TAVR after mitral valve replacement linked to positive outcomes, but heart teams must plan ahead

Performing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) on patients who have a prosthetic mitral valve may be a safe and feasible treatment strategy, according to a new case report published in The Egyptian Heart Journal.[1]

“At present, there are no clear recommendations for this patient subset due to their exclusion from clinical trials,” wrote first author Oyewole A. Kushimo, MBBS, a cardiologist with Max Super-Specialty Hospital in India, and colleagues. “We report our experience of two cases with preexisting prosthetic mechanical mitral valves who underwent TAVR.”

Kushimo et al. highlighted the potential risks associated with this treatment strategy. The two prosthetic valves could interfere with one another, for instance, or TAVR guidewires could cause damage to the mitral valve’s leaflets. There is also a heightened risk of endocarditis or bleeding complications.

The first patient included in this case report was a 57-year-old man who presented with a history of worsening breathlessness and background type 2 diabetes. His mitral valve replacement was 32 years ago, and echocardiography confirmed he had severe aortic stenosis with a mean gradient of 48 mmHg and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 50%. The patient’s prosthetic mitral valve was 6.3 mm below their aortic annular plane.

The operative mortality risk, as determined by a Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk score, was 1.7%.

TAVR was performed under moderate sedation using fluoroscopy and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) guidance. The native aortic valve was crossed with a straight-tip wire and a catheter, which was then exchanged with a pigtail catheter. A guidewire was placed in the patient’s left ventricle over the pigtail catheter. Medtronic’s Evolut R 29 mm TAVR valve was the device of choice. The procedure was a success, and the patient was discharged five days later.

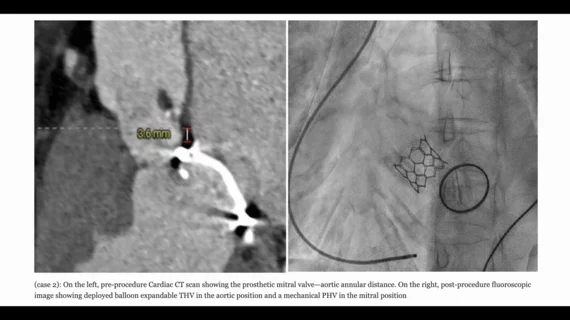

The second patient, meanwhile, was a 66-year-old female with a history of left-sided chest pain. She presented with no history of diabetes or hypertension. She had undergone mitral valve replacement surgery 23 years ago, and an electrocardiogram confirmed she had severe aortic stenosis with a mean gradient of 74 mmHg and a LVEF of 50%. She also presented with non-obstructive coronary artery disease. Her mitral valve was 3.6 mm from her aortic annular plane.

Her STS risk score was 3.5%.

The TAVR procedure was performed under moderate sedation using fluoroscopy guidance. Again, the patient’s native aortic valve was crossed with a straight-tip wire and a catheter, which was exchanged with a pigtail catheter, and then a guidewire was placed in the left ventricle over the pigtail catheter. A balloon-expandable Myval TAVR valve from Meril was the device of choice. The procedure was once again a success. She was discharged after four days, but did require a permanent pacemaker one day after the surgery due to developing complete heart block.

“TAVR seems to be a reasonable alternative for this high-risk population in view of its extensive use and proven efficacy in high- and intermediate-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis,” the authors wrote. “Our experience with the two reported index cases, similar to other reports and registry data included in a recent systematic review, suggests the feasibility of this course of action. Furthermore, it seems the presence of a prosthetic mitral valve may not significantly increase short term mortality risk post-TAVR. However, randomized clinical trial data and guideline recommendations are still lacking.”

The group also emphasized that they encountered no bleeding complications. It was just two cases, of course, but these issues are believed to be more likely among TAVR patients with a prosthetic mitral valve.

Kushimo and colleagues concluded that any heart teams considering this plan of action should carry out “careful pre-procedural planning” using both cardiac CT and TEE imaging. They also wrote that including this patient population in clinical trials could provide additional insights.

Read the full case report here.