Tool predicts which patients gain the most from ICDs

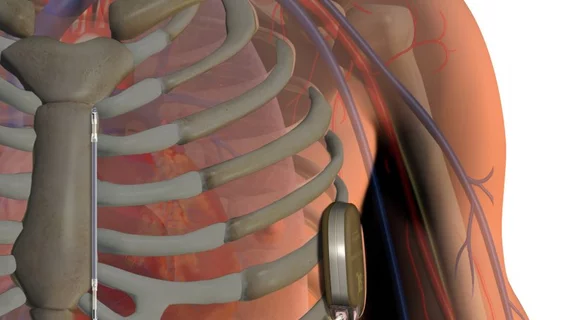

An online tool to help determine which patients might benefit the most from implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) is now available for cardiologists via the University of Washington website.

The tool was also evaluated in a study published June 27 in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology and showed the ability to predict which heart failure patients were more likely to die from sudden death versus other causes.

“We have validated the model with a gold-standard test: applying it to a previous trial in which patients were randomized to an ICD or no ICD—to see if the model would accurately predict, among those who got the device, who would benefit most. And the model worked very well,” lead author Wayne C. Levy, MD, a cardiologist with the UW School of Medicine, said in a press release.

The thinking behind the Seattle Proportional Risk Model goes like this: As the annual risk for all-cause mortality increases, the likelihood that the death will be sudden—or something an ICD could prevent—goes down. Therefore, those with longer life expectancies stand to gain more because their risk of sudden death is relatively higher than individuals who are projected to die soon from other causes.

It has traditionally been difficult to identify “high-benefit” candidates for ICDs. Many patients implanted with the devices never receive an appropriate shock and device-related complications, as well as inappropriate shocks, can lead to rehospitalizations. Less than half of patients with a Class IA guideline indication for ICD therapy receive one, Levy and colleagues pointed out.

Using a randomized trial of 2,521 people with a Class I recommendation for an ICD, the researchers divided patients into quadrants based on their expected all-cause mortality/sudden death rates. Those with the highest risk of death and the lowest proportion of sudden death showed a 10 percent increased risk of mortality with ICD implantation during the median 3.8 years of follow-up, while those on the opposite end of the spectrum showed a 66 percent decrease in all-cause mortality.

Sudden death mortality was reduced by 19 percent with ICDs for the quadrant with the highest risk of all-cause death (but low sudden death) and 95 percent for the quadrant with the lowest risk of death (but highest proportion of sudden death). That’s a five-fold relative increase in ICD benefit based on where a patient falls along the spectrum.

“Modeling these relationships as a continuous function allows us to locate individual patients along a continuum of estimated average benefit, depending on the SPRM-predicted proportion of deaths that are expected to be sudden and potentially responsive to an ICD,” the researchers wrote. “As the ICD-preventable death proportion shrinks, the risk–benefit trade-off becomes less favorable and efficiency/cost effectiveness of treatment with a primary prevention ICD decreases.”

The authors noted the Seattle Heart Failure Model and other risk models are still useful predictors of all-cause mortality that can be factored into shared decision-making on heart failure treatments. But they suggested using the SPRM to weigh that total death risk with the likelihood of benefit from an ICD.

“The SPRM is an evidence-based decision tool that should assist clinicians to go from ‘one size fits all’ recommendations for primary prevention ICD therapy to more patient-centric decisions,” Levy et al. wrote.