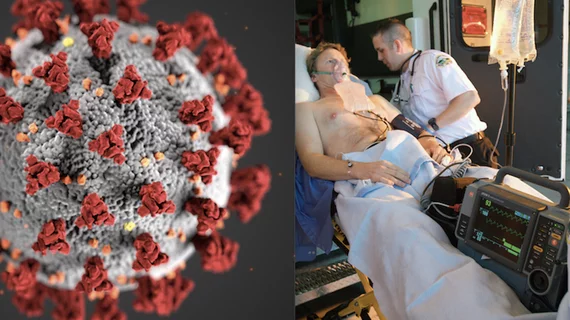

Hospitals still struggling to reach pre-COVID heart attack care thresholds due to pandemic disruption

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, obstacles like the need for COVID-19 screening, associated isolation procedures and terminal cleaning in the cardiac cath lab led to increased door-to-balloon (D2B) times. According to a new study, presented at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) Quality Summit 2023, many healthcare facilities are still recovering from the pandemic and facing new challenges, causing D2B times to continue to lag.

The standard of care has been for D2B times of 90-minutes or less to improved outcomes in patients with an ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Delays in restoring reperfusion are associated with higher rates of mortality and morbidity. Some delays may be unavoidable, including uncertainty about diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of other life-threatening conditions, delays around informed consent and long transport times due to geographic distance or weather.

But the lower D2B times later in the pandemic until today appear to be caused by several factors, including a shortage or nurses and clinical staff and loads of experienced staff familiar with STEMI protocols pre-pandemic. The standard practices of per-hospital notification and other standards were also impacted by disruptions during the pandemic and were not universally re-established after the COVID emergency ended.

In April 2022, Hackensack Meridian Ocean University Medical Center’s (OUMC) National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) CathPCI data for the first quarter revealed a climbing D2B time of 73 minutes, which was well below their goal of 60 minutes. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, OUMC had averaged around 60 minutes for approximately two years.

“Some of the new national standards created in response to the COVID-19 pandemic created obstacles to heart attack care by adding minutes to D2B time. Although the incidence of COVID myocarditis increased during the pandemic and led to false activations, the total number of STEMI activations actually decreased,” Sara Belajonas, MSN, MBA, CCRN, APN-C, chest pain coordinator at Ocean University Medical Center in Brick Township, New Jersey, and author of the study said in a statement from ACC. “I believe this created a scenario that our STEMI process was not utilized as often, therefore creating the need for re-education and the refocusing on the importance of time.”

Reasons for lower heart attack response times during and following the pandemic

According to the authors, heart attack hospitalizations decreased by 28% globally during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is suspected this is not due to a lower incidence of heart attack during this time, but because patients did not seek medical treatment. This emerged early on in the pandemic as a big problem, where patients did not want to seek help at a hospital because of the fear of contracting COVID as pandemic patients filled emergency departments.

“We can learn a lot from these trends to help prepare ourselves for the future. Community education is imperative,” Belajonas explained. “Utilizing past research and trends, we already know symptomatic patients are not getting the emergency care they need. All healthcare workers should do their part in educating the public on the importance of early heart attack care.”

During a review of the heart attack care processes, researchers examined the door-to-ECG (electrocardiogram), arrival to STEMI activation, arrival to case start and D2B. This review process determined that patients were spending too much time in the emergency room for an assortment of reasons that affected patient throughput and demonstrated the need for aggressive refocusing on time and process.

The Ocean University Medical Center study also found that not all STEMIs brought in by emergency medical services (EMS) advanced life support units were pre-activated. This is when EMS notifies in advance of arrival the cardiac cath lab at the hospital where the patient is being transported to. This can allow patients to bypass the typical protocol of going to the emergency department first and instead go directly to the cath lab and giving staff time to prepare to receive the patient. This can save critical minutes.

“I absolutely think other facilities face similar issues. One major issue arising from the COVID pandemic is national nursing and EMS shortages. These shortages hinder D2B and EMS to balloon times,” Belajonas said. “Many of these shortages unfortunately started during the COVID pandemic and have been linked to burnout. Simply, the demand for nurses and EMS workers outweighs what is available.”

According to the authors, the ongoing shortages of healthcare and EMS workers is concerning for future public health crises and STEMI care. Ongoing staff education will be key to ensuring stable processes and time management, as well as feedback and drills to identify gaps and opportunities. Research comparing pre- and post-COVID STEMI trends found a decrease in STEMI activation post-COVID, which was supported by OUMC’s own experience. There has also been an increase in STEMI over the last few months, according to Belajonas, who suspects we will see these trends repeat themselves as COVID numbers rise and fall.

How OUMC re-established its STEMI D2B time protocols

Some of the processes that were implemented at Ocean University Medical Center to reduce D2B times included:

• Re-education of the multidisciplinary team

• Involvement of additional staff to assist in the process

• Review of all STEMI cases with time interval drill down

• Re-education on ACC recommendation to pre-activate all field STEMIs regardless of transmitted ECG

• Re-education on STEMI prep

• Annual STEMI drills completed, including new heart and vascular to familiarize staff with cath lab 1 and 2

• Collaboration with EMS to drill down transport delays

At the end of 2022, OUMC's D2B time had been reduced from 73 minutes to 72 minutes. But with continued education and stressing a return to pre-pandemic STEMI protocols, in August 2023 they made their goal of 60 minutes.