Cardiologists detail why blood clots are so common among COVID-19 patients

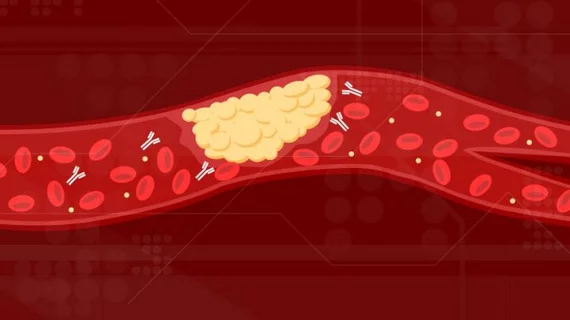

Researchers think they’ve determined why blood clots keep causing so many issues for hospitalized COVID-19 patients, sharing their findings in Science Translational Medicine.

The team’s theory? Antibodies in the blood cause the clots by attacking the patient’s cells, similar to what happens to individuals with antiphospholipid syndrome.

“In patients with COVID-19, we continue to see a relentless, self-amplifying cycle of inflammation and clotting in the body,” co-corresponding author Yogen Kanthi, MD, an assistant professor at the Michigan Medicine Frankel Cardiovascular Center, said in a prepared statement.. “Now we’re learning that autoantibodies could be a culprit in this loop of clotting and inflammation that makes people who were already struggling even sicker.”

Kanthi et al. found that approximately half of the hospitalized patients they studied exhibited both a high level of these antibodies and a high level of super-activated neutrophils. The COVID-19 antibodies and the neutrophils are challenging combination for the body to handle, the team determined using mouse models.

“Antibodies from patients with active COVID-19 infection created a striking amount of clotting in animals—some of the worst clotting we’ve ever seen,” Kanthi said. “We’ve discovered a new mechanism by which patients with COVID-19 may develop blood clots.”

Could blocking or even removing these antibodies make a big impact when treating COVID-19 patients? The researchers aim to find out, noting that plasmapheresis—or another similarly aggressive treatment—could end up being a valid treatment option.