‘Failure to rescue’ after PCI: 20% of patients die when complications occur

Major complications are rare during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). According to new data published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions, however, failure to rescue (FTR) is seen in 19.7% of patients when procedural complications do occur.[1]

FTR, the authors explained, is defined as in-hospital mortality following a procedural complication. FTR has been used to track other procedures in recent years, but it has rarely been mentioned in discussions related to PCI.

“While several quality metrics exist for PCI, including in-hospital mortality, appropriateness, proportion of radial access, and door-to-balloon time, FTR has not been evaluated,” wrote first author Jacob A. Doll, MD, with the cardiovascular division at the University of Washington in Seattle, and colleagues. “The existing metrics measure different domains of quality and have inherent limitations. The use of in-hospital mortality, for example, has been questioned as a reliable measure of quality as only a minority of patient deaths after PCI can be directly attributed to the procedure and mortality has been associated with existing patient factors.”

Exploring data from nearly 2.2 million PCI patients

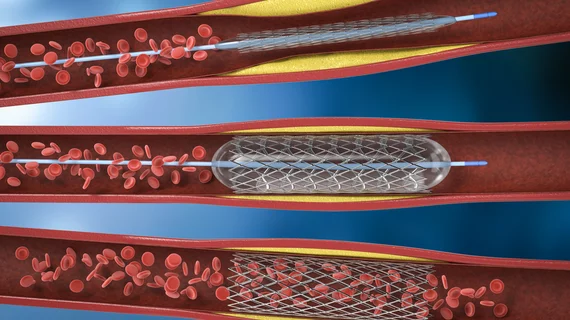

Doll et al. examined patient data from approximately 2.2 million adults who underwent PCI in the United States from April 2018 to June 2021. All data came from the American College of Cardiology’s CathPCI Registry.

Overall, 3.5% of PCI procedures were linked to a complication. The complication rate did not vary significantly over the course of the study, but coronary artery perforation, cardiac tamponade and new cardiogenic shock did become slightly more common from April 2018 to June 2021. Significant dissection and vascular complications, meanwhile, became slightly less common as the study went on.

The study’s overall FTR rate was 19.7%, and it increased from 17.1% in April 2018 to 20.1% in June 2021. FTR was the most common among patients who experienced new onset cardiogenic shock (37.5%), cardiac tamponade (33.1%) and bleeding within 48 hours (18.3%). Other complications linked to high FTR rates included vascular complications (14.4%), coronary artery perforation (12.3%) and significant coronary artery dissection (7%).

The median odds ratio for FTR was 1.48, “indicating significant hospital-level variation.” When looking at specific complications, adjusted odds ratios were highest for new cardiogenic shock (5.31), new tamponade (2.64) and significant bleeding events (1.18).

The authors also noted that certain patient factors were associated with a heightened risk of FTR following PCI complications. These included frailty, diabetes, chronic hemodialysis, cardiomyopathy, multivessel disease and severe calcifications.

Another key takeaway from the group’s research was the fact that hospital factors such as the number of beds were not associated with a heightened risk of FTR following PCI. Meanwhile, as one may expect, “salvage” PCI—also commonly known as rescue PCI—was linked to a much higher risk of FTR than urgent or even emergency PCI.

Researchers did note that the phrase ‘failure to rescue’ may suggest care teams are to be blamed, but this is not the case.

“Even when optimal care is provided, mortality is unavoidable in some cases,” they wrote. “Many patients will die from causes unrelated to the PCI procedure or despite heroic efforts from the cardiovascular team.”

FTR’s significant potential as a quality measure for PCI programs

Doll and colleagues pointed to their findings as proof that FTR data may prove to be a valuable resource for hospitals.

“Our findings suggest that FTR could serve as a novel metric that augments the assessment of PCI quality in addition to existing measures,” the authors wrote. “Current outcome measures such as risk-adjusted mortality have been criticized as unrelated to procedural quality, and have been associated with risk aversion. Furthermore, the process of care measures such as appropriate secondary prevention medications, door-to-door balloon time and documentation of contrast volume are already achieved by most sites and do not explain variation in 30-day outcomes, suggesting limited room for improvement. FTR demonstrated only a modest correlation with hospital-level complication rate and unadjusted in-hospital mortality, indicating that FTR may measure a different domain of care and therefore provide complementary value.”

Click here to read the full study in Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions, an American Heart Association journal.