Black, rural and low-income PAD patients are less likely to receive high-quality care

Black, rural and low-income patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) are less likely than white or higher-income urban patients to see a primary care provider or vascular specialist and undergo lower extremity revascularization to prevent extremity amputations. This is according to a new study in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, which found persistent disparities in outcomes for patients with PAD and its more severe form of chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) in the United States.[1]

“Every patient that has an amputation for CLTI represents a failure to deliver quality care aimed at amputation prevention. This includes revascularization, which has a clear benefit in preventing major lower extremity amputation," explained study co-author Alexander Fanaroff, MD, an interventional cardiologist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine, in a statement sent to Cardiovascular Business. "It’s easy to find and point out procedures that shouldn’t have been done, but it’s harder to find and point out procedures that should have been done but weren’t. This research is a start in that direction. This research should be a call to health systems, policymakers and other stakeholders to make it easier for patients—especially the most vulnerable patients—to access PAD-specific care.”

The study looked at patients ages 66-86 with fee-for-service Medicare who underwent major lower extremity amputation for CLTI from July 2010 to December 2019. The researchers looked at the proportion of patients who received vascular care in the 12 months before amputation by race (Black vs. white), location and socioeconomic status (SES) and other factors.

Among the 73,237 patients who underwent major lower extremity amputation, 55.1% had an outpatient vascular subspecialist visit, 82.1% had lower extremity arterial testing and 38.7% underwent lower extremity revascularization in the year before amputation. Black patients were less likely to have an outpatient vascular specialist visit or revascularization than white patients. Compared with patients without low SES or residing in urban areas, patients with low SES or residing in rural areas were less likely to have an outpatient vascular specialist visit, lower extremity arterial testing or revascularization.

Patients with low SES were substantially less likely than patients without low SES to have both vascular surgeon (31.9% vs. 38.3%) and cardiologist (26.7% vs. 40.1%) visits in the year before amputation.

Median times from lower extremity arterial testing and CLTI diagnosis to amputation were shorter for Black patients, those living in rural areas and those with low SES. This indicates that they are seeing doctors too late with very advanced disease when options are limited for limb salvage and undergo amputation without an attempt at revascularization. The authors of this study said these amputations were all potentially preventable if there were better design of care systems of CLTI care, and disparities in pre-amputation vascular care were addressed.

While the majority of amputations were attributed to rural patients who may not have easy access to care, overall, 44.1% patients who underwent amputation lived in metropolitan areas with more than 1 million residents. All patients living in these large urban area ZIP codes had access to care, but did not receive it. The study found 92.4% of hospital admissions were to centers that performed lower extremity revascularization procedures.

The key takeaway from the study was that Black race, rural residence and low SES are associated with failure to receive subspecialty CLTI care before amputation. To reduce disparities in amputation, the researchers said multi-level interventions to facilitate equitable CLTI care are needed.

Rising PAD prevalence and the need for community outreach

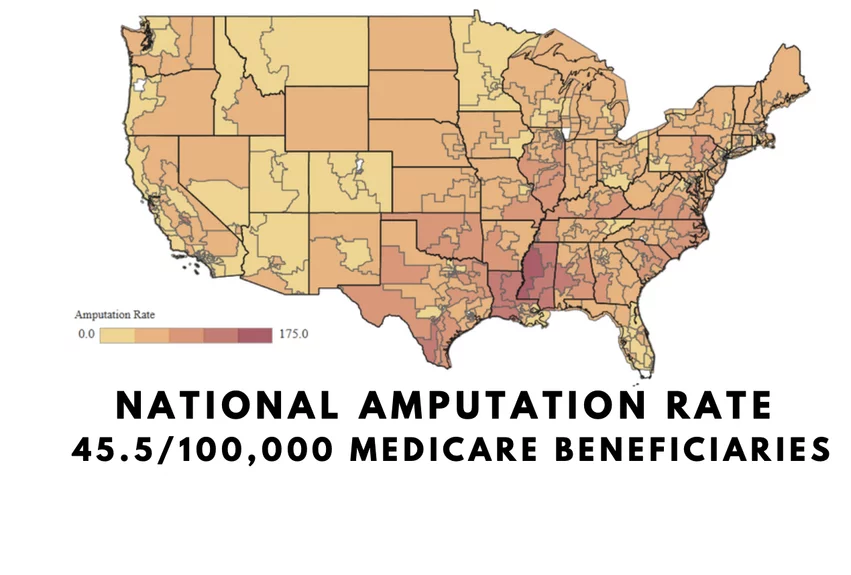

The authors point out that vascular disease affects 10-20% of older adults worldwide. In the United States, there are rising concerns about the widening health disparities in amputation rates with Black, Hispanic, Native American and low-income rural patients. The trend with Black and Hispanic patients is seen not only in rural regions, but also in low-income minority urban areas across the country, where ZIP code and neighborhood are major factors in predicting the level of care and amputation rates.(2)

The authors said this study concentrated on Black patients because they were easier to identify in Medicare data. They said Medicare’s enrollment race and ethnicity data are less accurate for beneficiaries identified as American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian/Pacific Islander, or Hispanic than for Black and white patients. Patients with low SES were defined as those with dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid, a strong marker of poverty and a proxy for social risk, they said.

There is growing recognition of these disparities and the need to diagnose PAD patients much earlier, when It is easier to treat them and prevent amputations. This past year a large patient and referring physician education outreach campaign was started by a coalition of physician medical societies. The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), Association of Black Cardiologists (ABC), Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), and the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS), formed the PAD Pulse Alliance and the Get a Pulse on PAD outreach campaign.