic infection accompanied by endocarditis, vegetations, high fever and positive blood cultures. Often there is evidence of both local and systemic infection. Wilkoff notes that over three-quarters of infections occur after the placement or replacement of the pacemaker or ICD. The most obvious infections occur within three months of CIED placement, but only half of the infections manifest during the first year after implant. The remainder show up over the next 2 to 3 years.

Some infections, much fewer, are not related to a CIED surgery but to an infection the patient has in another part of his body, either from an abscess, a blood stream infection, a bone infection or a valve infection. Sometimes it isn’t clear where the infection started, but the treatment is the same, extraction of the CIED system and antibiotics.

And while some infections are obvious to diagnose, there’s often a long delay between the time of the infection and when it first becomes clinically apparent. That delay, Wilkoff explains, can make diagnosing a CIED infection particularly challenging.

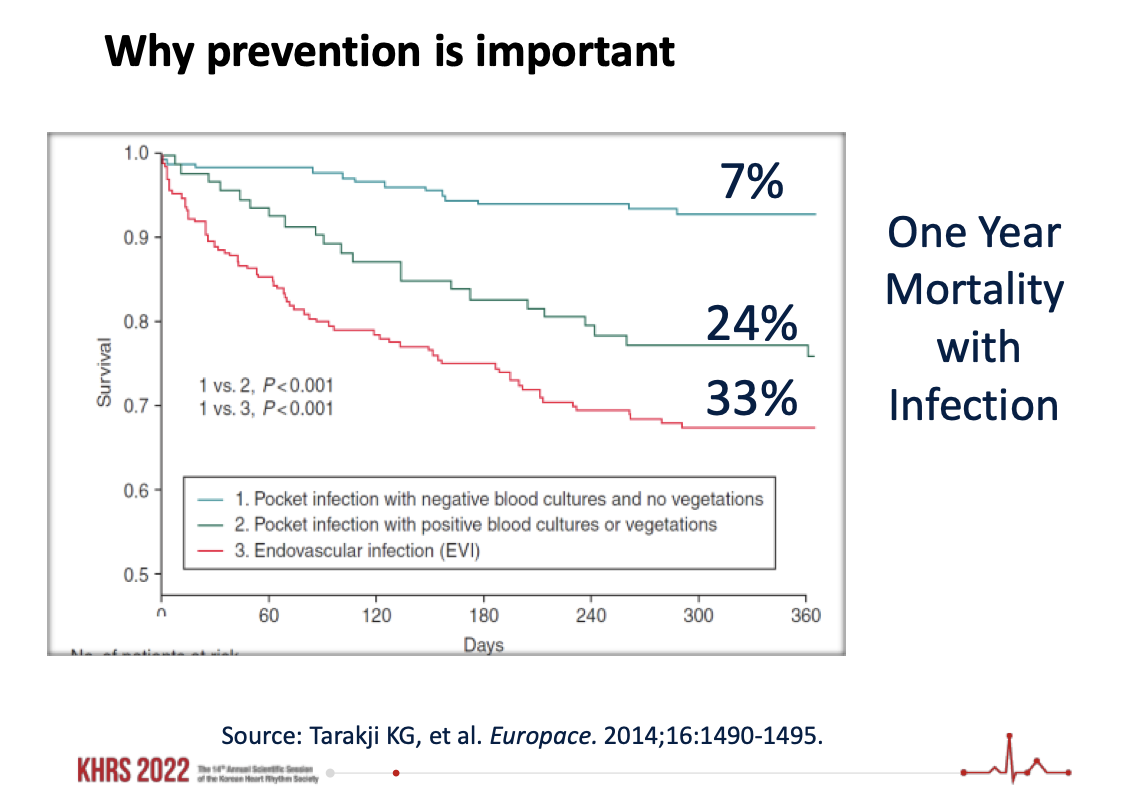

“It’s a big deal when you remember that when you treat a CIED infection properly, you still face a one-year mortality rate of at least 25%. And if you don’t treat it properly, you’re facing a mortality rate as high as 90%.”

- Bruce Wilkoff, MD, Director of Cardiac Pacing and Tachyarrhythmia Devices, Cleveland Clinic

“Even if the issue presents as swelling or a device that is literally pushing through the skin, many people just don’t tie it back to a CIED operation that happened months—or even years—in the past,” he says. “But that’s when most occur.”

