Q&A: Pioneer heart surgeon on the development and long-term potential of robotic aortic valve replacement

Robotic aortic valve replacement (RAVR) is a new minimally invasive treatment option for symptomatic severe aortic stenosis (AS) that uses advanced robotic surgical systems. It has already started gaining momentum as an alternative to both surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) and transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

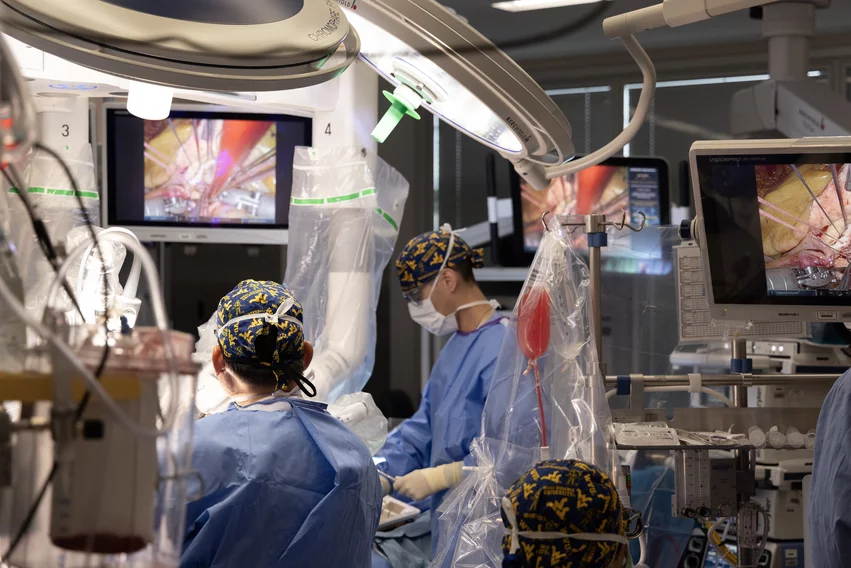

To learn more about RAVR, Cardiovascular Business spoke to Vinay Badhwar, MD, executive chair of the WVU Heart and Vascular Institute and one of the world’s leading voices in robotic heart surgery. Badhwar’s team at WVU developed a RAVR technique that is now being used all over the world, and they hosted an international symposium in November to educate surgeons and cardiologists about the procedure’s potential.

Badhwar, who also chairs the WVU School of Medicine’s department of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery, discussed RAVR’s origin story, compared it to other aortic valve replacement strategies and looked ahead to the procedure’s future.

Read the full discussion below.

Cardiovascular Business: Take me back to the beginning. How did you first get involved with RAVR?

Vinay Badhwar: Starting in 2017, my partners and I started doing cadaver experiments to determine if it was possible to avoid any anterior chest incisions during SAVR. Patients do not want a sternotomy, a mini sternotomy or even the right anterior incision we do during aortic valve operations, but they often do not mind tiny transaxillary incisions.

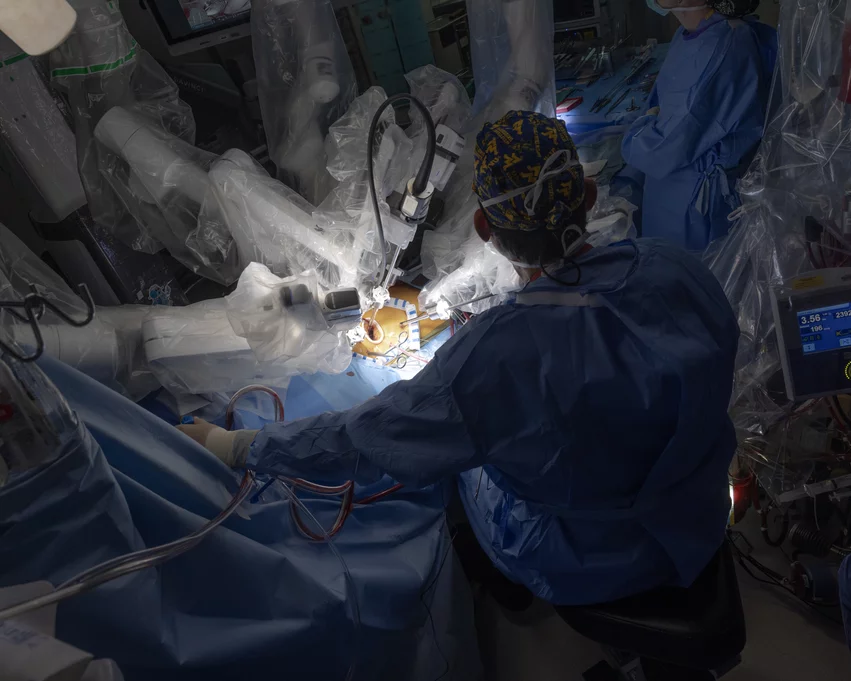

After developing our technique, we defined RAVR as right lateral transaxillary robotic aortic valve replacement. The working incision is three cm in length—exactly what we use for robotic mitral valve operations. At WVU, we have an excellent multidisciplinary collaboration, and it was our structural cardiologists who really encouraged us to move forward. These cardiologists did not want to do TAVR on an otherwise robust, very healthy person with many years of life left, so they helped push us to develop the technique.

