Mitral Mysteries: Imagers Explore a New Frontier in Transcatheter Valve Replacement

The continuing success of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has inspired the cardiology community and device makers to venture into a new frontier: transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR). TAVR offers valuable lessons that can be applied to TMVR, according to imagers on the frontlines for both techniques. But be prepared to face more challenging terrain and to blaze new trails to achieve equally good outcomes.

It is nearly 15 years since Alain G. Cribier, MD, and his team performed the first percutaneous implantation of a bioprosthetic aortic valve in a critically ill patient with aortic stenosis. Now the procedure is approved in the United States for patients with severe aortic stenosis who are inoperable, high risk and, as of mid-August, at intermediate risk. But the journey from the first-in-humans case study to a growing body of evidence showing favorable outcomes, fewer complications and an increasingly streamlined procedure wasn’t always smooth.

“In truth, people sometimes forget the difficulties at the beginning of the TAVR program,” says Rebecca T. Hahn, MD, director of interventional echocardiography at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City and a member of Columbia’s pioneering TAVR heart team. “It seems so easy now when you look back, but it has [taken] 10 to 11 years since the initial clinical trials for us to get to this point.”

TMVR is likely to benefit from the knowledge gained with TAVR. For instance, TAVR clinical trials initially called for echo for preprocedural planning but protocols now favor CT after physicians at St. Paul Hospital in Vancouver and other research groups showed CT was better for assessing the annulus. That led to more accurate valve sizing and reduced the risk of paravalvular regurgitation and its associated poor outcomes. Echo remains the preferred intraprocedural modality. “What we learned from TAVR is that it is all about multimodality imaging and using all your tools,” Hahn says. “Certainly we are so much further ahead on the mitral valve because of that experience.”

Philipp Blanke, MD, co-director of the core lab at St. Paul Hospital, adds that radiologists learned not only how to use CT for sizing but they also refined CT-based techniques for screening patients, assessing anatomical risk, access planning and C-arm angulation in the cath lab—knowledge that can be transitioned to TMVR. “We didn’t have to wait six years to find out if we can use CT to identify the C-arm angulation in the mitral valve because it has been described for the aortic,” he says. “We just have to apply that knowledge and that thought process to the mitral space.”

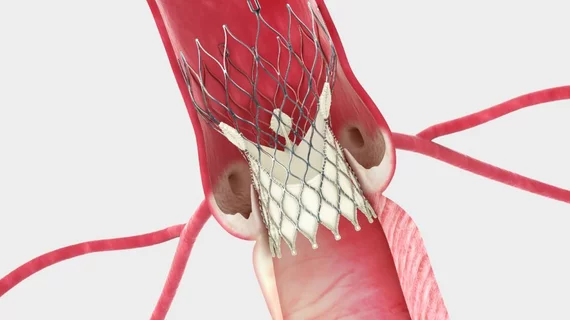

Hahn, Blanke and others who study structural heart therapies collaborated on a state-of-the-art paper that advocated multimodality imaging for TMVR (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8[10]:1191-208). They cautioned that compared with the aortic valve, the mitral valve is anatomically and functionally more complex and dynamic, and that mitral regurgitation is a different disease from aortic stenosis. Mitral regurgitation can be either primary/degenerative disease or secondary/functional disease. But as with TAVR, TMVR will require accurate assessments of the annular and landing zone geometry to select appropriate patients and to optimally size devices in order to avoid complications such as paravalvular leak and unintended obstruction of nearby anatomy.

Landing zone issues with transcatheter mitral valve deployment

The mitral valve’s annulus is not elliptical but rather a nonplanar, saddle-shaped configuration. That traditional definition may not suffice for sizing and implanting TMVR devices, though, Blanke’s research team contends. They have proposed using an imaging method for sizing based on a D-shaped annulus (akin to a saddle with a truncated horn) that corresponds with the planar landing zone of some TMVR devices under investigation.

In one study, they analyzed electrocardiogram-gated CT scans from 28 patients with severe functional mitral regurgitation and hypothetically

compared the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) after TMVR based on either D-shaped or traditional saddle-shaped annular assessments (J Cardiovasc Compute Tomogr 2014;8[6]:459-67). They concluded that all of the patients with implantation based on saddle-shaped annular assessments likely would have experienced severe LVOT obstruction while sizing based on the more planar D-shaped assessment offered significantly more LVOT clearance. They added that although their analysis relied on CT, 3D echocardiography likely would provide similar measurements.