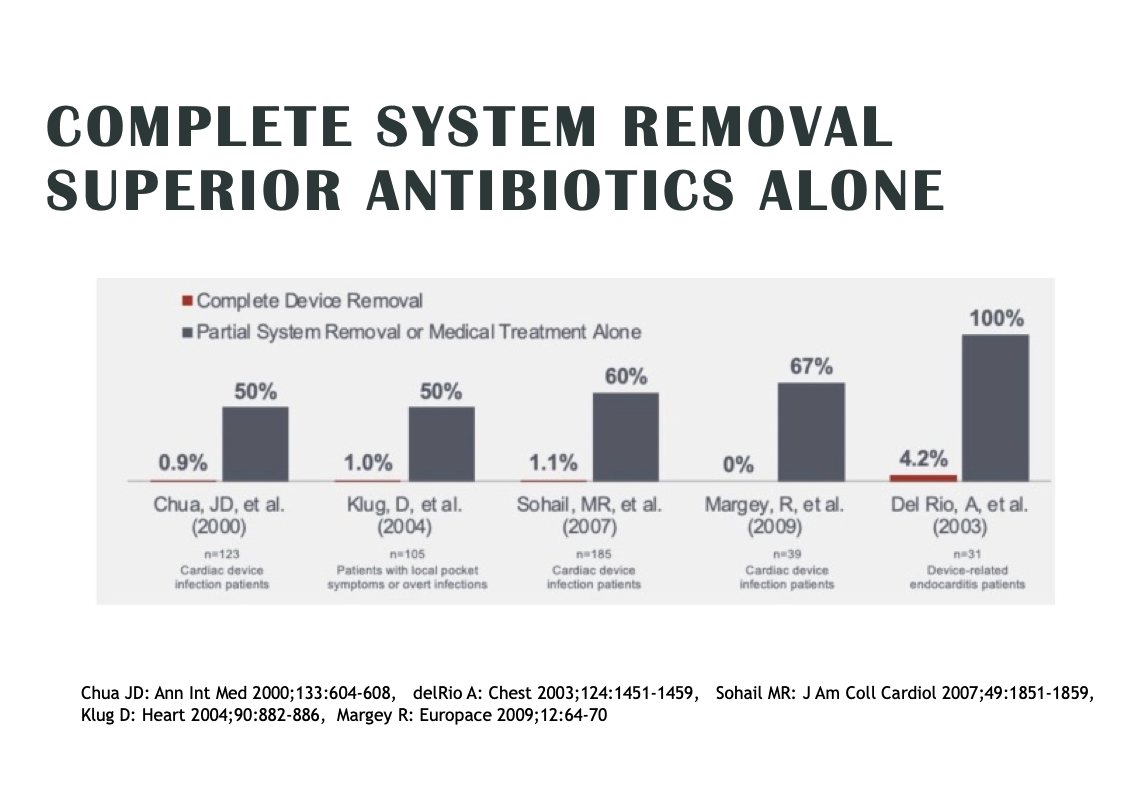

Most CIED infections are almost impossible to cure without removing the device and leads altogether. Antibiotics can help to a certain degree, but the bacteria causing the infection is often surrounded by a protective biofilm that protects against both antibiotics and the patient’s own white blood cells.

“Antibiotics for a CIED infection are sort of an ostrich move,” Wilkoff says. “Even among physicians there’s this perception that infections are curable with antibiotics. It just isn’t always true. Extraction is the proven method. And the scary part is once bacteria is in the bloodstream or pocket, they’re very hard for the body to fight off. It’s a big deal when you remember that even when you treat a CIED systemic infection properly, you still face a one-year mortality rate of at least 25%. And if you don’t treat it properly, you’re facing a mortality rate as high as 90%."[4]

A few years ago, a more innovative tool emerged to stop these infections before they begin.

