Measures of subclinical atherosclerosis differ by sex in heavy smokers

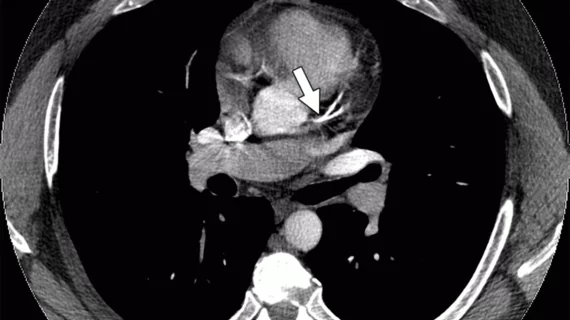

An analysis of more than 5,000 heavy smokers who underwent CT scans revealed that male smokers experienced a greater burden of coronary artery calcium (CAC) while women tended to have higher volumes of thoracic aorta calcium (TAC). Both measures were associated with increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, researchers reported in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

The case-control study featured 5,718 heavy smokers from the National Lung Screening Trial, all of whom had accumulated at least 30 pack-years and were between 55 and 75 years old at enrollment. It included every participant from the CT arm of the trial who died during the median 6.5 years of follow-up, along with about twice as many randomly chosen controls.

Interestingly, women had CAC burdens comparable to men 10 years younger. Eighty-one percent of men in the study had CAC detected upon CT compared to 60 percent of women. The median volume of CAC was 104 cubic millimeters in men and 12 mm3 in women.

TAC, on the other hand, was present in almost equal numbers of men (92 percent) and women (93 percent), with median volumes slightly higher in women (404 versus 388 mm3).

“CAC develops later in women, whereas TAC develops equally in both sexes,” lead author Nikolas Lessmann, MSc, with the Image Sciences Institute at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, and colleagues wrote. “CAC is strongly associated with coronary heart disease, whereas TAC is especially associated with extracardiac vascular mortality in either sex.”

Men in the study experienced about five more deaths per 1,000 person-years than women (13.3 versus 8.1) and also had significantly higher death rates for cardiovascular disease and coronary heart disease. However, extracardiac vascular causes of death—which encompassed CVD deaths not related to coronary heart disease—occurred at a similar clip between sexes.

Compared to participants with zero CAC at baseline, those with any CAC demonstrated more than double the rate of all-cause mortality and more than triple the rate of cardiovascular mortality. Individuals with CAC tended to be sicker overall, but the associations with mortality remained even after adjustment for traditional risk factors.

Lessmann et al. cautioned their results among smokers shouldn’t be extrapolated to the general population, where the prevalence and severity of CAC and TAC are likely to be lower. Also, the use of ungated CT scans may have overestimated the calcium burden in participants versus what may have been seen with gated scans.

Still, the authors said it was “remarkable” CAC was absent in 28 percent of their cohort considering participants were all 55 or older and had 30-plus pack-years of cigarette smoking history.

In a related editorial, Michael D. Miedema, MD, MPH, pointed out long-term smokers without any CAC still die at roughly twice the rate as nonsmokers without calcified atherosclerotic plaque. With this in mind, he said these individuals may be uniquely resistant to developing CAC but shouldn’t be presumed to be at low risk.

“In individuals with a significant smoking history undergoing CT screening for lung cancer, the presence and amount of CAC and TAC does carry prognostic value and should be discussed with patients to help reinforce the need for aggressive preventive measures, especially smoking cessation,” wrote Miedema, with the Minneapolis Heart Institute. “However, the absence of CAC and TAC in this population should not be used to provide false reassurance as being at lower risk does not necessarily mean low risk.”