Balancing Outcomes & Access: Cardiologists Mull TAVR Volume Thresholds, Quality Concerns

As TAVR continues to deliver success for patients and practices, questions about volume and access have emerged.

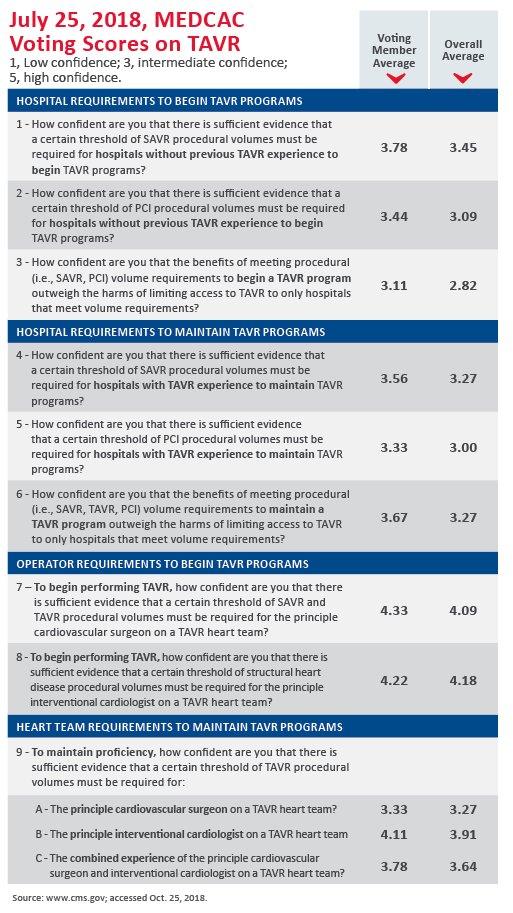

With the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) set to release a new national coverage determination (NCD) for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) in June 2019, researchers at TCT.18 weighed in on what the new procedural volume thresholds should look like.

At the center of the argument is ensuring patients receive reasonable access to the treatment for aortic stenosis while also ensuring there is adequate evidence that centers are performing well enough (and enough procedures) to allow them to continue offering TAVR.

To that point, Joseph E. Bavaria, MD, says, “It is statistically impossible to measure quality at low volumes.”

The current NCD requires centers to perform at least 20 TAVRs annually—or 40 in a two-year span—to maintain an existing program, but a consensus document from several cardiology societies recommended the new NCD bump those minimums up to 50 per year or 100 over two years (J Am Coll Cardiol, online Sept. 28, 2018).

Bavaria, co-chair of the document’s writing committee and a vascular surgeon at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, noted 2016-2017 data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy (TVT) Registry found complication and mortality rates consistently declined as centers gained more TAVR experience. Sites performing 0 to 24 cases annually met a 30-day composite endpoint of major bleeding, major vascular complications and mortality just below 10 percent of the time.

That figure decreased to below 8 percent for sites performing 25 to 49 cases and continued to drop stepwise, finally dipping below 6 percent for centers that performed 200-plus TAVRs. Citing data from both the TVT Registry and other countries, Bavaria says the “number that happens to show up in many analyses is about 50” for achieving the most significant improvements in outcomes, although further gains can be made at higher volumes.

Other presenters at the TCT.18 session on this topic say increasing the annual volume threshold to 50 would decrease access for patients, especially those in underserved communities.

Mark J. Russo, MD, MS, of RWJBarnabus Health in West Orange, N.J., points out there are about 1,100 sites in the U.S. that perform surgical AVR (SAVR) but roughly half perform TAVR. That’s despite TAVR volumes overtaking SAVRs in 2016, with 37,113 TAVRs and 28,037 SAVRs that year, according to data Russo presented.

And there is even evidence that SAVR mortality is greater in SAVR-only centers than those that offer both procedures, Russo says, as one analysis showed a difference of about 2 percent (4.4 percent for TAVR/SAVR centers; 6.7 percent for SAVR-only sites).

