Tackling the Rural Access Crisis: Cardiologists Will Need an Array of Tools to Meet Patients’ Needs

In an era of clinician shortages, those living in rural areas are at risk of not receiving needed care. Cardiologists are stepping up, but will it be enough?

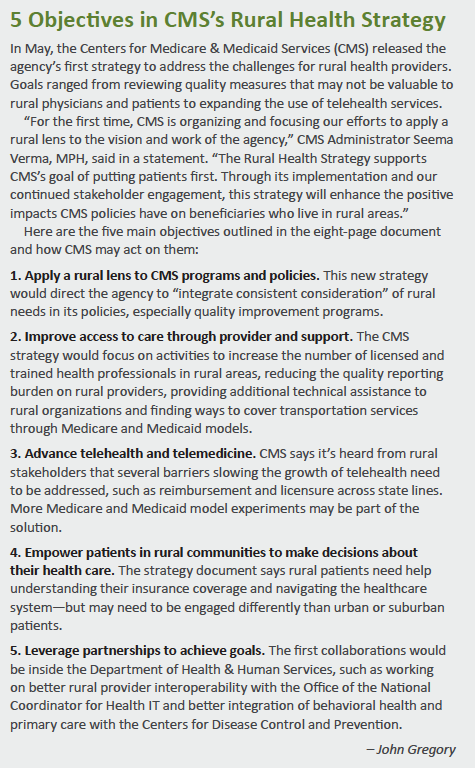

The demand for cardiologists is continuing to outpace supply. According to the Health Resources & Service Administration, rural America is home to more than half of the health professional shortage.

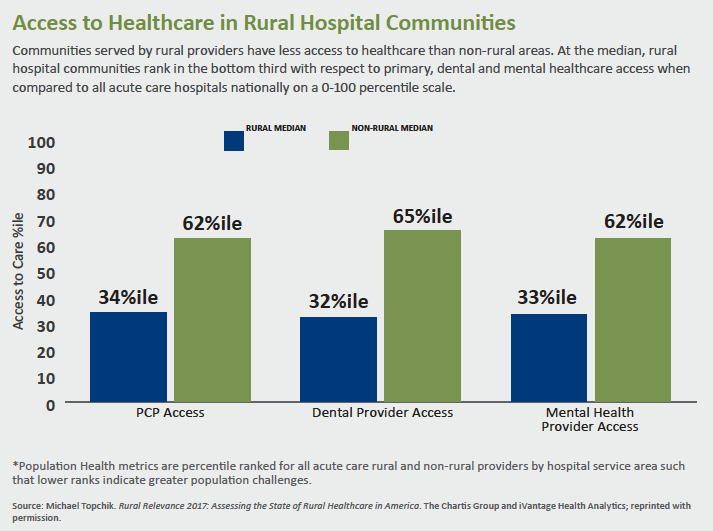

And it’s not just physicians: At least 83 rural hospitals have closed since 2010; another 600+ facilities are considered vulnerable. The Boston-based Chartis Group’s center for rural health says 41 percent of hospitals are operating at a negative margin even as the National Rural Health Association warns that nearly 12 million patients are at risk of losing direct access to care.