Absorbable antibacterial envelope hits the scene

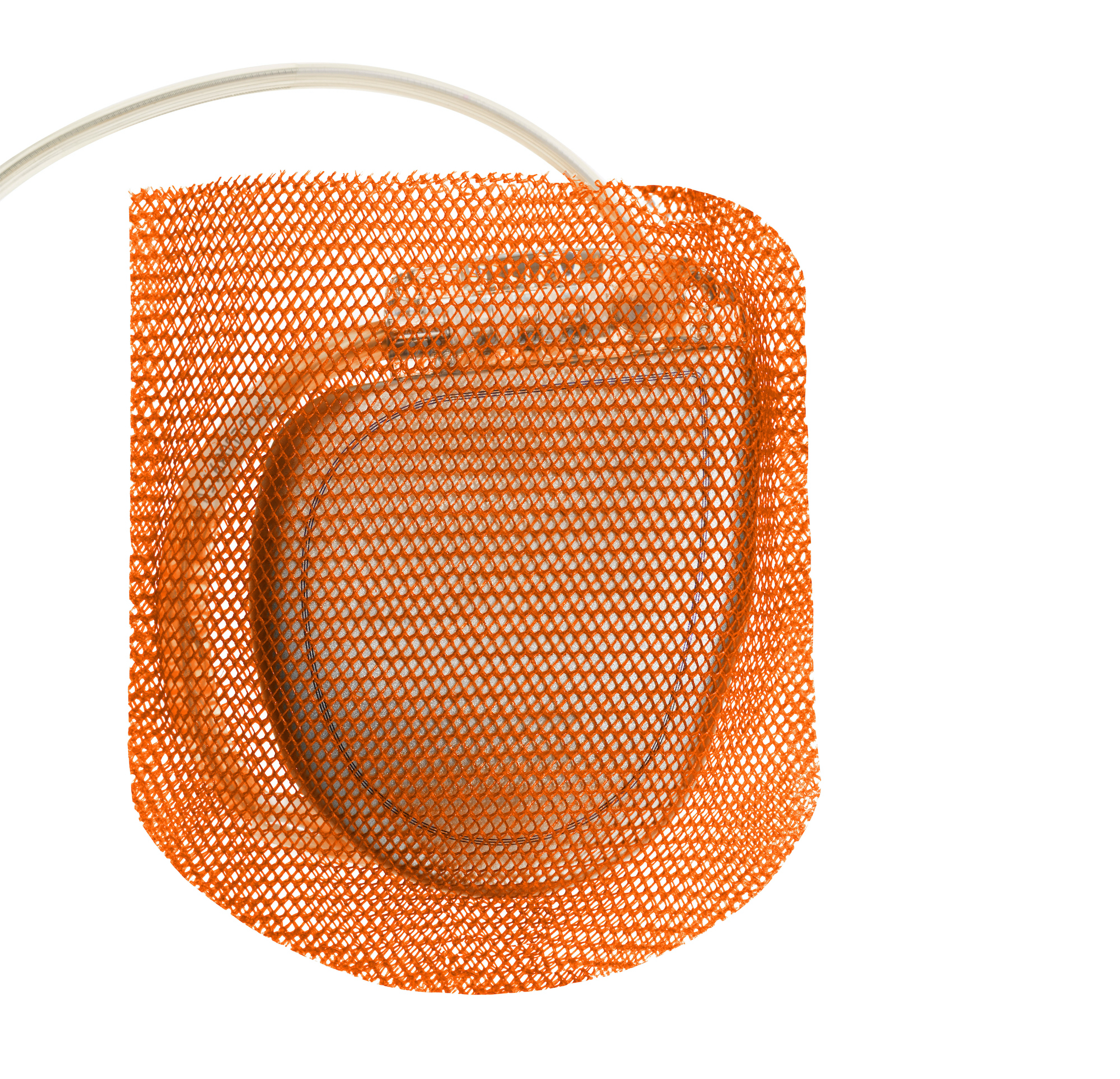

A small healthcare technology company out of New Jersey first caught Wilkoff’s attention more than a decade ago. TYRX was in the process of developing an implantable, drug-eluting envelope technology capable of protecting a CIED from infection when it was implanted into a patient. The envelopes, which worked by eluting antibiotics over a minimum of seven days and then resorbing within a few months, were still under development at the time. Wilkoff was a skeptic based on prior disappointments in similar technologies but formed a close connection with the company hoping this new solution could be a potential breakthrough for physicians and patients alike. While an early, non-absorbable version of the envelope gained FDA clearance in 2008, the absorbable version used today gained FDA clearance in 2013.

After Medtronic acquired TYRX a year later, the company launched the largest global CIED trial to date to assess the capabilities of the envelope’s ability to prevent infections. The World-wide Randomized Antibiotic Envelope Infection Prevention Trial (WRAP-IT) was designed to evaluate the envelope’s ability to reduce CIED infections one year after device replacement, upgrade, revision or de novo cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D) implants.[5] Wilkoff played a key role on the trial’s steering committee.

The results were compelling. The WRAP-IT study, presented in March 2019 at the American College of Cardiology annual meeting and published in The New England Journal of Medicine, found that the absorbable antibacterial envelope reduced major CIED infections by 40% and pocket infections by 61%. In addition, it found that envelopes did not increase the risk of procedure-related complications compared to standard care.

The patient base of nearly 7,000, with a mean age of 70.1 years, included those undergoing CIED generator replacement or system upgrade with or without new leads, as well as de novo CRT defibrillator implantation. Effects of the envelope in reducing infections were consistent across patient sub-groups and out to 3 years follow-up.

