Searching for New Business: Hospitals Test the Waters of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

With its potential to tap into a myriad of hospital services and departments, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is drawing interest from medical centers committed to improving the lives of their patients and bolstering the bottom line.

Most cardiologists see only a case or two of HCM per year, and just a handful of hospitals nationwide have the expertise or experience to systematically treat the often genetically linked condition. But that backwater status hasn’t kept HCM from capturing headlines and shocking the public whenever seemingly healthy young athletes collapse suddenly on football fields, basketball courts or ice hockey rinks and succumb to sudden cardiac death. HCM is believed to affect one in every 500 individuals across all age groups, with some experts claiming its incidence could be twice that based on genetics and the fact that many cases are asymptomatic and go undetected until an electrocardiogram or echocardiogram is performed. HCM is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in individuals under 30.

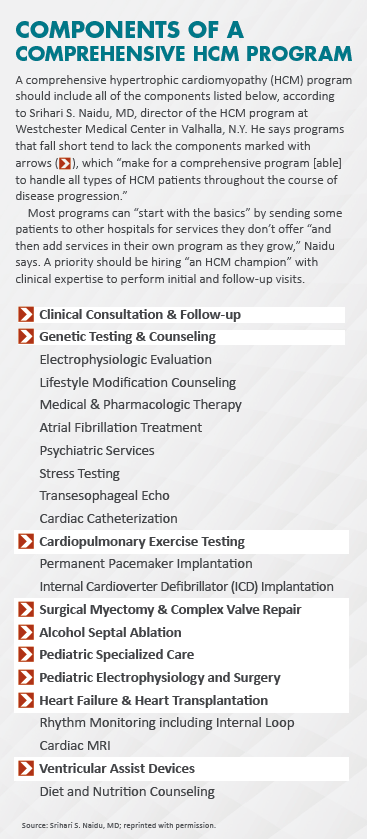

Hospitals are taking a long, hard look at the serious, multifaceted disease that can be effectively controlled by exposing patients to a vast array of medical resources, from surgery, interventional cardiology and pediatrics to genetic testing, psychiatric services and dietary counseling.

“These are heavy utilization patients who have been tremendously underserved in terms of improving the quality and longevity of their lives,” says Srihari S. Naidu, MD, director of the HCM program at Westchester Medical Center in Valhalla, N.Y., one of the largest programs of its type in the country. “Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is an area where hospitals can get a foothold and legitimately build important bridges with all sorts of hospital services.”

