Playing the Long Game: Connect & Collaborate to Tackle Social Determinants of Health

Addressing social determinants of health improves outcomes, possibly providing a return on investment. Margins matter, but it’s a long game, often driven by a sense of mission.

Over the last decade, healthcare professionals and policymakers have begun paying more attention to the impact of both social needs and social determinants on cardiovascular and other conditions. It’s something many community and thought leaders have long recognized: Poverty and a lack of adequate housing, transportation, healthy food, social connections and so forth are largely responsible for the heath disparities seen across race and socioeconomic groups in the U.S.

Disparities account for roughly $93 billion in excess medical care costs and $42 billion in lost productivity per year, plus there are economic losses associated with premature deaths, according to a 2018 brief by the Kaiser Family Foundation. An American College of Physicians position paper estimates that “population-level inequalities in health care result in $309 billion in losses to the economy annually and disproportionately affect disadvantaged populations” (Ann Intern Med 2018;168[8]:577-8).

Hospitals and health systems are not equipped to heal these disparities, let alone their root causes, so they are increasingly turning to their communities. As margins tighten and healthcare organizations are forced to make do with less, guiding patients to non-medical resources makes sense, whether the focus is prevention, management or recovery.

ENGAGEMENT VS. BURNOUT

Most physicians recognize the toll of social determinants on patient health but, according to a 2018 paper from Leavitt Partners, they tend to consider such issues to be outside their purview. For example, 66 percent of surveyed physicians thought help with transportation would benefit their patients, but roughly the same proportion (69 percent) indicated neither doctors nor insurers are responsible for providing such assistance.

It may seem cold at first, but consider: What resources does the average cardiologist have to provide low-cost patient transportation options?

In a world “where the next straw is the last straw,” the solution is to make sure physicians know how to make an impact—and that they have the tools to do just that, says Thomas Mahoney, MD, chief medical officer of Common Ground Health, a nonprofit regional collaborative based in Rochester, N.Y.

Research from 2018 suggests burnout increases when physicians don’t think their organization can address patients’ social needs (J Health Care Poor Underserved 2018;29[1]:415-29). The research was specific to primary care, but the implications apply to other specialties: Having the resources to help patients may be a way to address clinician burnout.

Leveraging outside resources could start as simply as learning where to refer patients for support. For ex-ample, knowing how to write a “fresh food” prescription empowers the clinician while helping the patient.

All of this aligns with one conclusion from the Leavitt Partners report: Strategies to address social determinants of health in clinical settings must not increase the burdens on physicians. Instead, strategies should reflect the goal of reducing the challenges that both patients and clinicians face.

Fortunately, resources often are available. They don’t need to be developed; they need to be tapped.

SOMETIMES, A HAIRCUT ISN’T JUST A HAIRCUT

Ensuring the workload doesn’t fall heavily on physicians means leveraging community resources. There’s no need to reinvent the wheel, but being where people live, work, play and pray is crucial.

Often, the providers who make the biggest difference on the ground are community health workers. Generally, these are individuals with no formal medical training who connect fellow community members to services and help them make lifestyle changes to improve health. They can work anywhere, including, for example, in barbershops.

In ages past, barbers often were the healthcare providers of necessity. Today, some barbers are playing a growing role in preventing and managing hypertension and supporting cardiovascular health, especially in African-American communities.

Like similar programs, Common Ground Health’s Rochester High Blood Pressure Collaborative enlists barbers and beauticians in its campaign for better cardiovascular health. The intervention is backed by evidence. For example, a 2010 study found that African-American men with hypertension who received health education and monitoring from their barbers achieved better blood pressure control compared to a control group that simply received conventional blood pressure pamphlets (Arch Intern Med 2011;171[4]:342-50). And a 2018 study found hypertension management was better among African-American men whose barbershops hosted meetings with specialty pharmacists who were permitted to prescribe medications vs. a control group whose barbers merely encouraged lifestyle modifications and doctor appointments (N Engl J Med 2018;378:1291-1301).

Church, a center of community life in many underserved neighborhoods, also presents opportunities to address social needs. Fifteen years ago, a study published in the American Journal of Public Health concluded that faith-based programs can improve health outcomes (2004;94[6]:1030-6). In keeping with that finding, the Rochester collaborative partners with the Interdenominational Health Ministry Coalition on Healthy Blood Pressure through Faith and Lifestyle, which provides health education and targeted lifestyle interventions.

It’s about being in the community: That’s a crucial lesson from the Rochester collaborative, Mahoney says. Initially community health workers were deployed in physicians’ office to counsel patients about hypertension, but they were far less effective than those in the field.

