EP studies during TAVR are safe and effective, new pilot study confirms

Cardiologists can safely perform routine electrophysiology (EP) studies during transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) procedures, according to new research published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.[1]

“The exact mechanism of new conduction disturbances after TAVR remains unclear,” wrote first author Marie-France Poulin, MD, an interventional cardiologist with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, and colleagues. “Previous studies have identified predictors of increased risk, but their accuracy is limited. Direct assessment of cardiac conduction during valve deployment would help understand the precise impact of TAVR.”

Poulin et al. performed a prospective pilot study to learn more, tracking data from 50 consecutive TAVR patients treated at a single high-volume academic center. Patients who presented with permanent pacemakers were excluded. The mean patient age was 80 years old, 46% were women and a transfemoral approach was used in all but one patient; the one exception underwent transcarotid TAVR instead.

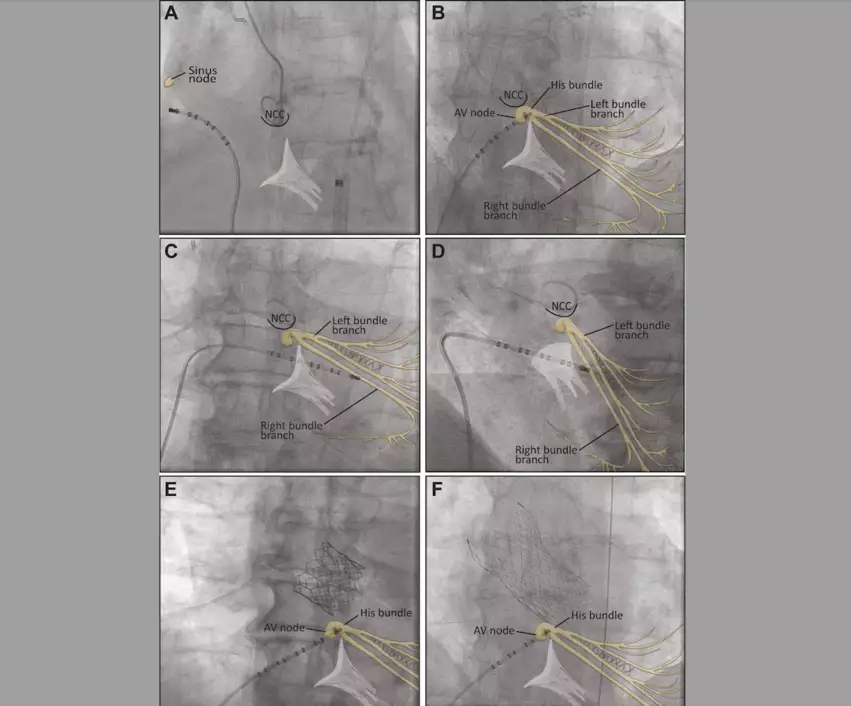

Each patient underwent an EP study before and after valve deployment. The same 6 French multipolar electrode catheter was used for both studies. TAVR operators handled all catheter manipulations themselves, though an electrophysiologist was present in the room to obtain all necessary measurements. A portable EP-TRACER system from Schwarzer Cardiotek was used for all EP studies.

Electrode Catheter Position During Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement for Electrophysiological Study and RV Pacing: (A) Fluoroscopic anteroposterior (AP) view of a decapolar electrode catheter placed in the mid lateral wall of the right atrium during the electrophysiological study. The electrode catheter is then advanced to the His bundle (B), which is located under the noncoronary cusp (NCC) in the same projection. It is then advanced into the right ventricle (RV) for rapid pacing. An optimal position in the midseptal RV wall is shown in an AP projection (C) and in a left anterior oblique 30° projection (D). Image and captions courtesy of JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions and Poulin et al.

Continuous interval monitoring was performed during each study until valve deployment. A temporary pacemaker was used in cases of heart block, “per standard practice.”

Overall, this practice was found to be both safe and feasible. All EP studies were successful.

“Only one case required a temporary pacemaker for rapid pacing because of an inadequate threshold in a hemodynamically unstable patient,” the authors wrote. “Complications were rare: two patients developed new atrial fibrillation attributed to asynchronous pacing. No perforation, pericardial effusion or loss of capture during valve deployment was seen.”

The researchers added that routine EP studies did not make TAVR procedures significantly longer. In addition, TAVR operators quickly caught on to what was needed despite beginning the pilot study with no prior EP study experience.

One key limitation of this study was its small sample size. The authors acknowledged this in their analysis, writing that a larger clinical trial of 400 patients is already underway.

“Incorporating the study in a stepwise approach minimally affects TAVR cases and aids in patient management,” the group concluded. “The information obtained from direct assessment of the conduction system during TAVR will be studied in a large clinical trial.”

Read the full study here.