Subclinical leaflet thrombosis after TAVR: What we know, and still need to learn, about a challenging complication

Subclinical leaflet thrombosis is a significant complication associated with transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), impacting up to 15% of patients. But what does it mean for the patient’s long-term health? What is the smartest treatment strategy?

A team of specialists from the Structural Heart and Valve Center at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City explored these very questions in a new analysis for JAMA Cardiology.[1]

“Balancing the competing risks of thrombosis and bleeding is a recurring challenge across contemporary cardiovascular medicine,” wrote first author Thomas J. Cahill, MBBS, DPhil, a specialist with the hospital, and colleagues. “After TAVR, patients face both short- and longer-term thrombotic risks, which must be balanced against the bleeding risks of oral anticoagulation (OAC). Although advances in transcatheter heart valve delivery systems and procedural planning have led to a dramatic reduction in periprocedural complications over the last decade, minimizing both thrombotic and hemorrhagic complications over the medium and long term is a continuing goal toward optimizing patient outcomes after TAVR.”

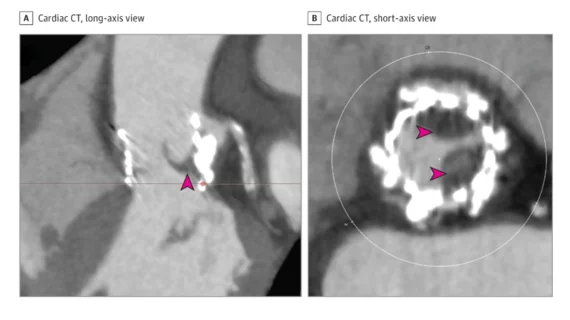

Cahill et al. noted that subclinical leaflet thrombosis is most commonly identified using cardiac CT. It typically manifests to radiologists as hypo-attenuated leaflet thickening (HALT). There’s a risk that subclinical leaflet thrombosis could lead to clinical valve thrombosis, thromboembolism or even structural valve degeneration (SVD), which might lead some specialists to recommend treatment with OAC. However, OAC also comes with its own risks; bleeding events are always a concern, especially among older patients who already undergoing TAVR.

As a result, specialists are left between two options: treat with OAC or don’t treat and accept the relatively low risk of another, more serious complication.

Key research exploring subclinical leaflet thrombosis/hypo-attenuated leaflet thickening after TAVR

This uncertainty, the authors wrote, is one reason low-risk TAVR studies such as the PARTNER 3 clinical trial emphasized the use of cardiac CT. In a PARTNER 3 substudy, for example, HALT was seen in 13% of TAVR patients after 30 days and 5% of surgical aortic valve replacement patients after 30 days.[2] After one year, on the other hand, 56% of patients with HALT at 30 days no longer showed any signs of it. To make things even more confusing, 21% of patients with no HALT at 30 days showed signs of HALT after one year.

The study’s authors noted that the composite outcome of stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA) thrombo-embolism was much more common among aortic valve replacement (SAVR) patients who presented with signs of HALT after 30 days. Clinical valve thrombosis was also much more common—8.6% compared to just 0.3%—among these patients.

The Evolut Low-Risk Leaflet Thickening or Immobility (LTI) substudy, meanwhile, found TAVR with the Evolut valve and SAVR were associated with similar rates of subclinical leaflet thrombosis after 30 days and after one year.[3] Also, the number of clinical events was “extremely low” for both groups of patients.

“Although both studies were underpowered to detect a difference in clinical outcomes associated with leaflet thrombosis, there was a signal for an increase in stroke, TIA, and thromboembolism from the PARTNER 3 substudy,” the authors wrote. “Furthermore, persistent leaflet thrombosis was associated with a slight increase in valve gradients in PARTNER 3. Long-term follow-up of patients will be required to establish the relationship between leaflet thrombosis and valve durability.”

The group also noted that OAC therapy after TAVR has been linked to a lower rate of subclinical leaflet thrombosis. What these studies have failed to show, however, is if OAC actually reduces the risk of thromboembolism or patient mortality. Again, we return to the largest question—do you take on the risks associated with OAC to limit subclinical leaflet thrombosis if you are not gaining any identifiable benefits?

One group’s answer for treating subclinical leaflet thrombosis after TAVR

Cahill et al. detailed their own treatment strategy for subclinical leaflet thrombosis.

“Currently, the evidence base does not support routine cardiac CT for patients after TAVR, or empirical use of OAC for prevention of leaflet thrombosis, in the absence of symptoms or evidence of rising transvalvular gradients on echocardiography, outside of research protocols,” they wrote. “If confirmed, we treat patients with leaflet thrombosis with OAC (preferentially apixaban, rivaroxaban, or warfarin, based on the currently available randomized clinical trial data) for an initial period of three to six months, before reevaluation and a tailored decision about the risks and benefits of ongoing anticoagulation.”

There is presently no data on the ideal dosing strategy for these patients, so the group started with the same dose they use for treating atrial fibrillation thromboprophylaxis.

However, the group noted, this is just one strategy. There are still many unanswered questions about this topic. For instance, how likely is it that subclinical leaflet thrombosis will lead to structural valve degeneration? And how will subclinical leaflet thrombosis impact long-term outcomes?

“Deciphering the long-term clinical significance of leaflet thrombosis and devising studies tailoring OAC to specific patient groups, eg, treatment in those with confirmed persistent leaflet thrombosis, are an important next step toward optimizing outcomes after TAVR and SAVR,” the authors concluded.