Covenants & Consequences: Is Your Noncompete Set to Blow Up Your Career Plans?

It’s the signature that could derail even the best-laid career plans.

It’s the signature that could derail even the best-laid career plans.

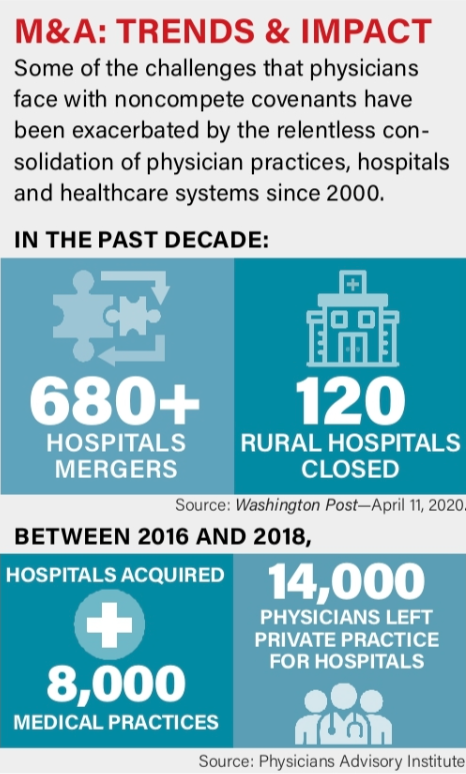

Too often physicians sign contracts with a new hospital or healthcare system without thinking through the longer-term consequences of the noncompete clause. Truth is, these covenants can turn out to be figurative time bombs, ready to blow up later, when physicians decide to end their employment. Suddenly, they find themselves barred from taking a new job without moving miles, counties or even states away from their professional base to avoid violating the terms of the agreement.

“Lots of doctors are getting caught up in these clauses nationally,” says one cardiologist who feels he was forced to give up his patients when his contract with a large hospital system expired and he wanted to move on. “They’ve become a way to trap doctors—almost enslave them—into staying with one system.”

This cardiologist is one of several who have reached out to CVB about noncompete covenants in recent years. “Write a story about the risks that come with noncompetes,” they urged. To protect them from possible ramifications with past or current employers and encourage candor, we agreed to honor their requests for anonymity.

Finding Middle Ground

It Might Be Measured in Miles or Months

Of course, there are arguments to be made on both sides of noncompete covenants, which are designed to prevent a physician from practicing within a certain geographic area around the employer for a prescribed time period if the doctor decides to pull up stakes at the end of his or her contract.

On the *pro* side, noncompetes are written in a way to protect the legitimate business interests of the employer, be it a hospital, healthcare system or private practice that hires physicians. Because that entity typically pours money and resources into building the practices of physicians and groups, it is obviously not keen on seeing them leave and resurface at a nearby hospital or office, poaching patients and revenue in the process.

“I understand the need to protect that investment,” acknowledges a cardiologist who became ensnared in a career-altering noncompete, “but at the same time there has to be some fair middle ground that protects physicians and their patients.”

“I understand the need to protect that investment,” acknowledges a cardiologist who became ensnared in a career-altering noncompete, “but at the same time there has to be some fair middle ground that protects physicians and their patients.”

Which gets to the *con* side of the noncompete. The zones within which physicians agree to not compete are usually measured in miles from the employer’s site. Determining a reasonable and fair distance can put the physician at a severe disadvantage, especially in urban areas. In a city like Chicago, for example, a 10-mile radius puts a sizable chunk of business off limits, while the same distance in a rural area may be meaningless. Even greater dangers lurk when a hospital opens satellite offices and clinical practices—each of which could have its own noncompete radius—that push the restricted territory to multiple times what the physician had originally envisioned. And that could extend even farther when new hospitals or health systems are acquired.

“We became victims of our own success,” asserts one member of a cardiology practice bought up by a hospital whose noncompete covered a wide radius for more than 18 months if the contract ended. The hospital continued to grow outward, thanks in large part to the reputation and efforts of its cardiology partner, multiplying the area in which the practice and its physicians were no longer able to contractually serve when, at the end of the agreement, they decided to depart.

“The ones hurt the most were not the doctors and not the hospital, which lost a bit of income,” the cardiologist says. “It was the patients, many of them elderly, who depended on us for their care and now had to suddenly find other providers. Unless, of course, they didn’t mind driving very long distances to continue to see us.”

Geography Matters

Enforceability, Reasonableness & Other Matters of State

The enforceability of noncompete clauses varies widely from state to state and often depends on the circumstances of each case and a rather vague standard of reasonableness.