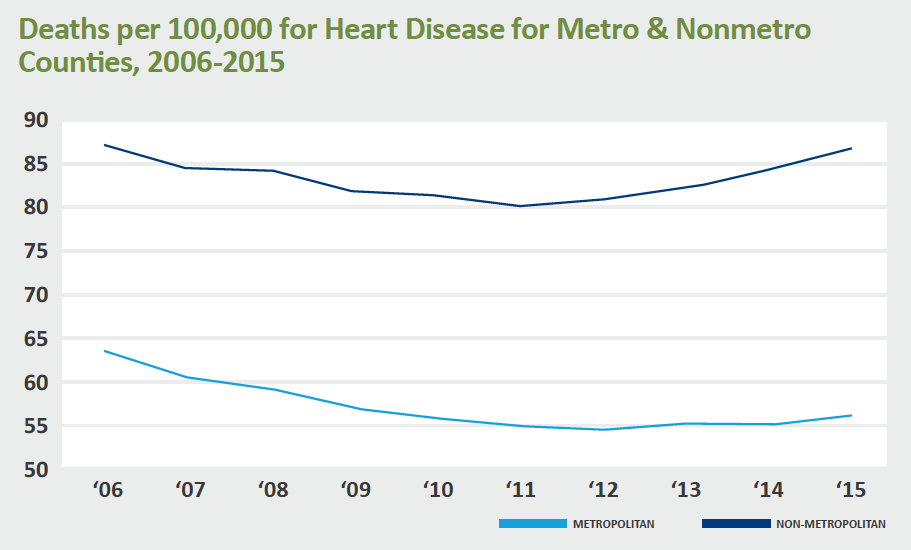

It’s little surprise then that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Americans living in rural areas are more likely to die from heart disease and stroke than their urban counterparts.

Cascade of factors

People in rural areas tend to be poorer, older and sicker than their urban counterparts. They also are more likely to smoke and be overweight or obese. They have higher rates of hypertension and opioid misuse, and lower rates of exercise and health coverage.

It’s a gloomy picture, one that can’t be blamed on geography alone. “These upstream factors are also contributing to the disparity in cardiovascular outcomes between rural and urban areas,” says Mark Holmes, PhD, director of the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

Moving downstream, access issues come into play. As Holmes points out, for example, rural populations are less likely to receive postacute care. Basic prevention is another issue—even for patients who have regular sources of care. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality, rural residents are less likely to get advice about smoking and exercise.

The effect is cumulative, Holmes says. “You have this long river where just a little more water is being poured into it, and by the end you have a deluge on the rural side and the much smaller stream on the urban side.”

Much more needs to be done than improving access to cardiovascular care. But it’s a good place to start.

Telehealth only part of the solution

Telehealth only part of the solution

Start talking about rural outreach and access, and telemedicine is often the first topic to come up. For good reason: A 2018 report from the Bipartisan Policy Center and the Center for Outcomes Research and Education found that telemedicine improves access by connecting rural patients with specialists and providing “much-needed peer support to rural health professionals who often work in professional isolation.”

One example of the latter is Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes), which trains rural primary care clinicians to provide specialty services. A team of providers—including specialty care and public health—holds weekly virtual sessions with community-based primary care clinicians. Although Project ECHO indicates it has not been an issue, participation does require broadband.

Perhaps it’s not an issue for ECHO participants, but for many communities, lack of broadband limits access to the full capabilities of telemedicine. According to the Federal Communications Commission’s 2016 Broadband Progress Report, 39 percent of rural Americans and 41 percent of Americans living on tribal lands lack access to broadband. Compare that to 4 percent of urban Americans.

Lack of broadband limits the opportunities for telemedicine, but it’s not an all-or-nothing proposition, Holmes says. Transmitting scans may not be feasible, but most home-based telemonitoring is. Data such as blood pressure, weight and oxygen saturation can be sent over telephone lines, satellite or wireless networks (Circulation 2017;135[7]:e24-e44).

Telemedicine can provide part of the solution, but for now, cardiologists still need to connect with patients in person.

