Waiting Games: Competition for Donor Hearts May Encourage Overtreatment

In the U.S., candidates for heart transplantation are prioritized by the intensity of treatment they’ve received, potentially leading some centers to overtreat patients to improve their odds of getting a donor heart.

More than one-third of transplant candidates never receive a donor heart, according to William F. Parker, MD, of the University of Chicago, and colleagues who published a Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC) article on how the supply–demand gap may be driving competition for organs (2018;71[16]:1715-25).

“Status is determined by treatment intensity, based on the premise that candidates nearer death will require escalation of life-sustaining therapies,” the researchers wrote. “There were expected to be relatively few patients waiting at the highest priority ‘Status 1A,’ as these candidates who are receiving the most intense forms of cardiac life-support therapy should have short life expectancies without heart transplantation. However, the proportion of Status 1A candidates has doubled in the past 10 years and now less than 40 percent of candidates wait at this highest priority designation, decreasing the likelihood that lower priority candidates are allocated a donor heart.”

Overtreatment impacts the waitlist—and outcomes

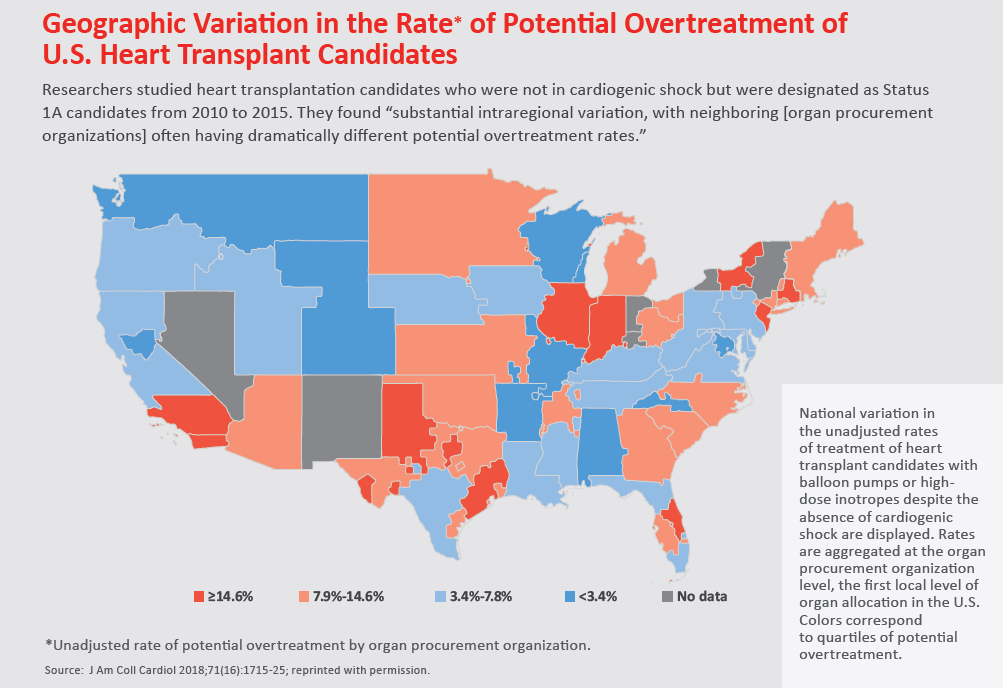

The researchers studied 12,762 adults who were added to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients from 2010 through 2015. They included only individuals who did not meet hemodynamic criteria for cardiogenic shock, thus leaving them open to possible overtreatment with high-dose inotropes or an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP)—two forms of therapy that could bump patients up the waitlist.

Overall, 11.6 percent of patients were potentially overtreated—ranging from 2.1 percent of candidates in centers in the bottom quartile to 27.6 percent in the top quartile. Local competition with two or more centers in the same organ procurement organization was associated with 50 percent greater odds of potential overtreatment. In addition, major urban areas such as New York, Los Angeles and Chicago had high rates of potential overtreatment—further supporting the idea that competition is driving the phenomenon.

“The odds that a candidate was treated with high-dose inotropes or an IABP despite not being in cardiogenic shock was 17.5 times higher in the top quartile of centers than in the bottom quartile,” the authors pointed out. “Accounting for candidate-level differences with either risk standardization or propensity score matching did not reduce the magnitude of the center-level variation. Competitive local organ markets with more centers and higher percentages of top priority Status 1A candidates had higher rates of potential overtreatment.”