More recently, they retrospectively assessed CT datasets from 88 patients with no significant cardiac disease and 59 patients with moderate to severe mitral regurgitation who were being considered for TMVR. They used the D-shaped method to compare mitral annular dimensions (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9[3]:269-80). They found that annular dimensions were larger in patients with mitral regurgitation and the mean mitral annulus area was 18 percent larger in patients with mitral valve prolapse compared with patients with functional mitral regurgitation. This information may help inform sizing and the assessment of anatomical risk; it also suggests that the marketplace may require multiple devices to meet patients’ needs.

“Sizing is even more important for the mitral space because the anatomy is much more complex. But it is not only sizing; it is also the characterization of the landing zone,” Blanke says, noting the differences in anatomy between functional and degenerative mitral regurgitation. “The vast heterogeneity among all these pathologies and patients makes it very complex and very challenging for industry.”

Looking for imaging anatomical landmarks to guide TAVR and TMVR valves

Besides its more complex anatomy, a diseased mitral valve lacks the calcifications that serve as fluoroscopic landmarks during TAVR. With TAVR, preprocedural multidetector CT imaging determines the aortic annular plane, which is then confirmed periprocedurally on angiography for accurate valve deployment. Many TMVR trials call for transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) guidance in combination with fluoroscopy, but the lack of landmarks makes positioning a challenge, says Paul Schoenhagen, MD, a diagnostic radiologist at the Cleveland Clinic and co-author of a review on periprocedural imaging for TMVR.

The reviewers noted that echocardiography remains the standard for diagnosing mitral valve disease, measuring the annulus size and assessing severity preoperatively. Intraoperatively it is the primary modality along with angiography, with fluoroscopy assisting with guiding catheters and TEE with device deployment (Cardiovas Diagn Ther 2016;6[2]:144-59).

CT and magnetic resonance imaging are complementary modalities that might provide additional information, they wrote. The lack of a landing zone may present one of those opportunities.

Schoenhagen and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic have developed a surrogate landmark using the coronary arteries, which can be detected fluoroscopically. In a retrospective study of 25 patients with gated cardiac CTs, they constructed a plane defined by the left circumflex-right coronary arteries and showed that it appeared to correlate reliably with the mitral annular plane (Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2016 Apr; 6(2): 144–159. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2016.02.04). Similar to TAVR, they proposed, preprocedural CT could determine the relationship between these two planes, and fluoroscopy as a complement to TEE could help with positioning and deployment.

“To some extent, you know the relationship between the coronary plane and the annular plane,” Schoenhagen says. “In that way, you would create a landmark that you would not have otherwise.”

3D visualization is needed to navigate transcatheter devices in complex mitral anatomy

No matter which modality is used, it should allow for 3D reconstructions to visualize the anatomy and help the heart team navigate this complex mitral terrain, says Schoenhagen, who also supports the use of multimodality imaging. “The acquisition of the three-dimensional dataset is something that comes naturally for CT because that is how CT is acquired. For the other modalities, for 3D echo, certain 3D sequences with [MRI], that is also possible and increasingly possible.”

Hahn, who co-chaired TEE guidelines for the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2013;26[9]:921-64), says that with TAVR, improvements in imaging technologies occurred in parallel with improvements in TAVR techniques. She expects the same to occur with TMVR.

She points to the commercial availability of real-time 3D TEE in 2007, which improved visualization of the valve anatomy and put the imager and interventionalist more in sync. “Even though we are not seeing the same plane as they are seeing, they are able to translate pretty easily our anatomy to what their catheters are doing,” she says.

Imaging technologies in development that fuse 2D or 3D echocardiographic imaging onto a fluoroscopic screen “will make communication even easier and the interventionalist will no longer have to do that mental reconstruction,” she says. “It is all coming together. The technology for these new transcatheter valves as well as the technology for imaging is being developed simultaneously for advancing the structural field.”

Find more structural heart news and video

VIDEO: How to build a structural heart program — Interview with Charles Davidson, MD