Resurrecting Tc 99m PYP: As Cardiac Amyloidosis Therapies Emerge, an Old Test Gains a New Purpose

Once used to diagnose myocardial infarction, technetium-99m pyrophosphate (Tc 99m PYP) imaging may be reborn as an alternative to biopsy for diagnosing cardiac transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis in some patients. Interest in the test is growing as new therapies show promise in late-stage clinical trials, suggesting possibilities for treating the under-recognized condition.

Clinicians have known about cardiac amyloidosis for several decades. They have understood there are two main types of the disease: cardiac transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis, which is caused by amyloid deposits made up of the TTR protein, and light-chain (AL) amyloidosis, which is an acquired plasma cell disorder.

Patients diagnosed with AL amyloidosis have been able to receive chemotherapy or stem-cell transplantation, both of which could be life-saving. But those diagnosed with ATTR amyloidosis had no treatment options. That limitation, plus the risks associated with performing biopsies on heart tissue to diagnose cardiac amyloid, dampened interest for comprehensive screening for a condition believed to be rare and untreatable. And when ATTR amyloidosis was diagnosed, it tended to be in an advanced stage, with patients surviving only a few years.

Soon, the outcomes for patients with ATTR amyloidosis could significantly improve, thanks to the re-emergence of Tc 99m PYP imaging and the progress of potential new therapies.

“We are at the precipice of a change in paradigm for the treatment of ATTR amyloidosis, with renewed diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities,” says Adam Castaño, MD, MS, a cardiologist and co-director of the Columbia Amyloid Center.

Ronald Witteles, MD, a cardiologist at Stanford University and co-director of the Stanford Amyloid Center, estimates that about a half-million people in the U.S. have ATTR amyloidosis. He acknowledges, however, that 500,000 is just an educated guess and is most likely lower than the actual incidence. As treatments become available and screening protocols are developed, the number will almost certainly increase.

Ronald Witteles, MD, a cardiologist at Stanford University and co-director of the Stanford Amyloid Center, estimates that about a half-million people in the U.S. have ATTR amyloidosis. He acknowledges, however, that 500,000 is just an educated guess and is most likely lower than the actual incidence. As treatments become available and screening protocols are developed, the number will almost certainly increase.

“The point is medical textbooks have conventionally taught that cardiac amyloid is rare,” Castaño says. “Everything we’ve learned over the past decade, however, teaches us that the textbooks are wrong. Amyloid is not rare, and we are rewriting the textbooks.”

Mark Zucker, MD, director of the cardiothoracic transplantation program at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center and RWJBarnabas Health in Newark, N.J., says ATTR amyloidosis is “intellectually one of the most fascinating [diseases] for the simple reason that we now understand the basic physiology of it, we understand the genetics of it and we now understand how to treat it, as well. It’s a huge paradigm shift in terms of our ability to take a disease that was fatal in the past and at least slow its progression.”

Enter: old test, new drugs

An important piece to unlocking the cardiac amyloidosis puzzle came when a few studies found that Tc 99m PYP imaging could be used to determine whether patients had the disease. Until then, the only way to diagnose the disease was with a heart biopsy. However, many hospitals don’t perform heart biopsies, says Zucker, who estimates only five or six of New Jersey’s 70 to 80 hospitals offer the invasive tests. “You needed to find a better way of making this diagnosis [of cardiac amyloidosis], and along comes [Tc 99m PYP],” he says.

Clinicians had used Tc 99m PYP in the 1970s to diagnose myocardial infarction. It fell out of favor in the next two decades, though, due to perceived lack of sensitivity for ATTR amyloidosis “likely because of mixed study populations that included both patients with ATTR and AL amyloidosis,” Castaño says.

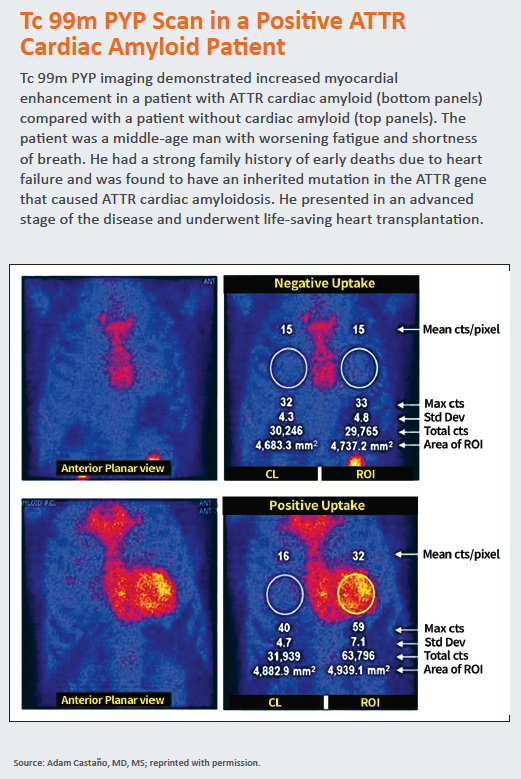

The concept of using Tc 99m PYP to test for cardiac amyloidosis began to garner attention in 2016, when a team from Columbia University examined 171 patients who underwent evaluation for cardiac amyloidosis from 2010 through 2015 at Columbia, the Boston University Amyloidosis Center and the Mayo Clinic. Tc 99m PYP imaging demonstrated 91 percent sensitivity and 92 percent specificity for detecting ATTR amyloidosis (JAMA Cardiol 2016;1[8]:880-9).

