X-ray Vision—Building a Hybrid OR: The Plan, Team & Tactics to Do Imaging Right

When North Colorado Medical Center in Greeley set out to build a new hybrid OR equipped with robotic angiography, they had no idea the project would set a new bar for project planning and execution across the health system, bring “exponential improvements” in image quality and “exponential reductions” in radiation dose and contrast media, or that they’d finish the project almost a month early without a single change order and $600,000 under budget. Teamwork, meticulous planning and virtual reality-guidance played an essential role in refining and perfecting this image-guided surgery suite even before a pen was put to paper.

North Colorado Medical Center is a progressive and expanding 223-bed community hospital in a thriving, fast-growing area of Colorado north of Denver. It’s also part of the Banner Health system of 28 hospitals that includes three academic medical centers and other related health entities and services in six states that are known for high tech, quality, safety and outcomes.

The medical center has been serving the multi-state region for 100 years but in 2015 the time had come to add a structural heart program. A year later they brought in Michael Kim, MD, to spark and lead the program that now encompasses a full array of catheter-based valvular interventions including TAVR and MitraClip and non-valvular therapies such as PFO/ASD/VSD closure, paravalvular leak and fistula repair and left atrial appendage closure with the WATCHMAN device. “We wanted to be very aggressive about building this program because there was a huge opportunity in our market and a gap that wasn’t being filled,” says Cardiothoracic Surgeon Maurice Lyons, DO, who has been at the hospital since 2005. They were focused on growth, from a program, market and quality perspective.

To grow, the planning team knew they needed to replace their nine-year-old hybrid OR that utilized an angiography system that lagged in image quality, put out high doses of radiation and lacked dose modulation available on more up-to-date systems.

Kim worked with a team of business managers and administrative leaders over several months to create a financial justification based on the structural heart disease program as a whole, including procedure volumes, potential for growth and drafted a package to get the capital funding. They explored the options: buying a new X-ray system or upgrading their existing unit, in the same room or another site, among a lot of other technology, structural and building considerations. “These are complex rooms, so it takes a well-rounded group of people with different skill sets to get it right,” Kim says.

Banner as a health system has bought into the concept of the hybrid OR equipped with robotic angiography to share and maximize across a variety of surgical specialties with an eye toward improving patient outcomes, expanding patient access with greater flexibility, simplifying procedures, limiting radiation dose to patients and staff as well as infection risk. They expected the new room would allow them to expand services not only in structural heart disease surgeries but also in cardiology and vascular surgery and in the not-to-distant future neurology, urology, spine and trauma. It needed to be future-proof.

“After financially drilling down into every option, we decided that to expand properly we needed a new state-of-the-art OR with cutting edge angiographic equipment to help us offer novel therapies to patients in a safe way,” Kim says. “We discussed the pluses and minuses and even though it would add a bit in cost building in the space next to our old lab, we opted to build there to not disrupt care for our patients.”

Thinking Outside the Box

Step one was planning—which was very different from the start. The 800-square-foot space next to their existing lab was the space available for the new lab. A little tight, but it needed to work. They formed a team of clinical, administrative, financial, architectural, construction and IT experts to carefully map out the equipment selection and installation in the most efficient way in the least amount of time to avoid extra costs.

The design team used lasers and 3D modeling tools, at a cost of $30,000, to map key structural elements behind the walls to know what they had to work around. They brainstormed on the placement of every piece of equipment, display, power outlet, anesthesia machine, patient table and vital personnel in the space which is about 250 square feet smaller and has a lower ceiling height than most hybrid ORs used across the Banner system.

Deciding what was moveable and not, they figured out all the restrictions and what they had to work around, says Senior Construction Project Manager Jim Horiike. “There were a lot, including structural steel, banks of electrical conduits, roof drain lines and sanitary drain lines. We had to work around those, which is why incredibly careful planning was so important.”

