Q&A: What the impressive durability of self-expanding TAVR valves means for patient care, shared decision-making

Updates about transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) are always big news, but the new five-year data from the CoreValve™ US Pivotal and SURTAVI trials came as a welcome surprise to many cardiologists. It could be a game changer for patients and treatment recommendations of heart teams on surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) vs. TAVR.

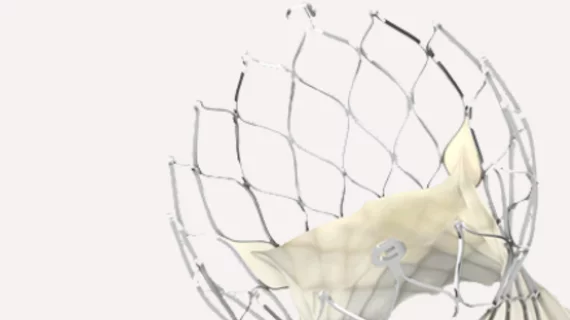

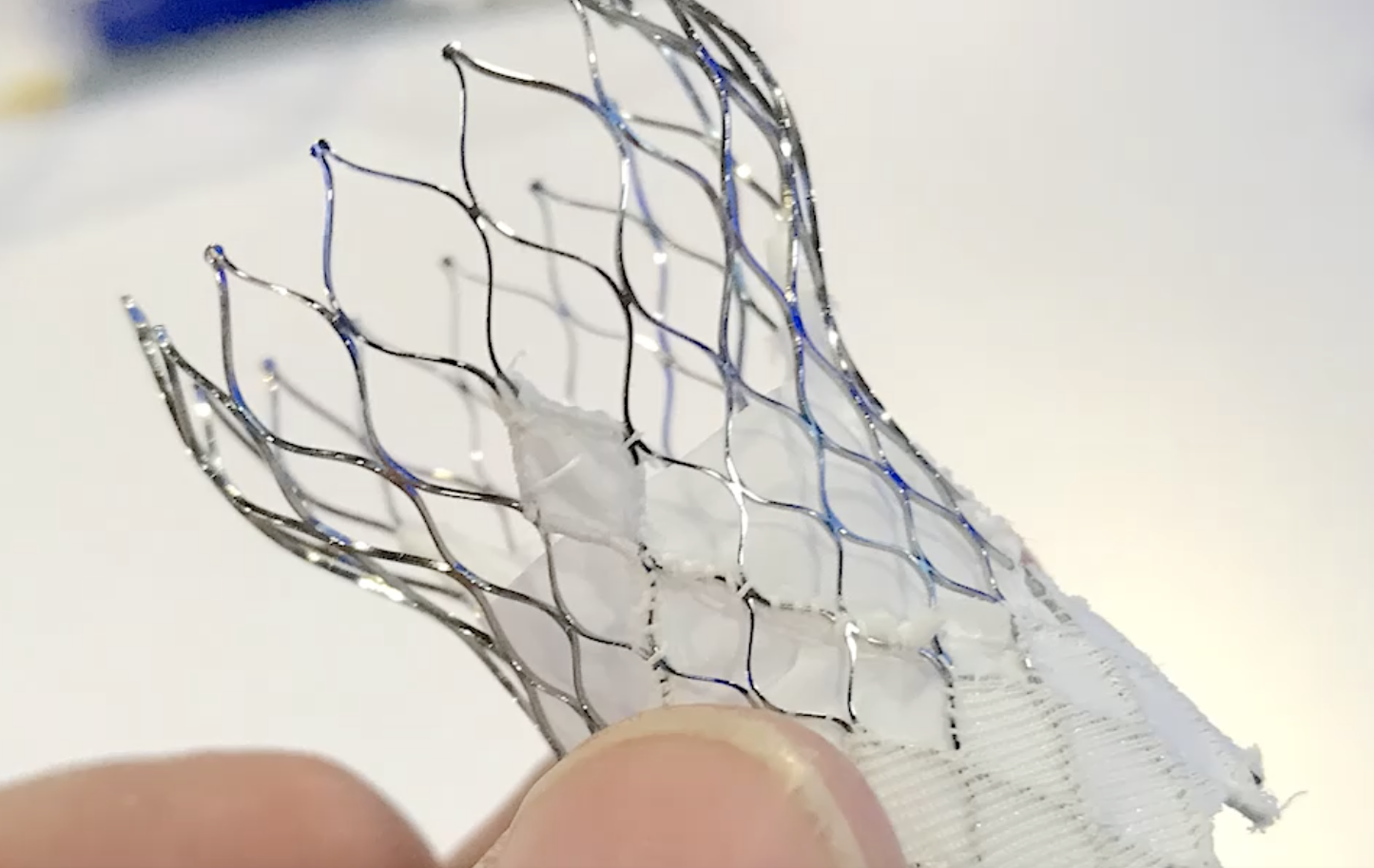

The study assessed incidence, outcomes and predictors of hemodynamic structural valve deterioration (SVD). According to the data, TAVR patients receiving one of the Medtronic (CoreValve or Evolut™) supra-annular, self-expanding heart valves experienced less SVD after five years than patients who received surgical valves. Many within the specialty have remained skeptical about the long-term durability of TAVR valves, but these findings suggest that TAVR may be a more durable option than SAVR.

To learn more about what this means to patients with aortic stenosis and treatment recommendations going forward, Cardiovascular Business sat down with Purvi Parwani, MBBS, MPH, director of the Women’s Cardiovascular Health Clinic at the Loma Linda International Heart Institute and assistant professor of medicine at Loma Linda University Medical Center.

Parwani, a cardiac imaging specialist who regularly confers on the care of patients with severe AS, emphasizes that the updated Pivotal and SURTAVI data are especially exciting due to the potential impact on patient care going forward.

Cardiovascular Business: Can you offer some background on TAVR and why this five-year durability data was so highly anticipated?

Purvi Parwani: We know now that TAVR is an established treatment for severe AS regardless of what the risk may be. In fact, TAVR is now exceeding SAVR in the United States. We are implanting in more and more patients, and risk is no longer at the center of the equation.

What remains a very important question is: what's the durability of these bioprosthetic valves? And that is what this five-year Pivotal and SURTAVI data address.

“We know now that TAVR is an established treatment for severe AS regardless of what the risk may be. In fact, TAVR is now exceeding SAVR in the United States. We are implanting in more and more patients, and risk is no longer at the center of the equation.”

- Purvi Parwani, MBBS, MPH, Director, Women’s Cardiovascular Health Clinic at the Loma Linda International Heart Institute