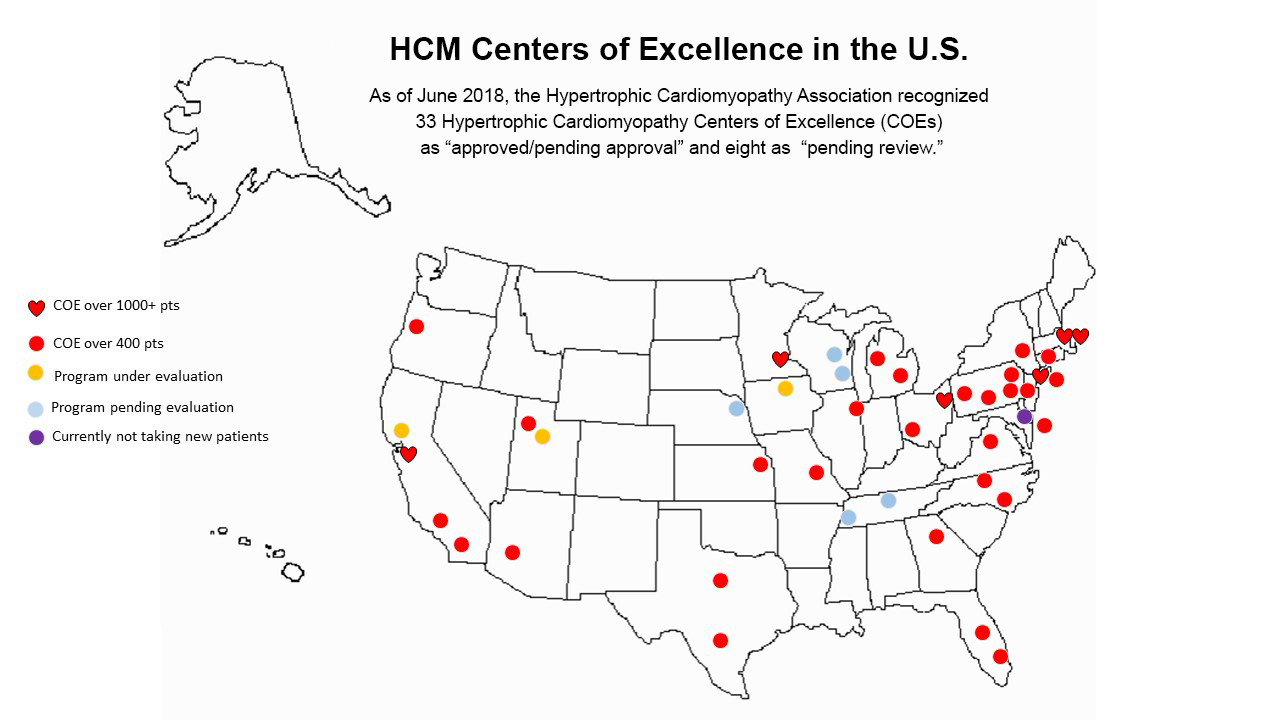

That the American Heart Association (AHA) has recommended all HCM patients be seen for advanced treatment at a dedicated center underscores both the challenges and the opportunities in this evolving area. While there are an estimated 30 U.S. medical centers that have achieved advanced certification for their HCM treatment program, fewer than 10 are believed to have a full complement of services, including surgical myectomy and alcohol septal ablation, the two most advanced forms of treatment.

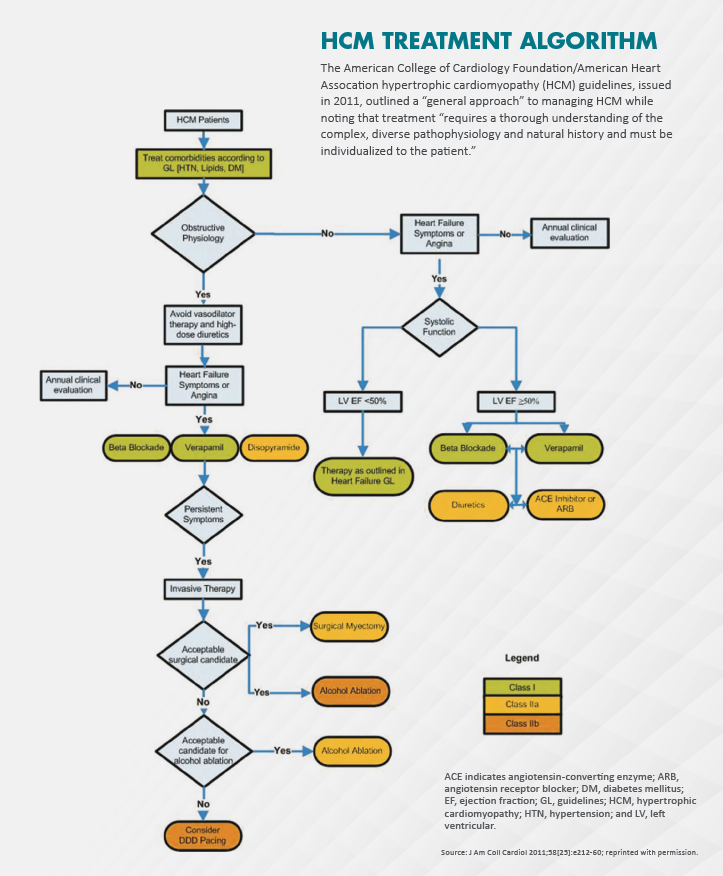

“This is not a disease you want to treat if you only see one patient a year,” says Bernard Gersh, MB, ChB, DPhil, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, and lead author of the first guidelines for diagnosing and treating HCM (J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58[25]:e212-60). “The one thing we heavily stressed in the guidelines is that all of these procedures need to be done in centers of excellence that are able to offer medical therapy, defibrillator, surgical myectomy, alcohol septal ablations and genetic counseling.”

