RVUs vs. TVUs: Are Time Value Units a Fairer Way to Measure Productivity?

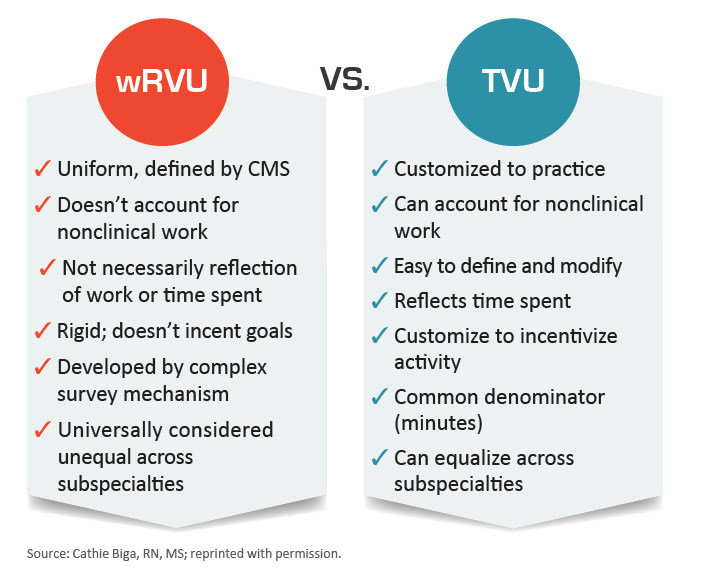

As healthcare shifts from fee-for-service to value-based payment models, practices are experimenting with different ways to measure physicians’ contributions to their practices. Will time value units (TVUs) one day replace relative value units (RVUs)?

A problem with RVUs is implied in the name: Healthcare activities are valued in relation to one another, despite disagreement over how much time or effort they actually take to complete.

To overcome this issue, some cardiovascular practices have begun using TVUs to level the playing field between specialties and better account for non-RVU activities that may still be important to healthcare delivery. While RVUs are used by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for awarding compensation to a medical practice or healthcare system, TVUs may represent a more equitable way to distribute that cash to employees.

The presidents of three practices spoke with Cardiovascular Business about how and why they set up their TVU systems, as well as the sustainability of such systems as the healthcare landscape continues to shift from fee-for-service to value-based payment models.

TVU systems may be more fair than RVUs

In TVU arrangements, every activity commonly performed in the delivery of healthcare is given a value based on how much time it would take the average clinician to complete.

Cardiovascular Management of Illinois and Austin Heart both performed time-motion studies to arrive at these values. They either tracked or surveyed their physicians to determine how much time it took to read a CT scan or perform a catheterization, then averaged those values for each particular task.

It’s not a perfect system, the leaders of these practices acknowledge, and it takes some review and refinement. If a new Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code is added, it must be given a TVU value. Similarly, if improved technologies or procedural techniques are found to reduce the time it takes to perform a task, then the TVU for it must be re-evaluated.

The payoff, however, can be a more collegial work environment where physicians are encouraged to play to their strengths — not pressured to churn out “RVU-rich” activities and procedures.

“As long as people work and they’re contributing to the group, the whole group goes up,” says Norman Risinger, MD, president of Austin Heart, which has 45 to 50 cardiologists spread throughout central Texas. “We’re paid on typically an RVU basis by the health system … so a total volume of RVUs matters but what everybody does individually — as long as they’re working hard — doesn’t matter.

“Everybody does what they like to do,” he adds. “Not everybody has to read echos, not everybody has to read [nuclear imaging studies], not everybody has to do caths, but everybody’s contribution is valued.”

TVU systems allow for the quantification of some important elements to running a practice that RVUs miss, such as leadership, education, marketing, community outreach and travel time. Meeting with a physician to discuss a behavioral issue might be equally or more important than spending an hour in the clinic, Risinger says, but it wouldn’t be captured in an RVU scenario.

Fostering a team approach in cardiology practice

Unlike Austin Heart, Virginia Heart doesn’t award compensation based on TVUs. However, the practice still tracks the time each of its providers spends working to ensure they’re pulling their weight.

Virginia Heart is an “equal-share” practice, says President and Chief Medical Officer Warren Levy, MD, meaning physicians earn the same amount as long as they all fall within 15 percent of the practice’s average TVU output.

“They just like to know that we’re looking at it because it makes people feel comfortable that we’re all working the same,” Levy explains. “Then people aren’t looking over their shoulders, they’re not saying, ‘I’m working harder than this other guy.’”

Even though TVUs aren’t directly tied to compensation in this setup, Levy has noticed his clinicians still like to check in on the TVU values periodically.

“Because docs are so friggin’ competitive … they want to know that they have good TVUs and that they’re working hard enough,” he says. “They don’t want to be the low guy on the list.”

Levy says the combination of the equal-share arrangement and the TVU system has essentially eliminated all of the friction in his practice related to compensation.

“If I see a region where a bunch of the docs are having low TVUs, you need to see what’s going on in the region from a marketing standpoint — are you overstaffed in that region?” Levy explains. “Just as much as if I see a doc who has very high TVUs, I worry about burnout and I worry about why are we expecting this person to do so much — we need to provide them with more help or more resources in that area.”

Healthcare payment models shifting toward quality-based models

With more healthcare payment models shifting toward value and quality, TVUs might represent one way to account for aspects of care that are important to quality but weren’t necessarily lucrative in volume-based systems.

“We have to define different mechanisms to facilitate compensation modeling in the new world,” says Cathie Biga, RN, MS, president and CEO of Cardiovascular Management of Illinois. “I’m not sure this is going to be a perfect way, but it is a measurable way.”

For the two groups under her company’s umbrella, Biga compares both RVUs and TVUs to make sure the gap between the two doesn’t get too wide. That will likely be necessary as long as RVUs are a predominant payment mechanism to health systems. “Be careful that the delta between your RVUs and your TVUs doesn’t become huge, because if you start giving large portions of TVUs to individuals you’re not going to have a compensation model that can cover it,” Biga warns.

Levy says the flexibility of TVUs can allow both health systems and physician practices to quickly pivot to meet the evolving demands of new payment structures.

“I’ve actually argued that it’s a wonderful vehicle to allow health systems to value non–revenue-producing work that becomes important to move from volume to value,” Levy says. “Today, the only way that you can compensate non–revenue–producing work is through quality metrics or certain incentives that go on top of compensation that still tends to be tied to work RVUs. If you use a TVU system you can then decide year to year what is of value in helping you make your goals whether that be at a practice level or a system level.”

Related Cardiology and Radiology RVU content:

VIDEO: The importance of the Physician Practice Information Survey and its impact on radiology reimbursements — Interview with Linda Wilgus, former RBMA president

New metric captures radiologists’ true reporting time for complex cases, potentially enhancing RVUs

Radiology should consider ditching RVUs for a time-based productivity metric, study suggests

Radiologists' on-call workloads have more than doubled relative to ED visits