After COAPT: Getting MitraClip Right in the Real World

Will operators be able to replicate COAPT’s restraint & its outcomes?

Not long after the COAPT trial for MitraClip touched off waves of applause from a rapt audience at TCT.18, the conversation took a more sobering twist. How would the field of cardiology ever duplicate the study’s off-the-chart results?

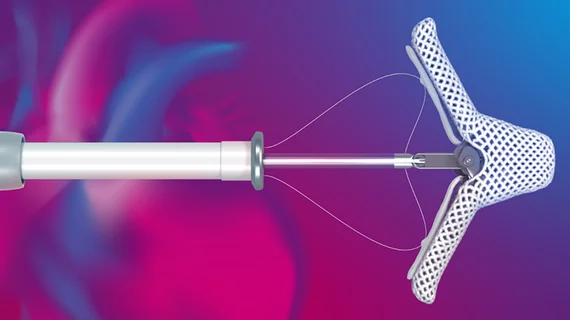

COAPT tapped into the most seasoned MitraClip implanters in the country and enrolled patients with a scrupulousness that limited their number to those most likely to benefit from the tiny device from Abbott that cleverly repairs the mitral valve by clipping its two flaps together. In the real world, however, millions of people in the U.S. with heart failure and mitral regurgitation (MR) are under the care of cardiologists, heart failure specialists and general practitioners with little if any experience identifying the best candidates for MitraClip. Just as questionably, would interventionalists in the heady aftermath of COAPT exercise restraint and implant the device only in the most appropriate patients?

“If our approach is, let there be MitraClip for everyone now that we have access to technology that saves lives and keeps people out of the hospital, that might be a little dangerous and push the envelope too fast,” says Chandan Devireddy, MD, associate professor of medicine and director of the cardiac catheterization lab at Emory University in Atlanta. “We have to first establish some comfort level and experience in knowing how to identify these patients, how to identify the imaging that can guarantee success and then knowing how to drop these clips in a way that will result in a sustained reduction in mitral regurgitation.”

Devireddy is hardly alone in favoring a take-it-slow approach. Sanjay Kaul, MD, a cardiologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, which was the largest enroller of patients in COAPT, finds it hard to reconcile the glaringly different outcomes between COAPT and MITRA-FR, the European-led study of MitraClip in functional MR that earlier found no advantages to the device when weighed against optimal medical therapy (N Engl J Med, online Sept. 23, 2018; N Engl J Med, online Aug 27, 2018).

“Absent any cogent explanations, the logical thing to do is to collect more data to resolve the uncertainties,” he says, casting his lot with the RESHAPE HF 2 trial, which could be unveiled in the next year or two. “What if the FDA expands the indication [for MitraClip] and it turns out to be the wrong decision. Once the genie is out, it’s very difficult to put it back in the bottle. I would argue that what we need is a tie-breaker.”

Many others, however, push back on that notion. “When you have a trial that demonstrates these type of results,” maintains William Abraham, MD, chair of excellence in cardiovascular medicine at Ohio State University and a co-author of COAPT, “they generally translate quite well into clinical practice, and we will see patient improvements that are at least as large or perhaps even better.”

The pathway to those outcomes, he says, can be summed up in two words: patient selection. COAPT clearly demonstrated that the greatest benefits accrue to heart failure patients with moderately severe or severe secondary (functional) mitral regurgitation, also known as grade 3+ or 4+ MR, who did not improve after aggressive treatment with guideline-directed medical therapy, explains Abraham.

Building on a heart team approach after COAPT

In 2013, the FDA approved MitraClip for degenerative mitral valve regurgitation, giving heart failure patients too sick for open heart surgery a potentially life-saving option. It is expected the FDA will now parse the COAPT results to decide if the MitraClip label should be expanded to those with secondary MR, an audience that Abraham estimates could range between 300,000 and 500,000 in the U.S. under the stringent COAPT criteria. Many in the field believe the FDA—which had a strong collaborative hand in designing COAPT—will grant that approval, and that the type of multidisciplinary heart team a pproach used so effectively by COAPT to promote guideline-directed medical therapy as a prerequisite for entry will carry over and circumscribe the use of MitraClip in the messier world of everyday medicine.

“CMS is going to demand it,” says Blase Carabello, MD, professor and chief of the division of cardiology at Brody School of Medicine in Greenville, N.C. “They’re going to be very proscriptive about who they pay for this device.”

Kaul puts it even more bluntly: “I wouldn’t be surprised if CMS imposes tight restrictions for reimbursement to rein in the enthusiasts and to facilitate judicious dissemination.”

There is another model for the heart team approach to patient screening: TAVR. When Edwards Lifesciences rolled out its transcatheter heart valve in 2014, it limited the device to sites that met the highest standards of patient selection and operator training.

“TAVR is really where the value of the heart team for valve disease was demonstrated,” emphasizes Paul Sorajja, MD, chair of the valve science center at Minneapolis Heart Institute. “It was a gatekeeper way of managing who is getting TAVR and was very effective because you had to have not just a cardiologist but two cardiac surgeons agree that TAVR was appropriate for a patient.”

Sorajja fully expects to see the same approach applied to MitraClip once it is approved, with the expectation that the interdisciplinary team at each implantation center would now include a heart failure specialist. Other experts point out the need for an experienced imager on each selection team, given the critical role of these specialists in ensuring the success of the percutaneous clip procedure.

The need for centers of excellence in TEER procedures

Once the FDA gives the expected green light, MitraClip will hardly be starting from square one. There are already an estimated 250 centers around the country, most of them part of or affiliated with medical centers, performing minimally invasive MitraClip procedures on the sickest patients with degenerative MR. (It’s believed an additional 25 percent of procedures are performed off-label on patients with secondary MR in the U.S. In Europe, secondary MR is the most common usage of MitraClip.) How many more implantation sites will be needed to handle the influx of patients, and what professional criteria should interventionalists who perform these procedures be required to meet?

While not venturing a number, Carabello says patients would be best served by limiting the procedure—which reportedly costs around $30,000—to centers of excellence that do between 25 and 50 cases a year. “If you’re an informed patient, you won’t want to go to a center that does just five a year because they won’t have the expertise in imaging or hand skills,” adds Carabello, a member of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology committee that will update the guidelines for valvular heart disease once MitraClip is approved for secondary MR.

Abraham doesn’t feel the technology needs to be restricted to academic medical centers or large community hospitals with structural heart disease programs. “But I do think as we roll it out to newer implanting centers we need to be really careful about implanter training and proctoring and make sure we have the kind of review and oversight” that’s able to replicate the results of the COAPT trial, he insists.

Sorajja, who in the past five years has taught more than 1,000 operators how to implant MitraClip, points out “there is definitely a learning curve,” and that most interventionalists need to do between 10 and 15 procedures to become familiar with the device, and at least two to four a month thereafter to maintain their skills and even improve on them. Abbott, the manufacturer, said through a spokesperson that it will continue to actively train centers and their operators through a defined number of procedures and certification of that training.

As cardiology comes to grips with how to get it right with MitaClip, the supreme irony may be that the system’s success hinges more on the question of who shouldn’t be treated. And that puts guideline-directed medical therapy front and center. To be sure, COAPT investigators turned away many prospective enrollees after learning they had not been maxed out on drugs and cardiac resynchronization therapy, if appropriate.

“It definitely puts more pressure on us to make sure each patient is on guideline-directed medical therapy,” says Devireddy. He cites one recent patient on a downward trajectory who was evaluated for MitraClip and learned all she needed was cardiac resynchronization. “It made the difference between night and day,” he recalls. “The patient got much better and never needed a mitral valve.”