An eight-year study of national hospital discharge records for patients undergoing advanced HCM procedures confirms that point. The researchers found that most medical centers offering surgical myectomy and alcohol septal ablation—procedures designed to reduce the thickening of the interventricular septum and enlarge the ventricular outflow tract—perform “few” such cases annually (JAMA Cardiol 2016;1[3]:324-32). According to the guidelines, individual surgeons, interventional cardiologists and treatment centers should have a cumulative caseload of at least 20 procedures and continue to perform eight to 10 successful procedures a year with acceptably low complication rates to ensure a prudent and appropriate level of experience.

The study also found that low-volume surgical myectomy centers experienced markedly worse outcomes than high-volume centers, including significantly higher mortality, longer lengths of hospital stay and higher costs. (Alcohol septal ablation in low-volume institutions, however, was not associated with worse post-procedural outcomes.) “More efforts are needed to encourage referral of patients to centers of excellence for septal reduction therapy,” the authors wrote.

OPTIMAL PATIENT VOLUME

Setting up and running a successful HCM program is anything but a slam-dunk. For one thing, not every hospital is cut out to be a center of excellence, nor is their catchment area sufficient to support an all-inclusive HCM program. Planners must carefully weigh the number of clinical and surgical patients a program is likely to draw, with large medical centers serving densely populated areas clearly enjoying a strategic advantage.

What is the optimal patient volume to support a program? Sherif Nagueh, MD, medical director of the echocardiography laboratory at Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Center in Texas, one of the highest-volume HCM centers in the country, believes the number is around 500. He points out, however, that the vast majority will be patients who are seen in clinics and doctors’ offices for ongoing management of symptoms that can be handled through medications or patients without symptoms who require regular monitoring. The smaller but in some ways more significant segment consists of individuals who require invasive, hospital-based therapy, particularly surgical myectomy or alcohol septal ablation.

“It’s not necessarily a smart move for a small hospital to undertake an HCM program because you need a large [patient] volume and satisfactory number of procedures to achieve good outcomes,” Nagueh affirms.

Westchester Medical Center’s HCM program, which formally launched in late 2016, currently numbers between 800 and 1,000 patients, and is growing at the rate of about 200 new patients a year. When he became active in the field some 15 years ago, Naidu says, there was a widespread belief that HCM patients were extremely rare and that a hospital could never build a viable business around this patient community.

“We now know there are many, many patients with this disease, and I estimate only 10 percent of them have actually been diagnosed,” he contends. “So there’s a huge opportunity here which hospitals are just starting to see, although it’s important they venture into this field with the right intentions and realistic goals.”

Magnifying that opportunity is the fact that HCM is a complex, potentially life-threatening disease—the most common inherited heart defect—that may require advanced imaging and genetic testing of entire families from an early age on.

NEED FOR A CHAMPION

Any hospital with designs on a full-blown HCM program would be well advised to jump-start it by hiring a recognized leader in the field, rather than attempting to gradually grow such an effort. When Westchester Medical Center hired Naidu with the explicit goal of creating a nationally recognized center of excellence, the institution leveraged his background performing alcohol septal ablations, experience building an HCM program from scratch at Winthrop-University Hospital in Mineola, N.Y., and his base of loyal patients.

“When we recruited Dr. Naidu it was relatively easy to put together a program around him with the components we already had in place, including imaging, pediatric cardiology, heart transplantation, cardiac pathology and genetic counseling,” explains Julio A. Panza, MD, chief of cardiology at Westchester Medical Center, who was among the first physicians in the U.S. to perform surgical myectomy in the mid-1980s while at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md. “And once we started building our program, patients started coming at a much greater rate than before.”

As experts in the field point out, the cost of undertaking a clinical program may be well within a hospital’s financial means if the building blocks for diagnosing and treating HCM are in place. “The investment required is mostly for physicians who will be dedicated to this program, and the staff that will be in charge of caring for patients and maintaining the database,” says Nagueh, whose HCM program at Houston Methodist DeBakey dates back to the late-1990s, when it became the first site in the U.S. to perform alcohol septal ablation.

