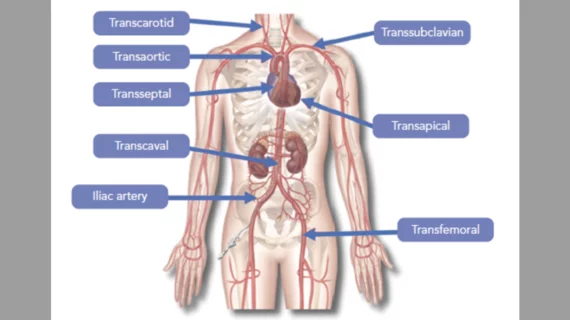

Alternative TAVR techniques: How to proceed when transfemoral access is not recommended

When transfemoral access is not recommended for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), how should cardiologists and the rest of the heart team proceed? A team of researchers from Lausanne University Hospital (LUH) in Switzerland and Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston aimed to find out, sharing their findings in the American Journal of Cardiology.[1]

“Currently, there is no consensus defining the most appropriate approach when transfemoral TAVR is contraindicated, and the choice of the vascular pathway essentially depends on the operators’ experience and the patients’ co-morbidities,” wrote first author Christophe Abellan, MD, a specialist with LUH, and colleagues.

Abellan et al. performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from 18 different studies. Out of nearly 12,000 adult TAVR patients, 57% were treated with intrathoracic access (transapical or transaortic) and the remaining 43% were treated with extrathoracic access (transcarotid, transsubclavian or transaxillary).

Overall, the group found that extrathoracic TAVR was associated with a significantly lower risk of in-hospital all-cause mortality, 30-day all-cause mortality and one-year all-cause mortality. Extrathoracic TAVR was also linked with lower rates of life-threatening bleeding events, 30-day new-onset atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter and 30-day acute kidney injury leading to renal replacement therapy.

One benefit of the extrathoracic techniques, the team noted, was that they are “relatively uncomplicated” due in part to the “superficial location and easy manipulation” of these arteries. Another crucial difference is that that these techniques can be performed under sedation with local anesthesia as opposed to general anesthesia.

Intrathoracic TAVR techniques were associated with certain advantages of their own, the authors added, including lower risks of permanent pacemaker implantation and significant paravalvular leak (PVL).

“It is unclear why patients with intrathoracic access TAVR had a lower risk of developing post-TAVR moderate to severe PVL,” Abellan et al. wrote. “One explanation may be that shorter delivery catheters are used in intrathoracic TAVR because of the smaller distance between the apex or the ascending aorta and the aortic annulus, which may allow better manipulation of the transcatheter heart valve (THV) and its delivery system, in addition to an optimal alignment with the aortic annulus. The type of implanted THV may also play a role. Although both self-expandable and balloon-expandable (BE) THVs can be used with extrathoracic TAVR, only the use of BE THVs has been described with transapical and transaortic approaches because sufficiently short delivery systems exclusively exist with this type of THV.”

The 30-day risk of stroke was not significantly different between the two techniques. This was especially noteworthy when considering extrathoracic TAVR techniques, the researchers explained, because neurovascular complications are a key risk of transcarotid TAVR.

“Our results suggest that extrathoracic TAVR could be considered as the first-line alternative to transfemoral TAVR, with intrathoracic TAVR reserved for patients with unsuitable local anatomy for extrathoracic approaches,” the authors concluded.

Read the full study here.