The centers that engaged in aggressive treatment of these patients achieved better outcomes. Compared to candidates in bottom-quartile centers, those in the most aggressive treatment centers received donor hearts more quickly (median 146 days vs. 412 days) and had higher survival rates.

“From the perspective of a heart transplantation physician, who is responsible for the care of an individual patient, potential overtreatment can be understood,” Parker and colleagues wrote. “There may be compelling subjective factors, such as severely impaired functional status, which make the use of high-dose inotropes or an IABP appropriate even if the patient is not technically in cardiogenic shock. Furthermore, for an individual patient, the risks of a long wait at lower status may outweigh the harms of overtreatment.”

However, the researchers questioned the ethics of an approach to “game the waitlist” and suggested fairer ways should be identified to distribute donor hearts. Doing so could ensure candidates who need heart transplants the most are more likely to receive them, as well as reduce unnecessary complications from overtreatment.

“We believe therapy-based allocation systems will always be susceptible to manipulation and recommend the development of an objective scoring system for heart allocation,” Parker and coauthors wrote.

New system coming

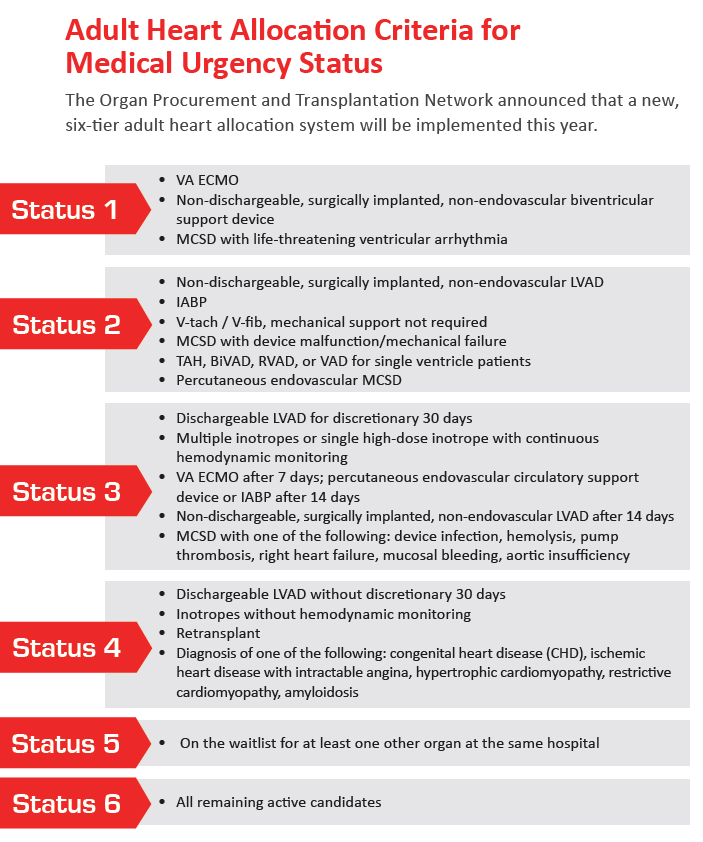

A new era of heart transplant allocation is unfolding, according to Larry A. Allen, MD, MHS, and Prateeti Khazanie, MD, MPH, of the University of Colorado School of Medicine, who wrote a JACC editorial (2018;71[16]:1726-8). In 2018, the United Network for Organ Sharing will begin phasing out the current three-category system (1A, 1B and 2) and implementing a new six-category system (1 to 6). The editorialists say the new system includes “broader geographic sharing of organs across the country for the highest-tier patients, more concrete definitions for [mechanical circulatory support] complications, and objective requirements that patients must meet the American Heart Association hemodynamic criteria for cardiogenic shock to warrant higher listing status.”

They warn that the new system could be manipulated and lead to expensive treatments or tests to bump patients up the waitlist. Some conditions still weigh more heavily into the classification of transplant candidates than others, which could “further exacerbate disparities in care,” Allen and Khanzani wrote.

“The architects of the new allocation plan have the best intentions of solving the disparities created by our current system,” they continued. “They better account for candidate outcomes, provide a more nuanced classification system, and incorporate extensive public and professional input. However, ... fair play is not always natural.

“Clinicians making heart transplant allocation decisions are rarely consciously and flagrantly overtreating patients to outwit, outplay, and outlast one another, but … we all have a ‘personal fudge factor.’ Therefore, we must continue to strive for an explicit and transparent system that ensures optimal fairness, within which clinicians can advocate for individual patients.”