Healing at Home: Hospital-at-Home Model Takes Care to Patients

In a back-to-the-future move, a decades-old care delivery concept is gaining momentum.

More than 20 years ago, before the triple aim had been enumerated, Bruce Leff, MD, listened when his acutely ill patients refused to be hospitalized. They told him, he recalls, about past experiences in hospitals, where sleep was elusive and rest interrupted. Some believed they suffered functional declines as a result of their hospital stay. Leff, then a medical resident who conducted house-calls for Johns Hopkins University Medical Center in Baltimore, did some digging and found that his patients’ fears weren’t unfounded. Some patients did leave the hospital little better—perhaps even worse off—than when they’d been admitted.

“The development of complications like delirium, muscle weakness, functional impairment and adverse drug reactions often led to patients needing to go to nursing homes instead of returning home,” says Leff, now a professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Leff’s experiences calling on these and other patients in their homes led him and colleagues to develop Hospital at Home, or HaH, where very ill patients who meet certain criteria receive acute care not in the hospital, but in their own homes.

Leff piloted the HaH concept in 1996 with 17 patients who were 65 or older and could have been hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), cellulitis, heart failure exacerbation or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) but instead opted to receive acute care in their homes. Compared with hospitalized patients, the HaH patients had high levels of satisfaction, lower lengths of stay (measured by days in HaH vs. days in hospital) and lower average costs of care (J Am Geriatric Society 1999;47:697-702).

Encouraged by the results, Leff and colleagues expanded the program at Johns Hopkins and conducted a similar study at two Medicare managed care health systems and a Veterans Affairs facility. Patients were initially evaluated in the emergency department. If they refused admission to the hospital, consented to participate in HaH care and were stable enough to go home, they were transferred home and admitted to the HaH program, through which they received hospital-level medical care, including daily clinician visits, medications and oxygen therapy.

The findings again suggested the model was economically and clinically feasible. Overall, 60 percent of patients offered HaH care chose it over in-hospital care. Lengths of stay were shorter (3.2 days vs. 4.9 days for HaH care vs. hospital stays, respectively), and the mean costs were $5,081 for HaH care vs. $7,480 for an in-hospital stay (Ann Intern Med 2005;143:798-808).

A model whose time has come?

Today, as healthcare professionals embrace the goals of better outcomes, more satisfied patients and lower costs, the spotlight is shining on strategies for keeping patients out of the hospital. Since reducing hospitalizations in accordance with patients’ requests is the premise of HaH, it’s not surprising the model is getting traction in a growing number of hospital systems, including Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, Presbyterian Health System in Albuquerque and several Veterans Affairs programs throughout the country.

Meanwhile, in Cardiovascular Disease: A Costly Burden for America, the American Heart Association projected that, by 2035, nearly half of the U.S. population will have some form of cardiovascular disease, generating a price tag of $1.1 trillion. Perhaps HaH’s timing is just right. The question is, would it work in cardiology?

Hearts at home?

To answer the question, it’s important to acknowledge that the recent momentum around HaH has been limited to chronic conditions for which readmissions aren’t uncommon, including heart failure, COPD and community-acquired pneumonia; in fact, there are no HaH programs specific to cardiology. Still, it helps to understand what’s working—and what’s not—in the health systems and hospitals that are trying HaH today.

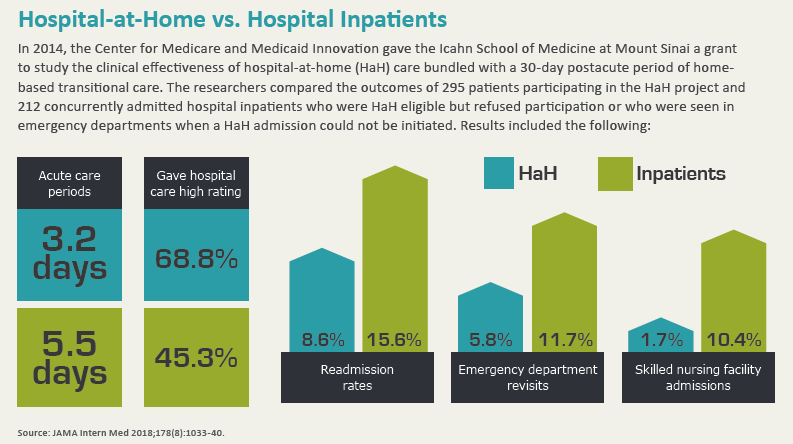

In JAMA Internal Medicine, Albert Siu, MD, MSPH, and colleagues reported their experiences with Mount Sinai at Home, a HaH program launched by the Mount Sinai Health System in 2014 with grant funding from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), which supports research into new payment and service delivery methods (2018;178[8]:1033-40). The researchers followed two groups of acutely ill, HaH-eligible patients: 295 who were enrolled in Mount Sinai’s HaH program vs. 212 hospitalized inpatients.

“Participants presented with medical problems that would otherwise have required hospitalization and, indeed, all of these patients met hospitalization criteria,” explains Siu. As in Leff’s pilot efforts, typical conditions included heart failure or COPD exacerbations, CAP and cellulitis, with patients typically presenting through the emergency department or a primary care office.

