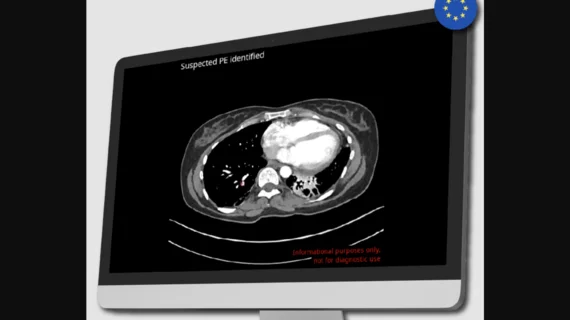

Pulmonary embolism common in patients hospitalized with syncope

A cross-sectional study at 11 hospitals in Italy found that 17.3 percent of patients hospitalized for syncope had pulmonary embolism.

Guidelines from the American Heart Association and the European Society of Cardiology do not have strong recommendations on testing for pulmonary embolism following an episode of syncope, according to the researchers. They added that pulmonary embolism is rarely considered a cause of syncope in part due to the guidelines.

Lead researcher Paolo Prandoni, MD, of the University of Padua in Italy, and colleagues published their results online Oct. 20 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

This study enrolled 560 adults who were at least 18 years old and were hospitalized for their first episode of syncope from March 2012 through October 2014. The mean age was 76 years old, and more than 75 percent of patients were 70 or older. Patients were excluded if they had previous episodes of syncope, were receiving anticoagulation or were pregnant.

The researchers defined syncope as a transient loss of consciousness with rapid onset, short duration (less than a minute) and spontaneous resolution.

Trained physicians interviewed and evaluated patients within 48 hours after they were admitted to a hospital. Physicians also obtained a medical history, asked about pain and swelling in their legs and recorded the presence of risk factors for venous thromboembolism.

In addition, they evaluated patients for the presence of arrhythmias, tachycardia, valvular heart disease, hypotension, autonomic dysfunction, tachypnea and swelling or redness of the legs. Patients also underwent chest radiography, electrocardiography, arterial blood gas testing and routine blood testing.

The researchers ruled out a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism in 58.9 percent of patients due to a low pretest clinical probability of pulmonary embolism and a negative D-dimer assay. The researchers identified pulmonary embolism in 97 of the remaining 230 patients, which amounts to 17.3 percent of the total patient population.

About 25 percent of patients with syncope of undetermined origin and nearly 13 percent of patients with potential alternative explanations for syncope had pulmonary embolism. Patients were more likely to have pulmonary embolism if they had dyspnea, tachycardia, hypotension or clinical signs or symptoms of deep vein thrombosis.

“The unexpectedly high prevalence of pulmonary embolism among our patients with syncope contrasts with that reported elsewhere,” the researchers wrote. “It should be noted, however, that in the few contemporary studies that involved patients presenting with syncope, diagnostic testing for pulmonary embolism was performed only in selected subgroups, which may have resulted in a potential underestimation of the prevalence of this vascular disorder. In contrast, our study involved consecutive patients, all of whom underwent a guidelines-based workup for pulmonary embolism regardless of whether another explanation was suggested clinically.”

The researchers mentioned a few potential limitations of the study, including that they did not include patients who were cared for on an ambulatory basis or patients who visited the emergency department but were not hospitalized. They also noted that it is often difficult to diagnose syncope. In addition, they did not perform diagnostic imaging for pulmonary embolism in all patients and did not confirm deep vein thrombosis in symptomatic patients.