Much still happens in the clinic, however.

PHYSICIAN-LED SAN DIEGO EFFORT

PHYSICIAN-LED SAN DIEGO EFFORT

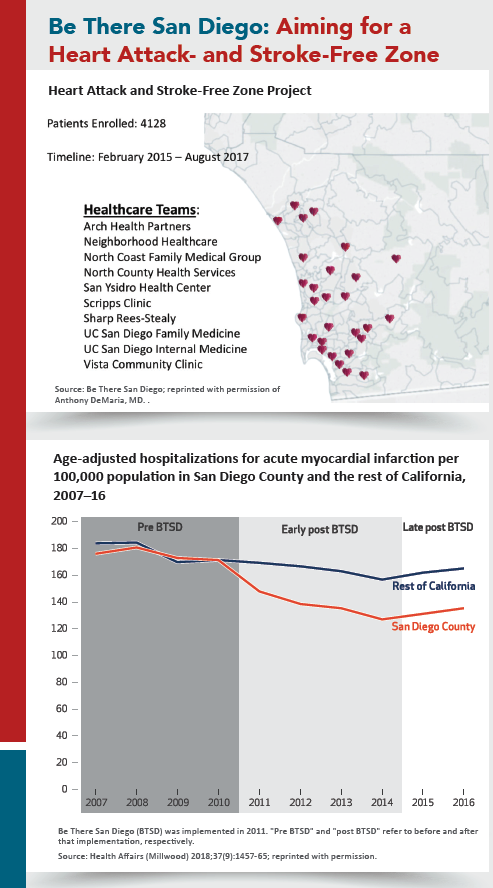

In 2010, the Be There San Diego collaborative set the “audacious” goal of eliminating heart attacks and strokes in the region through the spread of best practices and patient and medical community activation.

The results have been significant, as documented in Health Affairs (2018;37[9]:1457-65). Heart attack hospitalization rates decreased by 22 percent in San Diego County vs. 8 percent in the rest of California, with an estimated 3,826 hospitalizations avoided and $85.8 million saved between the program’s 2011 launch and 2016.

Be There San Diego puts community health workers on patient care teams, partners with pharmacists and faith organizations, and develops easy-to-use recommendations for healthcare teams. Physicians meet regularly with various agencies and community groups to learn about resources for their patients. They also share best practices and practice data among themselves. “Collaboration among competitors—that’s our secret sauce,” says Anthony DeMaria, MD, who chairs Be There San Diego and is chair of cardiology at the University of California-San Diego.

Another reason for both the buy-in and the sustained involvement in the initiative is that “it didn’t come from deans of the medical school or the hospital administrators or the heads of the health system,” DeMaria notes. “It was the practicing doctors.”

PLUGGING IN

Some efforts benefit from physician leadership. For example, DeMaria thinks Be There San Diego works in part because “virtually all” of the area’s doctors participate. Bringing everyone to the table proved challenging, he acknowledges. “The first step is the hardest,” he says. But, once they see the benefit, “the sentiment is, ‘You know, I’m happy to participate in this because I think it’s good for my patients and it’s good for my community.’”

Still, cardiologists don’t have to serve in the trenches to be part of the solution. What's important is that they play an active role in connecting patients to resources that will bridge care from their exam rooms, labs and operating suites to the community.

“The cardiovascular specialist, no matter how sub-specialized, needs to make sure there is an umbrella environment that takes care of the patient,” says Michael R. Jaff, DO, a vascular medicine specialist and president of Newton-Wellesley Hospital, a 313-bed, Partners-affiliated hospital in Massachusetts.

‘THIS STUFF MATTERS’

Jaff launched Newton-Wellesley’s Collaborative for Healthy Families and Communities (CHF&C) in 2018 to build on and pull together the hospital’s existing efforts. It currently focuses on child and adolescent mental health, postpartum depression, palliative care, domestic violence and elder services.

The hospital also has a substance abuse program that offers addiction and recovery coaches and through CHF&C, provides naloxone to local first-responders. “Things that communities would never be able to afford, we provide,” Jaff says.

Ask Jaff what CHF&C has to do with cardiologists, and his answer is succinct: “Absolutely everything.” A cardiologist may perform the most sophisticated procedures imaginable, but once the procedure is over, if the system can’t support those patients in their lives at home, “the cardiologist’s work can be for naught,” Jaff explains. “It could fail because the patients may not have enough food to eat. They may not be able to heat their home. They could become depressed. They could be at risk for abuse. They could become dependent on opioids.”

There’s the downstream aspect as well. Individuals who have mental health disorders, including those who struggle with addiction, often are at accelerated risk for cardiovascular events later in life because their cardiovascular risks were not effectively managed.

