Worth the wait: After years of trying, researchers 3D print a working heart pump with human cells

A research team at the University of Minnesota spent years trying to 3D print functional heart muscle cells derived from human stem cells—but fell short each time. Finally, however, just as they were ready to give up, two PhD students suggested printing the stem cells first—and it worked.

Those two PhD students, Molly Kupfer and Wei-Han Lin, and the rest of the team wrote about their experience in a study for Circulation Research. Brenda M. Ogle, PhD, head of the department of biomedical engineering at the University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering, was the study’s corresponding author.

“We decided to give it one last try,” Ogle said in a statement. “I couldn’t believe it when we looked at the dish in the lab and saw the whole thing contracting spontaneously and synchronously and able to move fluid.”

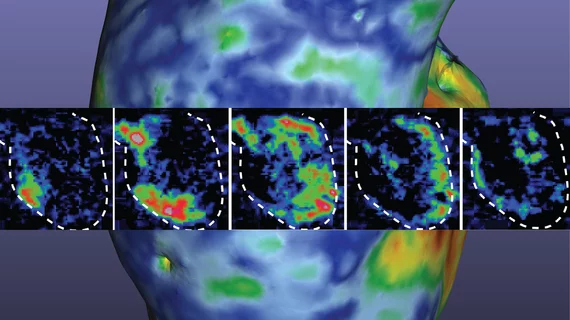

The model sits at approximately 1.5 cm long, a size designed to fit in the abdominal cavity of a mouse. It offers researchers a new way to observe the heart in action, making the team’s years of hard work well worth the wait.

“We now have a model to track and trace what is happening at the cell and molecular level in pump structure that begins to approximate the human heart,” Ogle said in the same statement. “We can introduce disease and damage into the model and then study the effects of medicines and other therapeutics.”

The full analysis is available here.