After Shocks: Protocols & Programming Will Be Key to Optimizing ICD Use

Improving the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) will involve discerning appropriate from inappropriate shocks, standardizing post-shock protocols and refining device programming. Following Medicare’s 2018 national coverage determination update, practices may need to evaluate their approach to shared decision-making.

ICDs can save lives. The value of the devices to high-risk patients has long been recognized, as reflected in the practice guidelines, which now recommend ICDs for most patients with decreased ejection fraction, prior ventricular arrhythmias and prevention of sudden cardiac death. That point shouldn’t be lost even as some researchers have turned their focus to the challenges and economic costs associated with ICDs.

Among other issues, they’re studying various impacts of inappropriate shocks—those delivered for non-life-threatening problems, such as electromagnetic interference, a device fault or even supraventricular tachycardias (J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51[14]:1366-8). In a 2017 study, Mintu Turakhia, MD, MAS, associate professor at Stanford University and director of electrophysiology at the VA Palo Alto, and colleagues found that ICD shocks—even inappropriate ones—often result in costly emergency department visits, hospitalizations, tests and invasive procedures (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017;10[2]:e002210).

The research team analyzed the experiences of 10,266 ICD patients between 2008 and 2010. During that period, 963 patients experienced a total of 1,885 shocks. Of those, 38 percent were determined to be inappropriate. Regardless of whether the shock was appropriate, patients often underwent costly invasive cardiac procedures afterward. Overall, 46 percent of shocks led to shock-related healthcare utilization. The mean cost of healthcare following an appropriate shock was $5,592 vs. $4,470 for an inappropriate one.

Many of the costly post-shock interventions had nothing to do with improving outcomes, Turakhia and colleagues found. For example, cardiac catheterization was performed in 76 percent of hospitalized patients, including half of patients with inappropriate shock, yet only 6.6 percent underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. “The low rate of percutaneous coronary intervention suggests that many of the cardiac catheterizations may not have been clinically necessary,” wrote Ryan T. Borne, MD, and Pamela N. Peterson, MD, MPH/MSPH, of the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver, in an editorial. “Yet, patients were exposed to the potential complications of this invasive procedure” (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017;10[2]:e003528).

Turakhia and colleagues suggested that interventions downstream of the shock, rather than the shock itself, could be increasing morbidity. Other researchers note that the shocks themselves are fraught with risk. Each shock likely causes some microscopic damage to the heart, explains Jagmeet P. Singh, MD, ScM, DPhil, deputy editor of JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology and associate chief of cardiology at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Moreover, shocks “can significantly impact the patient’s mental state and quality of life,” Singh told Cardiovascular Business, adding that anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are not uncommon after ICD shocks. In fact, some patients who experience an ICD shock do not adapt well to living with an ICD and become more anxious, sometimes requiring psychosocial interventions (Europace 2003;5[4]:381-9).

Considering programming changes

Considering programming changes

The “main takeaway from our study is not to conclude that ICDs are harmful,” Turakhia stressed in an email to CVB. “Rather, they need to be programmed more intelligently, which for most patients is to adopt a high-specificity approach for what would be ventricular fibrillation or sudden cardiac death if left unimpeded.”

Singh too zeroed in on the need for better programming. “Program the device a little more conservatively … and you may not need to shock the patient,” he says. “Any strategy to limit shocks—appropriate and inappropri-ate—will help to improve outcomes.”

Indeed, the 2012 Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial–Reduce Inappropriate Therapy (MADIT-RIT) study showed that more conservative ICD programming reduced inappropriate shocks and was associated with less all-cause mortality compared to standard programming. In MADIT-RIT, researchers found ICDs programmed to deliver a shock for only those tachyarrhythmias of 200 or more beats per minute had a 79 percent reduction in inappropriate shocks and were associated with a 55 percent drop in all-cause mortality compared to standard programming. Patients with ICDs programmed to delay shock for heartbeats of 170+ beats per minute had a 76 percent reduction in inappropriate shocks and a 44 percent drop in all-cause mortality vs. the usual programming (N Engl J Med 2012;367:2275-83).

