Can FFR Safely Guide CABG?

Research supports the safe and effective use of fractional flow reserve (FFR) to guide PCI. Now some experts suggest FFR has a role in CABG because of its potential to spare patients a complicated surgery as well as cut costs.

FFR earned its place as the “gold standard” tool for assessing coronary artery stenosis and guiding PCI through the landmark FAME (Fractional Flow Reserve Versus Angiography in Multivessel Evaluation) studies. The FAME trial randomized more than 1,000 participants to undergo PCI guided by either angiography alone or by angiography and FFR (N Engl J Med 2009;360:213-224). The primary outcome—a combination of death, MI and the need for repeat revascularization—occurred less frequently in the FFR group and patients in the FFR group also had a decreased need for repeat revascularization.

The follow-up FAME II study showed that the need for urgent revascularizations in a population of patients with flow-limiting lesions (defined as FFR less than 0.8) was reduced by 86 percent for patients who underwent FFR-guided PCI compared with those treated with only medical therapy.

However, little is known about the impact of FFR on CABG, although some experts argue it could potentially prove its worth in patients undergoing treatment.

“Over the past several years, there’s been increasing recognition that most events in patients with coronary artery disease, at least in the short and intermediate term, meaning several years, are going to arise from lesions that produce ischemia,” says Gregg W. Stone, MD, professor of medicine at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City. “We can detect which patients have ischemia-producing or related lesions with fractional flow reserve in the cath lab.”

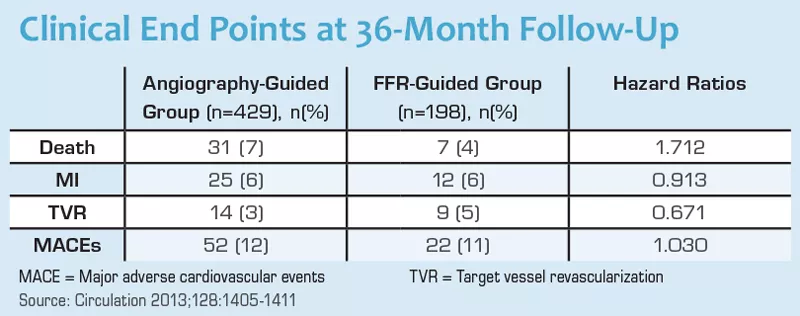

One study found better outcomes in patients who underwent FFR-guided CABG compared with angiography-guided CABG (Circulation 2013;128:1405-1411). A team of researchers from the Cardiovascular Center Aalst in Belgium evaluated outcomes from 627 consecutive patients who underwent CABG with at least one angiographically intermediate stenosis. CABG was guided solely by angiography in 429 patients and by FFR in 198. In the latter group, at least one intermediate stenosis was grafted with an FFR of 0.8 or less or deferred if FFR was more than 0.8.

Compared with the angiography-guided group, there were fewer single, two to three and four or more graft anastamoses in the FFR-guided group, (42, 217 and 170 vs. 39, 113 and 46), significantly less angina (31 percent vs. 47 percent) and fewer on-pump surgeries (49 percent vs. 69 percent). The groups were similar in terms of adverse cardiovascular events three years after the procedure.

From anatomy to physiology

There also has been a shift away from anatomic evaluation of vessels toward physiologic evaluation, suggesting that FFR may be useful, argues T. Bruce Ferguson, Jr., MD, of East Carolina Heart Institute in Greenville, N.C. FFR and other physiologic data combined with anatomic data predict which vessels need PCI. These same data may be of value in CABG as well.

“A lot of the imaging work we’ve done in the operating room at the time of surgery provides real-time physiologic data to support the idea that physiologic consequences of revascularization are really important in bypass surgery,” Ferguson says.

Two pivotal clinical trials comparing CABG and PCI found that bypass surgery offers a survival benefit over PCI in some patients. In SYNTAX (SYNergy Between PCI With TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery), PCI patients were more likely to experience the primary outcome (death from any cause, stroke, MI or repeat revascularization) compared with CABG patients (17.8 percent vs. 12.4 percent). In FREEDOM (Future Revascularization Evaluation in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: Optimal Management of Multivessel Disease), the primary outcome of a composite of death, nonfatal MI or nonfatal stroke occurred in 26.6 percent of the PCI group and 18.7 percent of the CABG group.

“It may very well be because it’s the physiologic consequence of revascularization that actually is the mechanism by which surgical patients have better survival and better freedom from myocardial infarction,” Ferguson explains.

FFR also may help determine the role that the physiology of the distal myocardium plays in assessing graft patency. If an area of the myocardium had enough blood flow and didn’t need to be grafted, then that could help explain why graft attrition occurs.

Although he believes his colleagues need to rethink the traditional anatomic strategy for revascularization, he stresses that there is still not enough evidence to firmly support the use of FFR-guided CABG.

Fewer surgeries, lower costs?

FFR-guided CABG may offer other advantages as well. Research has found an FFR of less than 0.8 to predict ischemia-producing coronary stenoses with more than 90 percent accuracy (Circulation 2013;128:1393-1395). By identifying lesions that are ischemia-producing with FFR, surgeons may only have to graft those vessels and not others, even if they look stenotic with some degree of atherosclerosis, Stone explains. Therefore, the procedures would be shorter with fewer complications, there may be a shorter stay in the coronary care unit, less bleeding and grafts could be preserved for later use if necessary.

FFR-guided CABG also may offer cost savings by reducing the number of surgeries performed after FFR analysis. “Over the long haul, PCI and CABG cost about the same,” says Peter K. Smith, MD, of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C. At first, he explains, PCI is less expensive, but over time, revascularizations, repeat interventions and a lack of durability add to the cost.

Stone adds that FFR involves giving adenosine and using a guide catheter and FFR wire as well as other equipment. There are also the costs of additional time in the cath lab and rare complications from adenosine or the wire. “Those costs would be recaptured by less bleeding, fewer reoperations and a shorter coronary care unit stay, but that all remains to be shown,” he says.

Paucity of evidence

In addition to sparse data in support of FFR-guided CABG, Smith argues that patients with three-vessel disease and diabetes could lose the mortality benefit that CABG offers. Although angiography would classify them as having three-vessel disease, FFR measurements may indicate less than three-vessel disease, meaning they would not receive intervention on all vessels.

“FFR will find some of these patients have significantly less functional disease than anticipated and now may be better off with PCI or medical treatment,” Stone adds.

Smith also cautions that the consequences from graft or stent failure are unclear. So far, evidence may suggest that stent failure is worse than graft failure. On the other hand, an unnecessary stent could bring many harms and no benefits, but whether the similar harms would befall someone with an unnecessary bypass graft is uncertain.

The true potential FFR-guided CABG remains a question that only may be answered by additional prospective studies.