“This stuff matters,” Jaff insists, adding that he is planning to add to the CHF&C menu a program aimed at raising awareness of lifestyle as a contributor to cardiovascular risk.

MAKING HOME HABITABLE

Transitions are particularly precarious for at-risk patients. Newton-Wellesley works with families, partners with various agencies, coordinates with public health agencies and enlists Partners Continuing Care to ensure that, after inpatient or emergency department discharge, patients—especially the frail—don’t languish alone in empty homes.

Inpatient discharge planning begins days in advance. A partnership with Lyft helps with transportation. A simple home check to ensure there’s heat when it’s cold, food in the cupboard and the right prescriptions in the cabinet can spell the difference between recovery and a readmission. Community partners can step in to connect patients with the services they need.

That’s important even beyond ensuring a safe environment: A 2016 meta-analysis concluded loneliness and social isolation are risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke (Heart 2016;102[13]:1009-16).

MedStar Health’s three Baltimore hospitals have community health workers in their heart failure units who work with patients at high risk for readmissions. The community health workers regularly conduct home visits as part of 30-day follow-up. The vis-its provide insights into the patients’ needs with no additional burden on the cardiologists or their teams, says Ryan Moran, MHSA, MedStar Health’s director of community health, Baltimore City.

Community health workers focus on patients who have an estimated readmission risk of 22 to 24 percent, where the readmissions rate is consistently 11 percent. “That is pretty profound in terms of cost of the system,” Moran says.

The community health workers screen patients on the heart failure unit for social determinants, including food insecurity. MedStar partners with Hungry Harvest, which rescues fresh produce deemed “too ugly” for the supermarket. “We’ve been writing patients prescriptions for eight-week delivery of fresh produce,” Moran says, adding that community health workers also help patients find long-term sustainable options for food.

Moran, through MedStar, also is involved in Community Health in Action Taskforce (CHAT), an American Heart Association initiative project focused on vulnerable Baltimore communities disproportionately affected by cardiovascular diseases.

It’s all about connections, Moran emphasizes. And, he notes, it doesn’t require a large health system to cultivate such partnerships; his three hospitals are small to mid-size community facilities. The key is to connect, and “be willing and eager to be in a relationship with the community you serve.”

Tools are available to help organizations get started. For instance, the American Hospital Association offers clinicians and health systems its Community Conversations Toolkit at www.aha.org.

ROI: MAKING THE CASE

“Evidence gathered over the past 30 years supports the substantial impact of non-medical factors on overall physical and mental health,” asserted the American College of Physicians in its 2018 position paper (Ann Intern Med 2018;168[8]:577-8).

While that’s hardly a revelation for clinicians on the front lines of care, what may be surprising is that social interventions appear also to reduce overall spending and thus provide the potential for return on investment. Consider the following:

- A 2016 review found “substantial evidence of improved health outcomes and/or reduced health care spending related to interventions that addressed housing, nutrition, income support, and care coordination and community outreach needs” (PLoS One 2016;11[8]:e0160217).

- A 2018 study found a 10 percent reduction in healthcare costs for people successfully connected to social services compared to a control group. “Organizations that integrate medical and social services may thrive under policy initiatives that require financial accountability for the total well-being of patients,” the researchers concluded (Popul Health Manag 2018;21[6]:469-76).

- A 2018 analysis concluded that delivering food to nutritionally vulnerable patients can reduce the use of costly health services and decrease medical spending among those patients (Health Aff [Millwood] 2018;37[4]:535-42).

Given the move toward value-based payment models, it makes good business sense to focus on the patient’s total health and well-being to improve outcomes and reduce avoidable readmissions, Jaff says.

Ultimately, it will pay off, Moran says. “These are not quick fixes, and I think you have to be OK with that,” he explains. “But this is a long game, and we are seeing differences can be made and that we can change outcomes both from a financial and clinical perspective.”

It does require initial investments. There are corporate and government grants that help fund these efforts. Jaff encourages hospitals and health systems to think creatively about public/private partnerships. “Engage with local industries and workforces to collaborate on ways to make their communities healthier,” he counsels. He’s in the midst of doing that himself.

Still, in an era of razor-thin budgets, deciding to focus on the community involves tradeoffs. “There are so many things I wish I could do. I’d like to build a new building every five years. I’d like to build new ambulatory facilities out in our communities. I’d like to expand certain services by hiring more doctors and nurses and techs. But unfortunately, we need to make tough choices,” Jaff says. “Being here for the community is a long game for us because, frankly, it’s what we ought to be doing. It’s part of our DNA.”