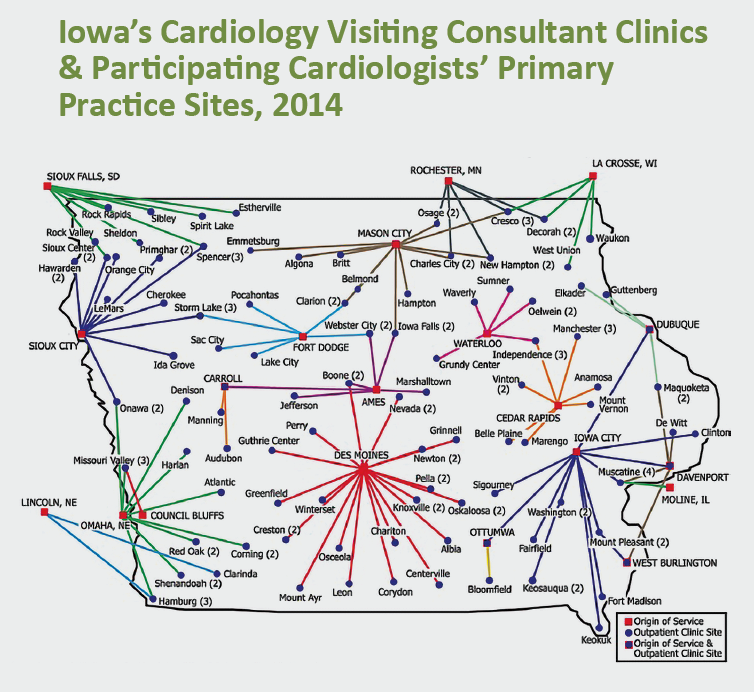

VCCs: monthly road trips

Visiting consultant clinics (VCCs) are clinics in communities—generally rural—too small to support their own cardiologist. Instead, a neighboring cardiologist visits at least once a month. VCCs exist across the country, such as in Iowa, where 89 of the state’s 99 counties are using cardiology VCCs. As a result, more than half of the population’s office visits to cardiologists occur in the patient’s own county (J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5[7]: e002909).

Roughly 45 percent of Iowa’s cardiologists participate in VCCs, according to Thomas S. Gruca, PhD, a professor in the Tippie College of Business at the University of Iowa in Iowa City. As a result, the efforts of 13 full-time equivalent cardiologists have been redistributed from urban-based practices to underserved rural areas, allowing an additional third of the population to live within a 30-minute drive of a location where they can meet, at least monthly, with a cardiologist.

The downside, of course, is the travel. Gruca and his colleagues estimate the opportunity costs due to driving time and direct travel expenses at more than $2.1 million per year. Moreover, the care cardiologists provide in VCC settings is limited compared with that provided by other VCCs, such as oncology and otolaryngology. In cardiology, Gruca points out, most procedures need to take place at larger, better-equipped hospitals.

“The questions you might ask are ‘Why is it that the physicians are doing this? Why are they going out into the country spending all this time meeting with patients?’” Gruca says.

The answer is a mix of clinical and business issues, he explains. “The alternative is to sit in your office and hope people show up.” By meeting patients where they are and establishing the relationship, “you make sure the referrals go to you.” The cardiologists generally respect each other’s turf.

Nevertheless, Gruca’s preliminary assessment of 2017 data suggests the model has limits. For example, fewer cities are being visited (88, down from 96 in 2014). He says the approach “may not be sustainable at the fringes, especially as the physician supply becomes more constrained.” But in general the cardiologist-driven model has worked in Iowa for 30 years. “It’s not the simplest thing in the world to do, but it can be done,” Gruca says. “The question is, ‘Do people have the willingness to go out and try it?’”

A systemized, statewide approach

Joshua Wynne, MD, MBA, MPH, dean of the University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Science, asked a similar question and cardiologists responded enthusiastically.

North Dakota’s approach also demands collaboration. Clinicians have agreed to “rules of engagement” when a cardiovascular patient becomes acutely ill. “What we’ve done for acute patients is to make sure we have a unified approach,” Wynne, a cardiologist, explains. “Then we define care based on how quickly the patient can get to the appropriate facility.”

Patients within a specified radius of a larger hospital are transported for angiography and, if needed, interventions. Those outside the radius receive thrombolytic therapy.

For chronic care, cardiologists work closely with primary care clinicians. Wynne sees his rural patients once, maybe twice, a year. “I really don’t need to see a stable chronic patient with atrial fibrillation and hypertension who is doing well,” he says. “A nurse practitioner probably handles hypertension better than I do. Let me do the stuff I’m good at.”

For this approach to succeed, clinicians across the care team need to work as partners, he emphasizes. To cultivate a spirit of collaboration and support rural workforce development, his university has made rural healthcare a core mission, emphasizing teamwork across disciplines and practice levels. Future nurse practitioners, physicians, nurses, occupational therapists and others work side by side. “From their first days in school we really try to bring them together with other members of the healthcare team for real learning and growing and experience,” he says.

North Dakota’s systematized approach is far from unique, Wynne says, and it’s generalizable in any rural area. As with the VCC model, it does require a shift in thinking. “I don't mean to sound preachy, but while we have a loyalty to our practice or our group or hospital, what really matters is the patient,” he says. “Competition may be fine in the cities, but it doesn’t work well in rural areas.”

Cardiology groups need to agree on a common approach to acute cardiology care, he argues. “Teamwork is critical. Try to get beyond the turf issues. All of us have a place.”