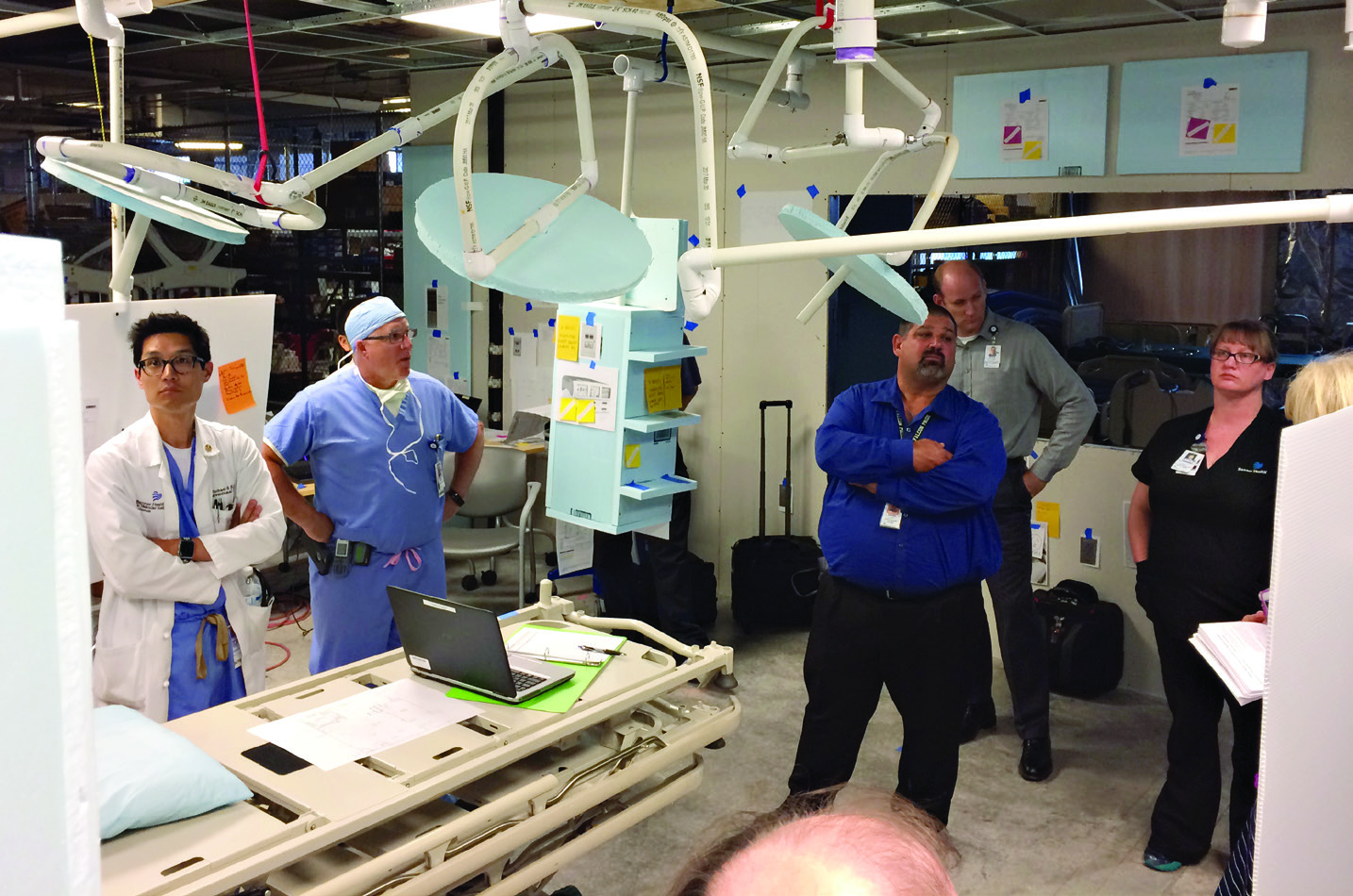

With placement and specific models of the primary equipment configured in the virtual space, the team’s out-of-the-box thinking brought about the idea of creating a mock-up room in shelled space on a different floor with boxes standing in as C-arms, image displays and anesthesia equipment. They built temporary walls and ceiling to the exact size of the space the OR would eventually be built in. Then, using the information from the virtual reality tour, crafted cabinets, heart lung machines, booms and lights out of cardboard, Styrofoam and PVC piping and brought in a patient gurney to represent the operating table.