When it comes to valve durability, which data did the Pivotal and SURTAVI study focus on? What was the biggest takeaway?

The study examined bioprosthetic valve dysfunction, which can include SVD, nonstructural dysfunction, thrombosis or endocarditis. SVD basically indicates wear and tear within the valve—leaflet deformation, any calcification, fibrosis, any of those things. Nonstructural dysfunction, which was also part of the SURTAVI trial, includes such outcomes as paravalvular leak and patient prosthetic mismatch (PPM).

For this specific trial, SVD was defined as an increase in the mean gradient of 10 mm HG or more from the DC/30-day echo compared to the last available echo, and a mean gradient of 20 mm HG at the last available echo or new onset / increase of central aortic regurgitation of greater or equal to moderate in severity. This is where the big news came in: SVD was seen in 2.57% of TAVR patients and 4.38% of SAVR patients. And SVD, we learned, increases a patient’s risk for bad outcomes.

You can see why the industry would be so excited about these findings—it really makes it clear how beneficial TAVR can be for a wide variety of patients.

Was this data what you expected?

No, it really wasn’t. If we think back to just a few years ago, people were still very worried that TAVR may not be as durable as SAVR. That’s what we all thought at the time. There were many concerns that TAVR valves would fail more quickly than SAVR valves. But what this study—the largest study of its kind to date—suggests is actually the exact opposite of that: TAVR valves, particularly the supra-annular, self-expanding valves, have less SVD than surgically implanted valves. TAVR valves are lasting longer in patients of intermediate and high risk. That’s a very important finding.

And it’s not just that we learned SVD is higher with SAVR valves; it’s also the confirmation that deterioration is associated with worse outcomes. The outcomes considered in Pivotal and SURTAVI were all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and hospitalizations for valve-related disease or heart failure, and patients with SVD saw their risk of those outcomes doubled compared to patients without SVD. So this trial clearly showed that SVD, regardless of which valve it is, increases the risk of mortality or hospitalization.

This is all really important, and it’s the kind of information that will be referenced all the time when care teams are considering a patient’s options.