Additional research supports these approaches. Allowing arrhythmias to persist longer before the ICD delivers a shock would lead to fewer shocks, according to research published in JAMA in 2013 (8;309[18]:1903-11). And a 2015 study in the Journal of Arrhythmia found that increasing the “intervals to detect,” or NID, reduced unnecessary shocks in ICD patients and potentially lengthened ICD battery life (31[2]:94-100).

Turakhia is less certain about such programming adjustments—at least in the clinic. “When you try to get fancy with trying to intervene on slower or shorter episodes, you do more harm than good—the trials have shown that,” he wrote. “From a public health standpoint, I’m also not sure that in primary prevention patients, we should be giving operators as much latitude to arbitrarily change tachyarrhythmia settings. If MADIT-RIT-equivalent settings are nominally programmed, then perhaps an ‘out of the box’ strategy could lead to better outcomes.”

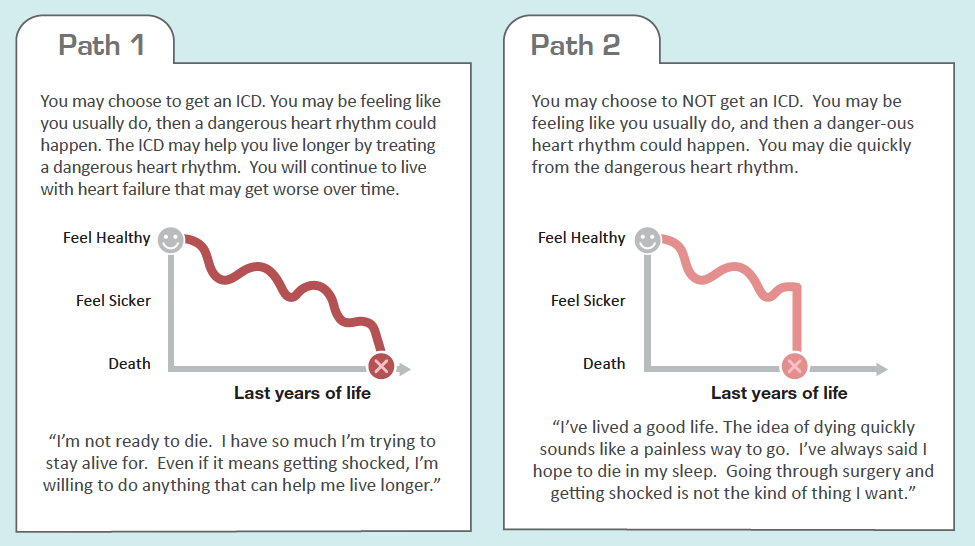

Emphasis on Decision-Support Tools

A University of Colorado School of Medicine decision aid was cited as an example of a tool for shared decision-making in the 2018 national coverage determination for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation. Shown here is an excerpt from the six-page tool, which is available, along with decision aids for other procedures, at https://patientdecisionaid.org/decision-aids.

The debate about device programming reflects the variety of questions about how to refine ICD use. While inappropriate shock rates have declined over the years, how much and whether improvement is continuing are unknowns, Peterson says. “To my knowledge, we don’t have a real-world picture of how devices are being programmed and what real-world shock rates are,” she explains. That’s not due to a lack of information about what works; she notes that evidence-based guidance is available in a multi-society expert consensus document published by Europace in 2016 (18[2]:159-83).

Pushing for post-shock protocols

Peterson points to another challenge: “There’s a lot of variability in what happens when someone receives a shock. There’s no best practice, no care algorithm.”

How aggressive post-shock therapy is may depend on who sees the patient first. For instance, emergency department physicians and primary care physicians may not have the expertise to assess whether a shock was necessary. They may err on the side of caution and routinely admit post-shock patients. “If I were a primary care doc in a small town and my patient received a shock, I think it would be a pretty big deal,” Peterson says.

But often it’s cardiologists who are referring these patients for treatment, says Singh. While he’d like cardiologists to “guard themselves against the unnecessary use of treatment strategies,” he believes the field needs a standard protocol. And that, he says, will require research. It will be essential to study the issue prospectively “so we can develop better clinical algorithms for more patient-specific, individualized approaches to utilization.”