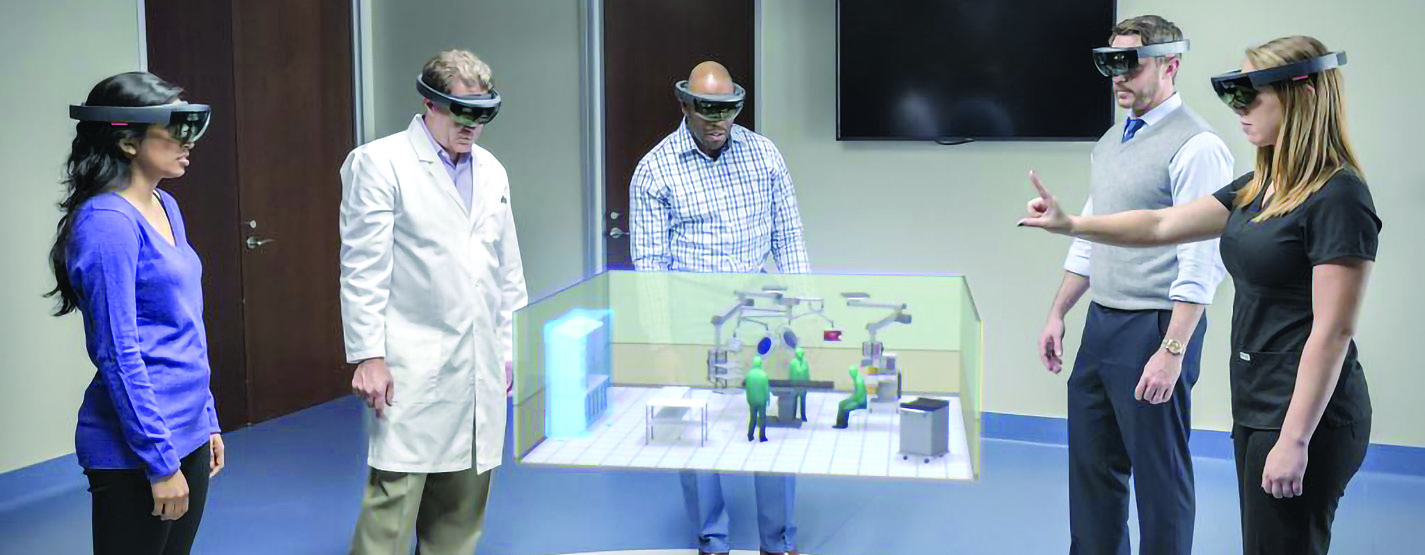

The next step was configuring the space with virtual reality glasses to allow all the stakeholders to “virtually see, feel and touch” the space before it was built. Group after group of key stakeholders including physicians, nurses and techs put on specially designed glasses and visualized the room as it could be built. Together they offered insight, moving things around to perfect the positioning of equipment, people and access.

When it was Kim’s turn, he took one look through the glasses and knew the Siemens Healthineers ARTIS pheno robotic angiography system was the best choice, with Lyons and others nodding in agreement.

They thought a lot about intra-procedure workflow across many clinical specialties. “It allowed us to have the confidence that the room would function the way we needed it to,” says Lyons who was an engineer before becoming a physician. “We worked out the bugs without even putting a screw in the wall.”

“The team members would stand with their mouth open looking around,” recalls Randy Sullivan, MBA, CBET, procedural business operations director. “They offered great suggestions on moving items around and the transformation was amazing. I think all of that went a long ways into both getting buy-in across the team and getting the contents of the room right.”

The team did three rounds of mockups, then left it in place with the exact placement of every detail (down to the sticky note plug-ins and switches on the walls) so the construction crew could reference it as they were building out the hybrid OR.

Getting Serious

The architect took part in all the meetings, mockups and simulations. But she didn’t draw a single line in CAD or on paper, Horiike says. “As soon as that third phase of the mock-up was complete and we said go, she was able to go from zero drawings to 100 percent construction document in about three weeks.”

They analyzed every angle to avoid any change orders or added expense once construction started. About 200 RFIs are typical for a project this size at a cost of about $800 to $1000 each. North Colorado’s goal was zero. “We didn't want anybody to waste time on anything that doesn't add value to the project or to their bottom line,” Horiike says.