According to a secondary clinical and economic analysis published in Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, CIED infections were associated with a greater than 3-fold increase in all-cause mortality, a reduction in quality of life for 6 months, and a disruption in CIED therapy in 36% of patients.[3] The cost per patient of a CIED infection in the U.S. was estimated at $55,000 for the hospital, and assuming Medicare fee-for-service or Medicare Advantage: $26,000 for the payer and $2,100 for the patient, or $57,000 to the payer and $1,500 to the patient, respectively.

“Management of patients with a CIED involves more than the implantation, meaning there are follow-up procedures for upgrades, battery or lead changes,” Wilkoff says. “And every time the CIED pocket is revisited, there is that risk of infection. The envelope works to cut that risk very significantly.”

The envelope also had a large impact in another key area: the risk of CIED infections among patients with hematomas was reduced by 82%.

“When patients develop a hematoma, it’s an extraordinary multiplier of their risk of infection being 11 times higher,” Wilkoff says. “And it’s not just big hematomas that are a problem—even the little ones can lead to a much higher infection rate for these patients. When we used an envelope, we brought the infection rate back down to a normal rate, which makes the cost effectiveness of this much better. And we found that these patients who developed hematomas were often those on anticoagulation and antiplatelets, or both. These patients benefit from the envelope.”

Considering the costs

“It is important to get out of the mindset of just focusing on the cost of the initial implant; what we need to be focusing on is the full cost of the treating the patient. If you just look at the cost of that CIED procedure, adding something like an antibacterial envelope is never going to make financial sense, because the infections are not an issue right away. If you broaden your perspective, however, and look at the cost of treatment over many months, you can gain a better understanding of how cost-effective it is to reduce the frequency of these infections.”

- Bruce Wilkoff, MD, Director of Cardiac Pacing and Tachyarrhythmia Devices, Cleveland Clinic

With the clinical benefits proven, Wilkoff and colleagues dug into the economics. In a separate cost-effectiveness analysis of the WRAP-IT data published in September 2020 in Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, the cost-effectiveness ratio of the envelopes was found to be much lower than the study’s upper willingness-to-pay threshold of $150,000.[6]

“It’s very clear this is cost-effective,” Wilkoff says. “It’s important to get out of the mindset of just focusing on the cost of the initial implant; what we need to focus on is the full cost of the treating the patient. If you just look at the cost of that CIED procedure, adding something like an antibacterial envelope is never going to make financial sense because infections are not an issue right away. If you broaden your perspective and look at the cost of treatment over many months, you can gain a better understanding of how cost-effective it is to reduce the frequency of these infections.”

Wilkoff also notes that solution becomes even more cost-effective when physicians are treating high-risk patients or providing care in surgical and procedure rooms without the sterility standards available in most U.S. facilities.

Looking across the world, the long-term risk of a CIED infection also varies considerably from one study and country to the next. While the WRAP-IT team estimated the infection rate to be 1.2%, many high-risk patients were excluded from that analysis, which likely brought the infection rate down. A recent analysis of Danish data found the CIED infection rate among certain patient populations could be as high as 6.76%.[7] Higher infection rates mean that solutions combatting those infections are even more cost-effective than they may originally appear.

“I think we underestimated the cost effectiveness in the trial, because in the real world [with all-comers] the infection rates are higher than what we estimated,” Wilkoff says. “At 6.76%, every single patient should absolutely be getting an envelope. Reducing the infection rate by 50% would make a huge impact not only on the individual patient and their morbidity and mortality, but an economic decision that strategically, on a public policy type of basis, really should be done.”

The ongoing evolution of patient care

Back at Cleveland Clinic, all high-risk patients undergoing a CIED procedure are treated with an absorbable antibacterial envelope. This includes all replacement or upgrade procedures and anytime the pocket is reopened. It also includes patients at increased risk of infection because of immunosuppression or hematomas.

“So like in WRAP-IT, at least 40% of procedures are replacements and upgrades,” Wilkoff says. But since the majority of his cases include complex lead extractions, he opts for the antibacterial envelope in closer to 70 or 80% of patients.

“Our patients need CIED therapy to live,” Wilkoff says. “What we need to do is make those procedures as safe as possible. This strategy works more than any other strategy I’ve seen”

The antibacterial envelope is gaining popularity around the world as well. In 2020, a consensus statement published by the European Heart Rhythm Association and endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society, Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, Latin American Heart Rhythm Society, International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases and European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases gave the use of antibiotic envelopes for high-risk patients its highest recommendation.[8]

Despite the guidelines, we’re falling short on treating high-risk patients. Some 4 out of 5 patients are not being treated according to HRS/EHRA Class I consensus recommendations and guidelines for CIED infection that includes full system extraction.