After launching the procedure in January 2020 at WVU, we developed a consortium of surgeons around the world. Today there are at least 12 different centers doing RAVR in this way, all using a Da Vinci Xi robot from Intuitive Surgical.

While still early, RAVR appears reproducible; we are approaching 350 consecutive cases with excellent one-year outcomes, including a very low stroke rate.

How does RAVR compare to SAVR and TAVR?

First, I must say that I am an ardent supporter of TAVR, particularly for appropriately selected patients.

SAVR, as you know, involves opening the aorta, resecting all of the aortic valve material and calcium as needed, placing sutures in the annulus and implanting a commercially available bioprosthesis or mechanical prosthesis.

With TAVR, meanwhile, the aortic valve is left in place, which is very different hemodynamically. TAVR valves can work great with excellent gradients, but the hemodynamics in the aortic root are not normal. As we think more about lifetime management in these patients, there could be a lot of derangement in the aortic root. This has been a topic of more recent studies starting to emerge, particularly in younger patients. There have been questions about TAVR for quite some time for these reasons—concerns about cumulative longitudinal stroke risk, for example. Some of those things are starting to come to the fore.

RAVR, though, is identical to SAVR; it is just done robotically, through that small lateral chest incision. No bones are broken, no major muscle groups are distributed, and it can be done in a timely manner similar to SAVR. The position we are taking is, we know the multi-year outcomes related to SAVR—if we are doing the exact same procedure, just robotically, the multi-year outcomes for RAVR should be, at a minimum, the same. So far, our observations are that we were correct, with one exception: We are removing every single bit of calcium now in a way we have never seen before, and this perhaps may be related to the observance of a lower stroke rate.

Regarding the lower stroke rate observed with RAVR, one might recall that in the recent TAVR vs. SAVR trials, SAVR was associated with an initial “penalty” of a potentially higher initial stroke rate; we have not seen that so far with RAVR. The stroke rate has been 2% or less. Also, TAVR is known to have a higher pacemaker rate, but the rate with RAVR has been negligible.

Yes, it is early on for these outcomes, but we believe the augmented precision of RAVR results in very promising outcomes in comparison to SAVR or TAVR.

What makes a patient a good candidate for RAVR?

Patients should be an appropriate surgical candidate for SAVR and a good candidate for peripheral cannulation. At this juncture, if the patient has had multiple prior chest surgeries, it may impact the ability perform RAVR.

We are starting to see patients coming to us because they do not want TAVR. The majority are younger than 75 with the potential for longevity. Also, when our cardiologists identify certain high-risk features such as an elevated calcium score or left ventricular outflow tract calcium that would otherwise be not ideal for TAVR, they prefer to consider RAVR first. So, both patients and providers are seeking RAVR with increasing frequency. This may have relevance to shared decision making as part of the heart team discussion.

What about the costs associated with RAVR? This obviously requires advanced equipment. Could that turn off some hospitals that would otherwise consider it?

Just to be clear, at this point, this is not something we are recommending everyone start doing right away. RAVR should only be performed by surgeons with experience performing robotic cardiac surgery. Mitral valve repair and replacement surgeries are already getting much more common, and teams performing those procedures are likely already going to have the Da Vinci technology that is required. So, really, there is no difference financially, because the hospital already has the equipment on hand; it does not need to be acquired. And we have previously learned that robotic mitral valve surgery is comparable financially to open mitral valve surgery—the same applies here with RAVR and open aortic valve surgery.

It is true that patients are at the hospital a couple extra days with RAVR compared to TAVR. We are definitely not sending anybody home the same day or the next day after RAVR. But when you compare RAVR and SAVR, the length of stay and time recovering from RAVR is much shorter.

What does the future look like for this technology?

I am hoping RAVR may soon be offered in most major centers that already have an existing robotics program within the next five years. Given the current enthusiasm by both surgeons and cardiologists in many institutions and the evidence of reproducibility that we are seeing, I think that with a commitment to consistency and transparency, a wider footprint and access to this technology can be readily achieved.

Any final thoughts?

I want to emphasize again that I am a total fan of TAVR. I want it to continue to succeed. At WVU, I represent an entire heart and vascular institute and service line where transcatheter technologies play a central role. I am a very big supporter of this technology. However, I am even more of a supporter of doing the right thing for the right patient at the right time. It’s all about the evidence and the outcome. Not everything has to be transcatheter. We should just be thoughtful as a physician community who advocate for our patients’ long-term benefit.

Also, like I said earlier, our superb cardiologists have been pushing us forward. Despite being a very busy robotic mitral program and center of excellence for mitral repair, RAVR has already become our most common robotic procedure, and that is with our structuralists leading the way. It is our cardiologists that shifted our institution and state from a TAVR-first mentality to, in many cases, a RAVR-first mentality.

It is still the early days, but I do think this can go on to become one of the many offerings heart teams around the country can offer. If you are considering TAVR in a low- to intermediate-risk patient, perhaps RAVR should be considered as an alternative.