With building permit in hand, the general contractor took over constructing the room. Then the equipment vendors installed the equipment. Everything went smoothly, and ahead of schedule.

Only one change was made, swapping out one medical laser for another and 2 hours of an electrician’s time to fix an outlet. “So we did it,” Horiike says. “No change orders or RFIs. From our rough estimate of total cost to our final GMP, we knocked $600,000 off the project. We realized savings because of the careful design and speed of the construction. It went faster because we reduced the overall timeframe, which accounts for about $40,000 a month. No extra work, no unanticipated overtime. And on the front side, we completed all the design work and then put lines on paper. We didn’t pay for any redraws. It all paid off—and changed forever the way we approach projects.”

Building Better Outcomes

Success reaches to the clinical side as well, with the strength of the imaging and system performance convincing Kim to move all of his structural heart procedures over to the new lab.

“What’s so important with the system is TrueFusion software that fuses X-ray and echocardiography together,” he says. “It’s that next step in guiding interventions. So instead of looking back and forth among screens, everything is integrated on one screen that gives me great versatility and reliability. The quality of the imaging is exponentially better and the X-ray dose exponentially lower than we used to have, which is better for patients and operators. I can see that improving outcomes.”

The robotic arm offers great flexibility moving down the table into various positions to accommodate anesthesia, sonographers and nurses, he offers. “To be able to put it at any angle you want to make everyone in the room comfortable is a very unique feature.”

Big reductions in contrast dose to the patient are a big win for Lyons too. “That was very important for patients,” he says. “It’s made a huge difference in the ability to do these operations with an increased safety margin and more confidence that we can put things in the exact spot we need them.” Procedures are a little shorter, too, because physicians can see things more clearly.

There is no doubt robotic angiography is offering greater safety to patients and operators, says Lyons, who offers the example of a patient with a ruptured aortic aneurysm brought in on a helicopter from the eastern plains of Colorado.

“For this patient who was crashing and dying, the technology and design of the room made a huge difference in caring for him,” he says. “Excellent imaging allows us to do very precise intracavity work with really good results. Within 10 to 15 minutes, we had a balloon up and his aorta cross-clamped internally through two-inch incisions and built out his aorta with a couple pieces of endograph. In tough cases like this one is when the best room really matters. Before we had this type of imaging, this patient had an 88 percent of dying from the rupture, by the national average. This allows us to do really complex cases and see things perfectly. The level of patient safety has been enhanced greatly and this patient is doing well and will be home in a day or two.”

Teaming Up

Teamwork in the lab brings good outcomes, and it also makes the difference in project planning. “Because of a great team this project was a success in choosing, building and deploying the best system,” Kim says. “We all recognized that. Everyone had a role, everyone stayed listened to one another and stayed engaged and was dedicated to making sure everything was done right.”

Coming in under budget was a credit to the design team and their creativity “in terms of creating the plan, making sure as many issues as possible could be addressed before they started construction,” Kim says.

Sullivan lauds the team effort too. “Hats off to the design group that recognized early on the best way to build this and make sure people are going to be able to use it well. They were committed to open up the lines of communication to clinicians and everyone involved so it was done right from the very start of planning. They were patient and diligent and did it right every step of the way.”

As Lyons sees it, “every moment this whole team spent planning and doing mockups was valuable. It ultimately led us to creating the most functional space possible to enable the best patient outcomes and completing the project on time and under budget.”

Everybody had a voice and a seat at the table. “We made sure everybody chimed in and got the right people with the right input on the right things,” Sullivan says. “Early on, I remember the architect saying ‘let's make sure we walk before we run.’ The many minds of the team thought it through and together we did it right, covering all the bases before we kicked it into high gear and started building. When we were ready, we ran straight to the finish line and knew we had won based on the feedback from the whole team. Most of all, it was a clinical win so patients will benefit for a very long time.”

Looking forward the team is eyeing growth. “We’re focused on doing more procedures, in structural heart and other clinical areas, and maintaining great outcomes,” Kim says. “For our hospital, a state-of-the-art hybrid operating room was the next step in the natural evolution of programmatic growth. Now that we have it, we want to make sure that more and more of the patients in our community can benefit from it for years to come.”