What are the key takeaways from this new data from a patient care perspective?

These supra-annular, self-expanding bioprostheses clearly have a hemodynamic advantage over a surgical valve. This matters to patients when you think about the possibility of implanting TAVR valves in younger patients—say, 65 years old instead of 75 or 80—the question is ultimately going to come up about what will need to be done after the valve has failed.

There has already been a lot of discussion about potentially implanting TAVR valves into younger patients, and these findings suggest that could be an effective strategy. This represents just some of the new information that we can give to our patients. Now we actually know what the valve durability is after five years—and in another five years, we’ll know more about durability after 10 years. This is all a big win for patient care; they always like to know as much as possible about the risks and the long-term possibilities before any procedure.

There also are certain patients who just don’t want open heart surgery, no matter what. Doctors were already excited about TAVR, but the new durability data make it easier when patients don’t want SAVR and TAVR becomes our only real treatment option. It gives us more confidence in the procedure—and longevity of the TAVR valve—when we talk about it with these patients.

How do the new data help you, as someone who refers patients for TAVR, make treatment decisions and offer recommendations? What about heart teams?

Like I said before, a lot of cardiologists have already been wondering about the possibility of implanting TAVR valves into younger patients. Two of the most important things Pivotal and SURTAVI tell us about valve durability are 1.) SVD is associated with worse outcomes and 2.) SVD is worse among SAVR valves than TAVR. With those things in mind, I have to say that I’m much more likely than before to consider recommending a younger patient for TAVR. There’s no question about it. We still have a lot of other things to consider of course, and the risk of reintervention is always present, but Pivotal and SURTAVI have certainly impacted how I feel about implanting TAVR into a younger patient.

The Pivotal and SURTAVI data included a lot of other helpful details as well. SVD had an increased risk among patients who were obese, and among women. And if you’re older or had a history of percutaneous catheter intervention (PCI) or atrial fibrillation (AFib), you had a lower risk of SVD.

Also, the differences between TAVR and SAVR appear to be the most profound when patients are smaller. Among patients with a 23-mm annuli or smaller, SVD was much more likely if you underwent SAVR. That is all very interesting when you think about it.

When you add all of these things together, referring physicians now have much more demographic data to help guide our decisions. With each patient, we can look at their age and all these other factors and consider how many times we may need to intervene on that patient over the course of their life. We need to keep all of these different things in mind, because even though TAVR valves may have this hemodynamic advantage, you have to think about the potential for future interventions. TAVR may now make more sense when treating women, for example, or older patients with no history of PCI or AFib.

Do you have any thoughts about why deterioration may be worse among women?

Even with SAVR, that smaller annulus has always played a key role, so that may be partially responsible. PPM also is more pronounced in women, so that nonstructural deterioration is involved. Considering those things, it did not surprise me that much to see the higher SVD rates with women.

These five-year Pivotal and SURTAVI data seem to have surprised many people in cardiology. Has this shifted your expectations for the 10-year data that we’ll have in another five years?

You’re right that the medical community found these statistics very surprising. While we wanted the durability to be excellent, we were skeptical but proven wrong by this data. It will be interesting to see where those curves go and what exactly happens in another five years. If the 10-year data look good, we may start to spend more time discussing ways to overcome the challenges that are still associated with TAVR, including the higher likelihood of a permanent pacemaker.

Do you have any unanswered questions related to these findings?

We were talking earlier about the possibility of implanting these valves in younger patients—I do think there is still a lot we need to learn about that side of things. All of these bioprosthetic heart valves, the surgical valves and the transcatheter valves, are going to fail eventually. We always have to remember that and consider how many interventions a patient might end up needing in their lifespan.

What if a patient receives one of these valves and then, years later, they need coronary access or TAVR-in-TAVR? What is the feasibility of these things? Right now, the data do not look that great when it comes to those options. But as heart valve durability improves in the future, that could all change.

Do you have any considerations for physicians when it comes to the supra-annular TAVR valves? Anything they should watch out for as they refer patients for these life-changing procedures?

While there is hemodynamic benefit with the supra-annular design, and it is associated with lower mean aortic valve gradients, these patients also tend to have an increased need for pacemaker implantation. While the rates have decreased, this risk remains something to keep in mind when considering treating a younger patient.

See important safety information here