After Naidu was hired to run Westchester Medical Center’s HCM effort and perform septal ablations, two surgeons already on staff underwent training at Mayo Clinic to master surgical myectomy, long considered the gold standard for septal reduction. In addition, a dedicated coordinator was brought on board to ensure that patients, particularly those requiring invasive therapy, moved smoothly through the system. The medical center also opened a satellite office in nearby Long Island to accommodate Naidu’s existing patient base and staffed it with an additional experienced coordinator. Within the first year, a nurse practitioner was also stationed at both offices.

It wasn’t long before HCM’s halo effect was visible across Westchester Medical Center. Because ongoing tests are necessary for physicians to characterize the phenotype of the disease—which often results in growing cardiac dysfunction and heart failure due to a thickened heart muscle—and determine the risks and need for certain interventions, multimodality imaging proved to be the greatest HCM revenue producer. According to Panza, in the program’s first year of operation, it spurred growth of approximately 15 percent in echocardiograms, 25 to 40 percent in cardiac MRIs and 20 percent in electrophysiology (mostly for the temporary pacemakers required for alcohol septal ablation but also for implantable devices and select arrhythmia ablations).

Though Westchester’s caseload includes a heavy volume of alcohol septal ablations (roughly three a month) and one to two surgical myectomies per month, the procedures amount to a tiny percentage of the hospital’s overall invasive activity. Still, they constitute the essential core of any HCM initiative and can have a spillover effect to other clinical departments. For example, a 90-year-old woman who was recently referred to Naidu with HCM and aortic stenosis may soon receive both a septal ablation and transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

ACTIVE REFERRAL SOURCE

Similarly, an in-place HCM program can be a boon for outside referrals, which benefit the hospital in many ways. “We get lots of referrals for many conditions, and not just from Texas but from as far away as South America and the Middle East,” says Nagueh. “And that helps us build our reputation because other hospitals know if they have an unusual case they can send it to us for expert care.”

But as Nagueh is quick to note, referrals must be earned, and that means ensuring strong and open communications between the HCM clinic and outside physicians to keep them fully apprised of the patient’s status and what steps need to be taken when they see that individual locally. As other HCM program developers point out, it makes eminent sense to court referring physicians at the outset of a program by holding introductory meetings (sweetened with CME credits) and preparing attractive brochures explaining the basics of HCM care that these doctors can leave in their offices for patients.

As part of its HCM operational model, Houston Methodist DeBakey also built a quality assurance platform. “Each center should apply quality assurance metrics, just like they do for percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass surgery,” says Nagueh. This program, he adds, should embrace quarterly or yearly clinical reviews of all invasive procedures to determine if surgical myectomy or alcohol septal ablation was the right decision, how the case was performed, what the outcome was and any complications.

Westchester Medical Center gave its HCM program operational ballast by hammering out protocols with all the relevant clinical departments to ensure, as Naidu puts it, “there is consistency and everyone is speaking the same language.” Thus, a new HCM patient doesn’t just get an echocardiogram. He or she gets an echo that adheres to well-defined HCM protocols. This mandate results in physicians knowing how high the obstruction gradients are, the septal thickness, its precise location and any potential mitral valve problem. These factors are important to determining not only if any interval change in anatomy has occurred but also whether a patient should get alcohol septal ablation or surgical myectomy.

HOW MANY CENTERS DO WE NEED?

Newer and safer approaches to treating HCM, such as echo-guided alcohol septal ablation with active-fixation temporary pacing, are helping to drive hospitals’ interest in HCM. But the comparatively small patient pool inevitably begs the question: How many HCM treatment centers does the country need? And where should they be located?

Experts in the field believe that a major metropolitan area should be able to support at least two centers offering a full range of services. These centers could even handle surgical or interventional referrals from smaller-scale HCM hospitals or clinics without the resources for advanced invasive therapy.

Some cities may already have a host of hospitals purporting to offer extensive HCM programs. A closer look, however, is likely to show many of them lacking the resources or volumes to substantiate that claim. To be sure, any hospital administrator considering a full-fledged program needs to determine if the geographic area is currently underserved by an HCM center of excellence and, if so, whether they have the clinical components in place to make a dedicated program financially worthwhile.

“Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy can be a wise move if done right,” Naidu says. “If not, a hospital can end up doing a serious disservice to their patients and their community.”