The concept of using Tc 99m PYP to test for cardiac amyloidosis began to garner attention in 2016, when a team from Columbia University examined 171 patients who underwent evaluation for cardiac amyloidosis from 2010 through 2015 at Columbia, the Boston University Amyloidosis Center and the Mayo Clinic. Tc 99m PYP imaging demonstrated 91 percent sensitivity and 92 percent specificity for detecting ATTR amyloidosis (JAMA Cardiol 2016;1[8]:880-9).

“In addition, the PYP scan was able to prognosticate disease,” says Castaño, one of the study investigators. “The brighter the heart lit up using the PYP scan, the more advanced the disease and the worse the patient’s survival. Suddenly we had reinvigorated an old cardiac imaging technology that could both diagnose ATTR cardiac amyloidosis accurately and prognosticate the disease. I suppose you can teach an old dog new tricks.”

As those and other results led cardiologists to use Tc 99m PYP more often so, too, did the findings contribute to a greater awareness of the disease in the cardiology community in general. Still, even though physicians finally had an affordable, easy-to-administer test for diagnosing ATTR amyloidosis, there were no FDA-approved medications available. Without treatments to offer patients, the impetus for screening wasn’t there. Experts predict that could change within the next year or two if pharmaceutical companies get FDA approvals for drugs that trials suggest could halt, or even reverse, deposition of amyloid in the heart.

Physicians are eyeing three drugs that have completed late-phase clinical trials: inotersen, an injectable medication from Ionis Pharmaceuticals; patisiran, an infusion product from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals; and tafamidis, an oral medication from Pfizer. Described as TTR silencers, inotersen and patisiran work by suppressing the TTR protein while tafamidis stabilizes the protein.

Inotersen and patisiran could earn an FDA indication for use in patients with the inherited type of ATTR amyloidosis (ATTRmt) as early as late 2018. ATTRmt is caused by a gene mutation and has most commonly been found in African-American, Caribbean and Portuguese populations.

In March, Pfizer announced that tafamidis met the primary endpoint in the phase 3 ATTR-ACT trial. Patients who received tafamidis had a statistically significant reduction in the combination of all-cause mortality and the frequency of cardiovascular-related hospitalizations compared with those who received a placebo after 30 months of follow-up. Further details on that study are expected to be published by the end of 2018. Tafamidis is being tested in patients with the i nherited and noninherited (wild type, or ATTRwt) forms of the disease. ATTRwt type is most often found in older Caucasian males.

“The pharmaceutical companies are thinking, if we can diagnose people earlier [with Tc 99m PYP imaging], we can treat them with a drug earlier and potentially extend their life significantly,” says Frederick Ruberg, MD, director of advanced imaging at Boston Medical Center and associate professor of medicine at Boston University.

(Re)educating clinicians on Tc 99m PYP

As excitement mounts around the new therapies and the opportunity to resurrect Tc 99m PYP imaging, leaders in the field are stressing the importance of educating clinicians about cardiac amyloidosis, whom to screen and how to standardize diagnostic techniques.

“There really has been an explosion of the use of this test,” Witteles says. “It’s certainly a very helpful technology to be able to noninvasively diagnose this disease.”

If the FDA approvals for the new drugs come as experts expect, a number of physicians will be eager to get up to speed on the disease as well as Tc 99m PYP technique and interpretation.

“We want people to understand proper patient selection for the noninvasive diagnosis of ATTR cardiac amyloid using PYP scanning because, in certain cases, a heart biopsy will still be required to get the diagnosis right,” says Castaño.

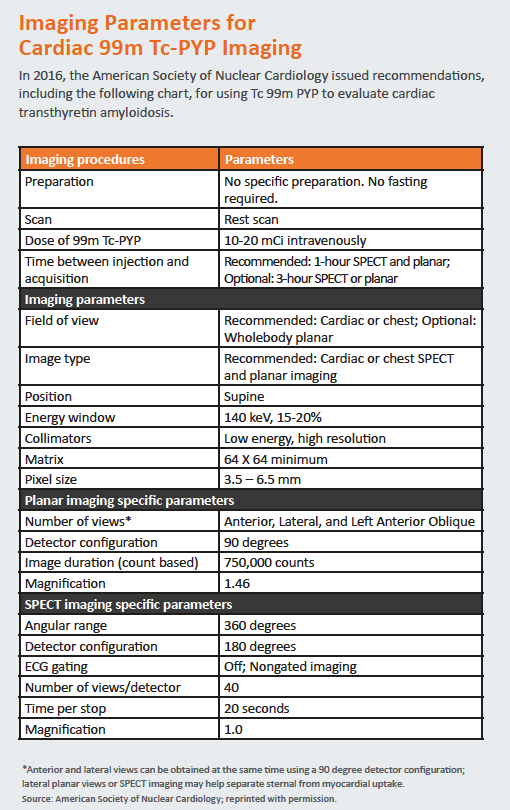

In 2016, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology released “practice points” guidance detailing which patients to image with Tc 99m PYP as well as how to perform, interpret and report findings from the test. The guidance also recommends how to bill Medicare for scans.

“As the technology becomes more widespread, it’s important that we standardize the technique and emphasize how it fits into the diagnostic algorithm for cardiac amyloidosis,” Castaño says.

Research will be essential to continuing the momentum around cardiac amyloidosis, too. At Columbia, Castaño and colleagues are looking at using the scan to measure disease burden and progression. In Boston, Ruberg’s team is studying how Tc 99m PYP might be used in patients with early-stage disease.

“The more we test [Tc 99m PYP imaging], the more we’re going to identify patients with the disease,” Ruberg says. “Now that we potentially have treatments for this disease, it becomes even more important to make the diagnosis early.”