Cardiologist moves to Mississippi to fight back against PAD and limit amputations

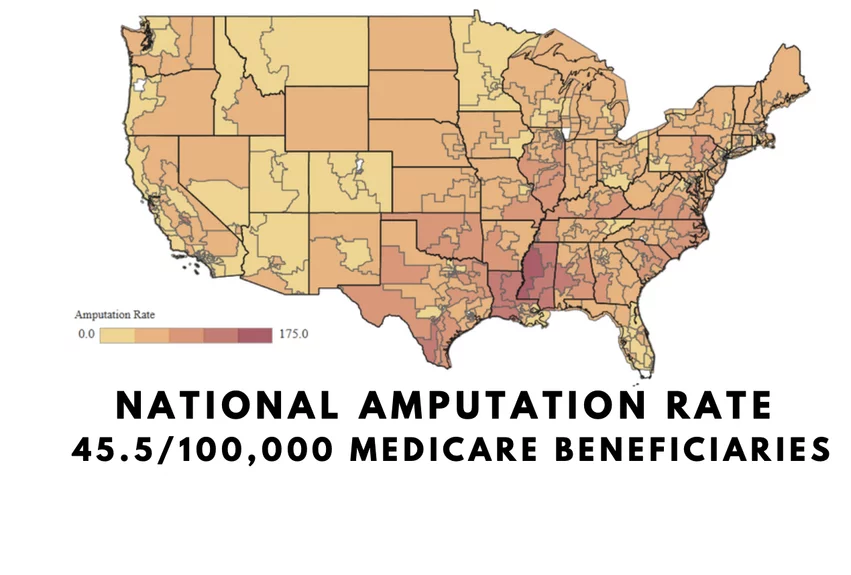

In the heart of the Mississippi Delta lies a silent epidemic that has long plagued the community. It has the highest incidence rates in the country for peripheral artery disease (PAD) and critical limb ischemia (CLI), and these conditions have resulted in a staggering number of leg amputations. Each day nationally, about 400 CLI amputations procedures are performed, and a disproportionate number of these take place in Mississippi. But amid the shadows of despair, one man has stepped forward to confront this crisis head-on.

Foluso Fakorede, MD, is no stranger to adversity. Trained as an interventional cardiologist, he witnessed firsthand the toll of PAD and CLI. He saw how the disease disproportionately impacts low-income areas, especially Black communities. He said he wanted to do something that would make a difference and this call of duty led him to the Deep South Mississippi Delta in 2015. Establishing his practice in Cleveland, Mississippi, Fakorede embarked on a mission to transform the landscape of cardiovascular care, which went beyond normal care in include education and community engagement.

"The region where I serve has the highest amputation rate in the country with the lowest number of not only physicians per capita, but it's a vascular desert where there are not a lot of vascular surgeons, interventional cardiologists or interventional radiologists. So I felt the need to bring my skillset down here," Fakorede explained.

He said personal engagement in this rural Black community was key for him to get health messaging out to where patients and their facilities could hear it. Although he is Black, he was raised and trained in the north, so he was initially met with skepticism about why he wanted to set up shop in their community. However, he changed people's minds when he offered a chance to preserve limbs and not just offer amputation as old gold standard of care in the region.

One of the biggest obstacles he encountered was that the vast majority of patients and their families had never heard of PAD or CLI before, and often their health literacy was poor.

"We talk about strokes, we talk about heart attacks, we talk about heart failure and arrhythmias, and a lot of our patients actually are aware these things, but less than 20% of people have heard of the term 'peripheral artery disease,'" he explained.

Fakorede said he opened his practice in a rural area where patients often drive long distances just to receive basic cardiac care.

"A lot of them drive about 45 minutes to an hour to come and see a provider for just a heart checkup, a stress test, let alone if they have a history of diabetes. When they had poor circulation historically before I got here, amputation was the strategy that was offered, and that was kind of the generational norm," Fakorede explained.

Many portions of the delta are also a food desert and poor diet adds to the cycle of disease. He said patients often explain that one or both of their parents have already had an amputation due to diabetes. But Fakorede is trying to break the cycle by telling patients that there are upstream strategies they can use, including not only lifestyle and dietary modification, but medication therapies that combat their risk factors. He said education also concentrates on linking diabetes to the progression of plaque buildup and the progression of the disease.

"Eight in 10 people here have never heard the term or have not linked PAD to an amputation. But if you walk through a Walmart or a grocery store here, you'll see a patient, an amputee with a walker and the tennis balls at the bottom, and some of 'em with dialysis catheters, and see there is an epidemic going on. It's just people are not linking their poor social determinants to it. "

Fakorede's efforts have helped reduce amputation rates by more than 80%

Fakorede said he picked the delta region to because he felt he could make a sizable impact their on public health. And true to his word, within just a couple years of practice and education efforts, he was able to make a sizable dent in the area's statistics.

"We led an 87.5% decrease in amputation rates over a four and a half year period. But I think a lot of the work has been seeking out partnerships with community and societal partnerships to see how we can best address this in other communities that look like ours. It's not just the Black community, it is the Hispanic community and the Native American communities that actually have higher disproportional rates of peripheral disease," Fakorede explained.

These efforts led to awards from national medical organizations and praise from his peers. The American Heart Association, for example, gave him a Louis B. Russell Award, which is a community engagement award for seeking out his community and addressing the disparity in treatments and outcomes

"I tell people the key to community engagement and success is the ability to stay put and to stay the course and let them see you and see your growth and see that you are committed to them. Because it's not just having something nice written on a piece of paper saying we engaged the community. No, it is about whether you can sustain that relationship and that engagement for two years, for four years, for six years, for eight years, and are you giving back in different forms to the community. The point is to believe that when your purpose is just and your mission is true, there are going to be obstacles, but they shouldn't come in your way. And you should find partnerships as I've done to help you achieve that goal," Fakorede explained

Examples two of Dr. Fakorede's patients who presented with unhealing wounds on toes and feet due to advanced critical limb ischemia (CLI). Prior to him establishing an interventional practice in the area, most of these patients underwent major amputations of the feet or the leg below the knee. He said patient education is also crucial to prevent their condition from getting this bad to start with.

Building trust in the rural Black south

Central to Fakorede's approach was the cultivation of trust and understanding. As a Black physician serving a predominantly Black community, he recognized the importance of cultural concordance and linguistic sensitivity in fostering meaningful connections with his patients.

"I did not grow up in the south, so some of the terminology I used was not concordant with theirs. For instance, people will say, 'I've had the sugar for a long time.' Well, the 'sugar' is diabetes. They will say 'I've had pressure for a long time.' Well, that's high blood pressure," he explained.

Tobacco use is a major risk, but asking if a patient smokes is not helpful in the Delta because most will say no. Fakorede said most people there actually dip and chew tobacco since they were children, so the risk is the same, but from a different vector.

Then there are different social structures in the delta region, where children are often the care takes of their parents or family members in ill health.

"So the correlation needs to be in terms of meeting them at not only on their literacy level, but speaking their language, and then going to their civic organizations, their churches, and going to their schools, because kids are taking care of adults these days in the community at home. They're the guardians, they're the caretakers. So it's important for us to kind of meet them at different levels and educate them as to what cardiovascular disease is," Fakorede said.

Read related interviews with Fakorede here:

Cardiologist details the many health disparities he encounters in rural Mississippi

Health disparities are causing serious harm, leading to 400 amputations per day