New patient-specific heart models could change how cardiologists make treatment decisions

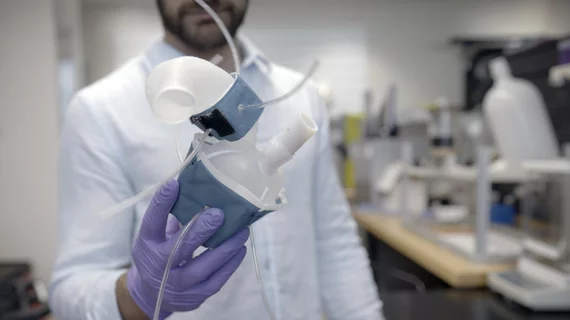

Engineers and cardiologists have developed a new way of converting cardiac imaging results into soft, flexible models of a patient’s heart, sharing their work in Science Robotics.[1]

The team’s 3D-printed models are functional in ways that could potentially make a significant impact on patient care. They can duplicate the way the heart pumps blood, for instance, and even mimic aortic stenosis (AS).

“All hearts are different,” first author Luca Rosalia, a graduate student with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), said in a prepared statement. “There are massive variations, especially when patients are sick. The advantage of our system is that we can recreate not just the form of a patient’s heart, but also its function in both physiology and disease.”

This research represents a collaboration between MIT, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard University and Cleveland Clinic. The group printed its new-look heart models using a polymer-based ink that can be squeezed and stretched, using cardiac CT images from 15 patients who had been diagnosed with AS. Sleeves were also developed that could be wrapped around the heart models to mimic what happens when the heart pumps.

“Being able to match the patients’ flows and pressures was very encouraging,” co-author Ellen Roche, PhD, with the MIT School of Engineering, said in the same statement. “We’re not only printing the heart’s anatomy, but also replicating its mechanics and physiology. That’s the part that we get excited about.”

The researchers also found that performing interventions on the heart models led to the same improvements one would hope to see if performing the intervention on a patient. Implanting heart valves, for example, helped the blood pump through a 3D-printed heart like it would an actual heart.

The group hopes their findings can lead to key improvements for heart patients. Cardiologists could potentially use a 3D-printed heart model to see which size of a device will be the best fit for a specific patient—or which intervention may lead to the best patient outcome.

The full study is available here.