Access restrictions

Martin B. Leon, MD, with New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, acknowledges it’s better to have more procedural experience but says compromise is needed to ensure optimal access to TAVR.

Several recent factors may have shrunk the learning curve for TAVR, Leon says. He cites crowd wisdom and group learning to reduce the impact of case experience on group outcomes, new-generation devices that are associated with lower complication rates and standardized procedure protocols.

In many analyses, he points out, the reductions in mortality associated with higher-volume sites are only fractions of a percent. “We think the results are pretty good as is,” Leon says.

Using 2016 data, Leon showed that if the consensus document’s proposed thresholds—50 TAVRs and 30 SAVRs per year—were imposed, 43 percent of TAVR sites wouldn’t meet the minimum requirements. Those sites treated 16 percent of all TAVR patients that year.

“Right now, the NCD is 20 [TAVRs per year]. If you want to increase it to 25, fine,” Leon says. “But when you start increasing it to 50, you begin to potentially exclude sites. … I know how sites behave. I know how our health system works. If you cannot fulfill the NCD requirements in terms of volume numbers that have been published and agreed upon, then you start making arbitrary decisions on how you take care of patients to achieve that level. And that’s not the way we should behave.”

Instead, Leon suggests all efforts be focused on developing quality metrics that can be applied to both high- and low-volume sites. With quality-based rather than volume-based performance measures, Leon says, “we can intelligently … provide both the oversight and remediation that’s needed.”

Serving the underserved

Aaron Horne, MD, MBA, MHS, an interventional cardiologist in North Richland Hills, Texas, and a board member for the Association of Black Cardiologists, voices concern about how TAVR access is often restricted in the African-American population. Blacks represent about 13 percent of the U.S. population but received only 3.8 percent of TAVRs in 2016, according to TVT Registry data.

This finding has multiple causes, reflecting on both the locations of TAVR sites and the cultural differences in black communities, Horne says. He cited data showing that when presented with a 1 percent increased risk of death, 75 percent of blacks would still prefer to be treated in their local center.

“African-Americans are actually refusing access to this therapy when offered it to a greater degree than their Caucasian counterparts,” Horne says. “We also know that African-Americans are less likely to re-access the healthcare system once actually being diagnosed.”

Horne describes a TAVR center he helped open in a predominantly minority area of Dallas that has treated a 30 percent proportion of black patients who have achieved outcomes on par with those of white residents.

A centers of excellence model?

Patrick T. O’Gara, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, has raised the possibility of a hub-and-spoke system for valvular heart disease similar to what’s used in stroke care. This idea of having primary and comprehensive valve centers has been proposed in Europe and successfully piloted in Vancouver.

O’Gara says comprehensive “hub” centers should offer, at minimum, multimodality imaging, TAVR, mitral clip devices, replacements for all heart valves, repair of tricuspid and mitral valves, atrial fibrillation ablation and links with other centers. That final component is important, he notes, to ensure patients receive referrals to the most capable centers when requiring complex interventions.

But another TCT.18 panelist says this approach could lead to the same access issues at play in the argument about volume thresholds. “I think it’s an incredibly privileged view of the world to say that patients can have the wherewithal to travel to centers of excellence,” says Larry L. Wood, MBA, corporate vice president of transcatheter heart valves at Edwards Lifesciences. “I think probably all of us in this room are of that privilege, but not everybody is and I think that’s what [Horne’s] study showed down in Dallas.

“It’s not always about distance,” Wood says. “Sometimes there’s cultural, there’s socioeconomic things. Certainly, by the map you wouldn’t say Dallas needed another TAVR program, yet when [Horne] opened one they treated a lot of patients and a lot of patients who probably weren’t going to be treated otherwise. … I don’t want a TAVR center on every corner, but I want patients to have equal access at getting whatever the appropriate care is for them.”