TAVR embolic protection devices fail to reduce stroke risk, but some cardiologists—and a leading vendor—remain encouraged

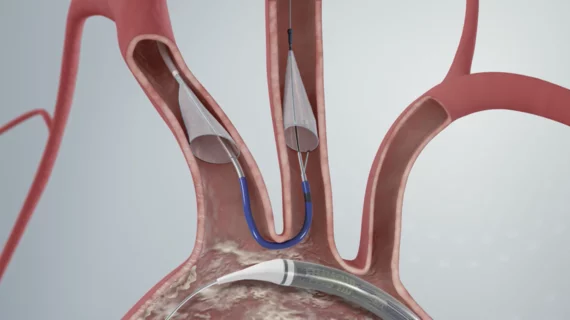

One of the most highly anticipated lat-breaking presentations at the Transcatheter Cardovascular Therapeutics (TCT) 2022 meeting involved the results of the PROTECTED TAVR study. It assessed if the use of cerebral embolic protection (CEP) devices could reduce the risk of stroke during transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) procedures.

Interventional cardiologist Samir Kapadia, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Cleveland Clinic, presented the results in front of a packed crowd Saturday, Sept. 17. His team’s analysis was simultaneously published in full in the New England Journal of Medicine.[1]

Overall, the researchers found, Boston Scientific’s Sentinel Cerebral Protection System was not associated with a significant reduction in the number of periprocedural strokes within 72 hours of TAVR.

Encouraged by their data, Kapadia et al. still concluded that the Sentinel device should be considered for all TAVR patients going forward. Safety does not appear to be a major issue, Kapadia said during his presentation, so the use of these devices may often come down to cost considerations. The study did find that nearly all the embolic protection systems used in the study did capture debris during the procedure that flowed up into the carotid arteries.

A closer look at PROTECTED TAVR

The team’s analysis included 3,000 patients from North America, Europe and Australia. The mean patient age was just shy of 79-years-old, and the mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons surgical risk score was 3.4. All procedure occurred from February 2020 to January 2022.

While 1,501 patients underwent TAVR with the CEP device, the other 1,499 patients did not. The devices were successfully deployed in 94.4% of patients, and they captured debris in 99% of patients. After 72 hours, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality were both 0.5% for CEP patients and 0.3% for control patients. Acute kidney injury was seen in 0.5% of both groups.

Strokes were seen in 2.3% of CEP patients and 2.9% of control patients. Disabling strokes, meanwhile, were seen in 0.5% of CEP patients and 1.3% of control patients, a statistic Kapadia and the panelists on stage focused on at length when discussing the trial. There were no major procedural complications.

Also, the team performed a multivariable analysis, noting that women and patients who received a nonballoon-expandable device were more likely to experience a post-TAVR stroke.

“In this randomized trial involving patients with aortic stenosis undergoing TAVR, the incidence of procedural complications was similar among those who underwent TAVR with or without CEP,” the authors wrote in their analysis. “The use of a CEP device during TAVR did not lead to a significantly lower incidence of periprocedural stroke, but on the basis of the 95% confidence interval around this outcome, the results may not rule out a benefit of CEP during TAVR.”

Boston Scientific funded this study.

Mixed results lead to a mix of interpretations from the PROTECTED TAVR trial

Michael Mack, MD, the medical director of cardiothoracic surgery for Baylor Scott & White Health, was on stage as a panelist when Kapadia reported the results of the PROTECTED TAVR trial. He noted that there is both a positive and a negative reading of these results.

The positive reading, Mack said, is that the CEP device reduced the risk of a disabling stroke and should be in consideration for all TAVR patients. The negative reading, then, is that the CEP device made no impact and should arguably not be considered during any TAVR procedures.

Indeed, to say reactions to this analysis were mixed would be a bit of an understatement. Twitter, for instance, included a wide range of responses, including some commentors who were surprised the disabling stroke statistics were being taken so seriously.

Another key detail when reviewing the reactions to this trial is that all but one panelist on stage said they would want a CEP device to be used if a loved one was undergoing TAVR.

TCT 2022 in Boston featured dozens of late-breaking clinical trials.

“If you put your statistician hat on, maybe you think the reductions weren’t significant enough ... But if you take that hat off and think like a clinician, maybe you think that a 60% reduction in the risk of disabling stroke is pretty meaningful." - Ian Meredith, AM

An executive comments on the results

Cardiovascular Business spoke with Ian Meredith, AM, a veteran cardiologist and Boston Scientific’s executive vice president and global chief medical officer, shortly after the PROTECTED TAVR results were shared with the public. While he and his team were disappointed the Sentinel device was not associated with a more positive impact on stroke outcomes, he also highlighted the reduction in disabling strokes as a major victory.

“If you put your statistician hat on, maybe you think the reductions weren’t significant enough,” Meredith said. “But if you take that hat off and think like a clinician, maybe you think that a 60% reduction in the risk of disabling stroke is pretty meaningful. I spent 10 years doing TAVR before joining Boston Scientific … I remember discussing the risks of the procedure with patients and hearing them say, ‘I can handle the risk of death, I just don’t want to be disabled after this and have someone spoon-feeding me.’”

Meredith was also proud to note that 3,000 patients is a much larger cohort than is normally seen in a structural heart disease trial. Patients are already being recruited for a much larger Boston Scientific-funded study in the U.K., he said.