Joel Porter, a healthcare attorney in Birmingham, AL, with Maynard Cooper & Gale, P.C., explains: “Most states allow some sort of noncompete against professionals, but in some they’re only enforceable within certain parameters outlined in a statute. In other states, the clauses are more open-ended and hold that you must have a reasonable noncompete geographic area within a reasonable period of time to be enforceable.”

Noncompete covenants often are looked upon unfavorably by the courts when they’re too strictly written and perceived as a restraint of trade or when they might prevent a physician from earning a living and supporting a family. Generally speaking, restrictive timeframes of more than two years are likely to strain the definition of “reasonable” in the eyes of the legal system.

“Most states allow some sort of noncompete against professionals, but in some they’re only enforceable within certain parameters outlined in a statute.” Joel Porter Maynard Cooper & Gale, P.C., Birmingham, AL

A number of states—for example, Colorado, Delaware, Massachusetts and Rhode Island—have taken statutory action to prohibit or severely curb the use of noncompete clauses. Florida, for one, enacted in 2019 a law that prohibits restrictive covenant agreements (and voids existing ones) in cases where all physicians in a “medical specialty” within a county are employed by the same healthcare entity or its affiliates.

N egotiation Room

egotiation Room

Consider Professionalism, Precedents & Pathways

Even though healthcare employers hold many of the cards when negotiating contracts with new providers, cardiologists are far from powerless. Established practices have more leverage in pressing for flexible language that limits how long the noncompete will remain in force, the restrictive radius and how many locations or satellites within the healthcare system (if any) carry their own constraints on physician activity.

Porter says it’s possible to write employment agreement terms that essentially unwind the contract if a hospital undergoes a major change, such as a consolidation or buyout, and the cardiology group no longer wishes to remain.

Another exit pathway is a *buyout* of the clause, or some portion of it, by the physician or the next employer. Some states require that a buyout mechanism be part of the professional contract; others allow it even if it’s not built in. One cardiologist who spoke to *CVB* off the record was able to negotiate upon departure a considerable reduction in a large buyout by agreeing to stay on the job for an extra few months and help find a replacement with comparable skills.

“What made this possible was the good relationship I had maintained with the hospital,” he explains. “Even though I had some grievances, I was never antagonistic with them, and that approach set the stage for us to reach a solution that benefited everyone.”

How flexible are hospitals when it comes to negotiating terms of standard noncompete covenants?

“Hospitals are not typically inclined to let physicians out of noncompetes when they’re leaving because it sets a bad precedent for them,” says Minneapolis Heart Institute (MHI) President William Katsiyiannis, MD, who has been on both sides of the noncompete fence as a cardiologist and currently as a healthcare executive. “While the negotiating power of the physician is really reduced, he or she may be able to use the noncompete as leverage to obtain something else that’s favorable. For example, in exchange for the noncompete clause, they might be able to negotiate a different compensation or benefits package.”

“Hospitals are not typically inclined to let physicians out of noncompetes when they’re leaving because it sets a bad precedent for them,” says Minneapolis Heart Institute (MHI) President William Katsiyiannis, MD, who has been on both sides of the noncompete fence as a cardiologist and currently as a healthcare executive. “While the negotiating power of the physician is really reduced, he or she may be able to use the noncompete as leverage to obtain something else that’s favorable. For example, in exchange for the noncompete clause, they might be able to negotiate a different compensation or benefits package.”

MHI maintains a seven-county noncompete zone that surrounds its approximately 40 practice sites—a swath that Katsiyiannis concedes would require departing providers to either physically move from the area or do a lot of traveling while the noncompete is still in force.

Katsiyiannis believes, however, that noncompete clauses have diminished in importance and value to either side over the past 10 years as more physicians have become employed by healthcare systems. Fact is, it’s extremely difficult for a physician to separate patients from a hospital network with multiple specialists, including primary care doctors.

Aiming for Equal Risk

Turn Down the Burn for All Parties

Before joining a health system, physicians and groups need to know the precise terms of what they’re signing, and they need to carefully consider the applicable restrictions to their ability to practice later if they decide the partnership is not working.

“I advise everyone joining our system to have a lawyer look at the contract so that they fully understand all its terms,” stresses Katsiyiannis.

“While the negotiating power of the physician is really reduced, they may be able to use the noncompete as leverage to obtain something else that’s favorable.” William Katsiyiannis, MD, Minneapolis Heart Institute

Among those considered most vulnerable to the vagaries of noncompetes are young physicians taking their first job. Often, they are less attuned than seasoned physicians to the consequences of these restrictive clauses, in a weaker position to do anything about them and less likely to push back. That disadvantage, however, could come back to haunt them years later when they decide to make a career move.

What’s the final verdict on noncompete clauses? One cardiology industry leader well versed in contract language summed it up: “It’s simply not possible to write a noncompete that’s good for all parties—physician, group practice and hospital. So, the goal should really be for everyone to hate it equally.”