That’s according to a U.S.-based analysis of CIED infection care released in April at the American College of Cardiology annual meeting. In the CIED Infection Medicare Study, Duke researchers found that in the absence of guideline-driven care, the risk of death after a CIED infection is 32.4%.[9] Complete hardware extraction within 6 days was associated with a 42.9% lower risk of death compared with patients who did not undergo extraction.

The study analyzed a Medicare fee-for-service population over 14 years, examining more than 1 million patients who received a CIED between Jan. 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2019. Patients included in the CIED infection group were those with an implant greater than 12 months old, had a primary diagnosis for infection of a device implant, and had documented antibiotic therapy.

“This is more data showing what we’ve learned: that treating infections by extracting leads improves patient survival rates significantly,” Wilkoff notes. “And these numbers show just how big of a deal this is. The earlier you treat, the better the outcomes. Definitive therapy and removing the device and leads, not just treating with antibiotics, is the way to reduce the mortality toll. The value of the envelope keeps multiplying the more risk factors there are and more complex the patient—particularly those at risk of having hematomas.”

Improving infection awareness

As health systems work to limit CIED infections with advanced technology, Wilkoff says the next step in prevention is improved awareness.

“We need to identify these infections as quickly as possible, and a big part of that has to do with patients paying attention to their bodies,” he explains. “Look how helpful self-exams have been when it comes to fighting breast cancer and skin cancer. Patients who undergo these CIED procedures need to examine the pocket from time to time and think about any symptoms they may be experiencing. If they notice something, they need to reach out to their doctor right away to get it checked out.”

Hematoma prevention, he says, stands out as another area that should be top of mind for physicians due to its direct impact on infection mortality. He also sees an opportunity for providers to work more closely with one another. Not all patients will return to their EP, he says, and many end up in an emergency clinic or their PCP’s office. If health systems can become better prepared to combat infections, it’s going to make a crucial difference in the lives of millions of patients.

“My personal passion is about moving device therapy towards a zero morbidity profile,” Wilkoff says. “Zero infections should be our goal. I can't prove why people get infections, but I can prove that the strategy we use reduces net manifest infections, mortality, including extractions and cost. We improve quality of life.”

And looking back, Wilkoff can’t help but think about his father’s pacemaker infection in 1988.

“Back then, physicians didn’t have these tools or these data,” he says. “They didn’t even fully understand what CIED infections looked like. He was lucky. He did well. Now, we have these standards, we have the data, we have a healthy community that is focused on bringing about change. We look out for our patients while also being responsible to our healthcare systems in reducing the cost to care for them. It’s just really gratifying.”

References:

- Mond HG, Proclemer A. The 11th world survey of cardiac pacing and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: calendar year 2009 — a World Society of Arrhythmia’s project. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011;34:1013-1027.

- Goette A, Sommer P. Infections of cardiac implantable electronic devices: still a cause of high mortality. EP Europace, Volume 23, Issue Supplement_4, June 2021, Pages iv1–iv2.

- Wilkoff B, Boriani G, Mittal S. Impact of Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Infection. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020 April; 13:e008280.

- See charts at bottom as sources to explain possible CIED post-infection mortality rate as high as 90%.

- Tarakji K, Mittal S, Kennergren C. Antibacterial Envelope to Prevent Cardiac Implantable Device Infection. N Engl J Med 2019; 380:1895-1905.

- Wilkoff B, Boriani G, Mittal S. Cost-Effectiveness of an Antibacterial Envelope for Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Infection Prevention in the US Healthcare System From the WRAP-IT Trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020 Oct;13(10):e008503.

- Olsen T, Jorgensen OD, Nielsen J C. Incidence of device-related infection in 97 750 patients: clinical data from the complete Danish device-cohort (1982-2018). Eur Heart J. 2019 Jun 14;40(23):1862-1869.

- Blomström-Lundqvist, C., et al. (2020, Jun 1). European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) international consensus document on how to prevent, diagnose, and treat cardiac implantable electronic device infections-endorsed by HRS, APHRS, LAHRS, ISCVID, ESCMID in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J, 41(21), 2012-2032.

- Pokorney SD. Low Rates Of Guideline Directed Care Associated With Higher Mortality In Patients With Infections Of Pacemakers And Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators. American College of Cardiology (ACC) Late Breaking Clinical Trials. Washington, DC, USA April 2022 [presentation].