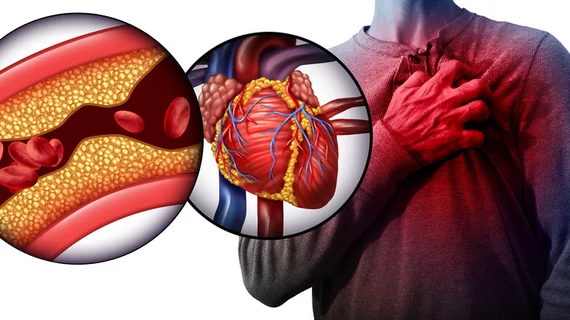

A fresh look at why high-fat diets can lead to atherosclerosis

Researchers in Japan are using mice models to gain a better understanding of why high-fat diets are associated with clogged arteries. The team shared its latest findings in JACC: Basic to Translational Science, noting that they hope it leads to improve treatment options in the years ahead.

Atherosclerosis, the authors explained, is an inflammatory disease sparked by the body’s response to what it views as an unwanted attack. White blood cells known as neutrophils are typically at the center of the body’s immune response—but things get harder to predict when the attack persists over time.

“We applied this theory to what happens in atherosclerosis—in this case, the persistent stimulus is dyslipidemia (unhealthy levels of fats and cholesterol in the blood),” lead author Mizuko Osaka, PhD, a specialist at Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU), said in a prepared statement. “So detailing the role of neutrophils in acute inflammation can help us understand how it becomes chronic inflammation.”

For their analysis, Osaka et al. examined how mice bred not to have LDL receptors (LDLR) on their cell membranes—making them more human-like—reacted to being fed a high-fat diet. The mice, it turns out, showed elevated levels of neutrophil adhesion to the walls of their blood vessels. They also developed high cholesterol and showed signs of inflammation.

“On the basis of certain biomarkers in the LDLR-null mice, we suspected that neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) could be involved in activating neutrophils,” senior author Masayuki Yoshida, PhD, another specialist from TMDU, explained in the same statement. “And indeed, we found enhanced citrullination of histone H3, a known marker of NETs, in these mice. Going further, we specifically identified plasma levels of CXCL1 (a peptide that acts to attract immune cells to the site of an injury or infection) to be significantly increased in the LDLR-null mice after seven days and 28 days of the high-fat diet.”

Blocking the citrullination process helped put an end to any neutrophil adhesion experienced by the mice, the team found—a sign that they may be on the right track to understanding why the human body reacts as it does to a high-fat diet.

The authors closed their analysis with a call for “clinical trials or global observations to monitor our findings,” hoping such work could lead to new tools and treatments in the fight against atherosclerosis.

Read the full study here.