Once deemed eligible and enrolled in Mount Sinai at Home, patients received daily visits from both a physician or nurse practitioner and nurses as well as ancillary services, such as physical therapy and phlebotomy. Patients also could connect with physicians, nurse practitioners or nurses via telephone. If problems developed that could no longer be managed at home, patients were transferred to the hospital.

Compared to the hospitalized control group, the HaH patients had lower rates of readmissions (15.6 percent vs. 8.6 percent), emergency department revisits (11.7 percent vs. 5.8 percent) and skilled nursing facility admissions (10.4 percent vs. 1.7 percent). The HaH patients also had shorter acute care periods, averaging 3.2 days vs. 5.5 days for the inpatients. The HaH patients reported lower satisfaction with pain control, which the researchers attributed to an inability to frequently titrate pain medication doses or to patients participating in more physical activity at home.

Siu and other HaH program directors are quick to point out that HaH isn’t appropriate for many heart conditions. The model wouldn’t be safe for cardiac patients whose conditions are unstable or who require intensive care, Siu adds. The HaH models at both Mount Sinai and Presbyterian Health System have excluded patients who need telemetry monitoring because it wouldn’t be feasible for staff to respond to an emergency in time.

Presbyterian at Home Director Nancy Guinn, MD, suggests cardiology programs might consider the model in the context of conditions that tend to require frequent hospital readmissions.

Heart failure is an obvious choice, in part because of readmission statistics. More than 20 percent of heart failure patients are readmitted within 30 days and up to half are readmitted within six months, according to JACC: Heart Failure Editor-in-Chief Christopher O’Connor, MD (2017;5[5]:393).

Leff and Guinn believe the focus on readmission rates might help drive hospital care to patients’ homes but that the real benefit of HaH for heart failure patients is that it could lead to better outcomes.

“You can get echocardiography at home, you can get medications at home, you can diurese at home,” Leff says, also noting that common heart failure treatment regimens such as a low-sodium diet, fluid restrictions and taking daily weights can be optimized in patients’ homes. “Evaluating patients in the home, where you can see them living in the context of their social determinants, really provides tremendous advantages in terms of coming up with treatment plans and approaches that mirror real life.”

Harlan Krumholz, MD, SM, who championed the Hospital 2 Home model, where postacute care services help patients transition from hospital discharge to home without rebounding back to the hospital, says cardiovascular diseases other than heart failure also might be a fit for the HaH model. “I think with stable atrial fibrillation, for example, we can send them home with monitoring and determine how they do,” says Krumholz, a cardiologist and healthcare researcher at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. “With appropriate treatment in the emergency department and follow-up with monitoring, it might be able to be handled at home.”

In some cases, patients with deep vein thromboses might meet the HaH criteria, Krumholz adds. Instead of bringing patients into the hospital for several days of anticoagulation, subcutaneous treatments could be used to bridge some patients to oral anticoagulation.

How-to tips

Developing a HaH program for cardiac patients would require cardiology’s thought-leaders to buy into the program and customize it. It’s a tall order, but there are steps to consider regardless of specialty.

“Pilot and start small,” advises Guinn. “Find a selected population and a champion who is particularly interested in this program. Work with that champion and that selected population, and invest in refining the model and rolling it out.”

Leff recommends reaching out to facilities that have implemented successful HaH programs.

Staffing may present some specific challenges. HaH clinicians need to have experience and skills that make them comfortable in both acute-care and homecare settings.

“The number of physicians who know their way around home-based clinical care is somewhat limited,” Leff says. He notes, however, that expanding telehealth and remote monitoring capabilities could resolve this challenge. “Using a medical home approach, where you have one doctor who can take care of many patients without leaving his or her chair because of remote monitoring, actually helps with some level of getting staff and getting labor to do this.”

Convincing payers

A major hurdle for any service is reimbursement, and HaH still needs to convince payers of the model’s value. Neither Medicare Fee-for-Service nor most private insurers currently cover HaH care, which means that hospital systems implementing HaH need to develop their own payment arrangements with individual payers.

Leff thinks change may be on the horizon. He points to CMMI’s grant support of Mount Sinai at Home as well as signals from commercial entities.

Guinn says the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) may be coming around to seeing HaH’s potential fiscal benefit for costly postacute care episodes that patients often require because of continued debility. She points to CMS’s forays into bundled payments and episodes of care. “They’re discovering that a lot of the expenses are in the postacute care arena of skilled rehabilitation, so by keeping a patient at home and offering care and keeping their functional status, we’re usually able to keep them from having to go to a skilled or nursing or rehabilitation unit.”

Meanwhile, some physicians remain skeptical of HaH. When Siu and colleagues published their Mount Sinai at Home results, Joshua Liao, MD, of the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle, and co-editorialists contributed commentary. Siu’s study, they wrote, “raises several important clinical and policy issues that need to be addressed before HaH programs (and the payment models to support them) could be implemented more broadly. ... Standards and requirements, similar to those that exist for traditional hospitals (eg, Joint Commission accreditation, Medicare Conditions of Participation) currently do not exist for HaH programs and would have to be developed to ensure a minimum standard of care” (JAMA Intern Med 2018;178[8]:1040-1).

The point of HaH is not to replace the hospital, but rather to expand care options for patients, emphasizes Siu. “I think it's every clinician’s experience that there are some patients that would like to avoid hospital stays if they had another option, and this is intended to create another option.”