Definitions, Documentation & the Dangers of Mislabeling: Is a Heart Attack Always a Heart Attack?

Troponin has become a widely accepted cardiac biomarker for myocardial infarction patients admitted to emergency rooms. But just how reliable is troponin in determining if a heart attack is really a heart attack?

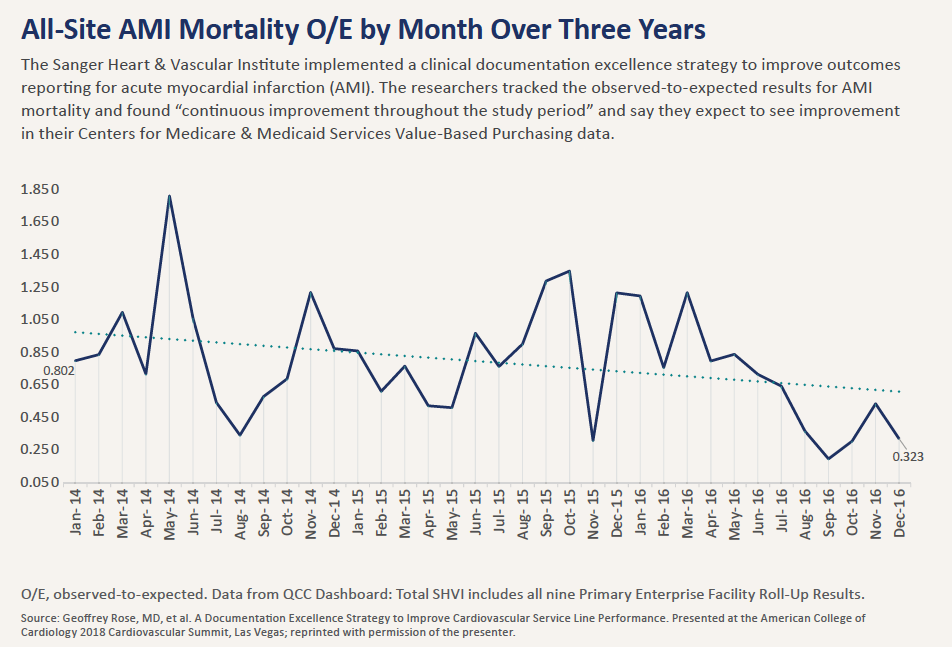

Geoffrey Rose, MD, was at once surprised and distressed. The 2014 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) data that rolled into Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute, part of Atrium Health, where he is chief of cardiology, reported an unexpectedly high rate for 30-day acute myocardial infarction (AMI) mortality. The claims-based data were a statistical blot at wide variance with the clinical data Sanger had manually abstracted from charts and routinely reported to registries as part of its quality program.

Determined to find the root cause, Rose and his team reviewed the records of 236 patients admitted in 2014 who were classified as AMI mortalities. The startling result: In roughly 30 percent of the cases, AMI should not have been designated as the principal diagnosis for inpatient admission. “We believed ourselves to be a high-performing organization,” explains Rose, “so when we saw the disconnect between our internal and external assessments we knew this was a problem we had to fix.”

An isolated case of clinical documentation confusion? In fact, the problem may be a lot more common and serious than most hospitals realize, with potential repercussions for their quality and performance metrics and even their bottom lines as healthcare moves inexorably to value-based care and new payment systems.

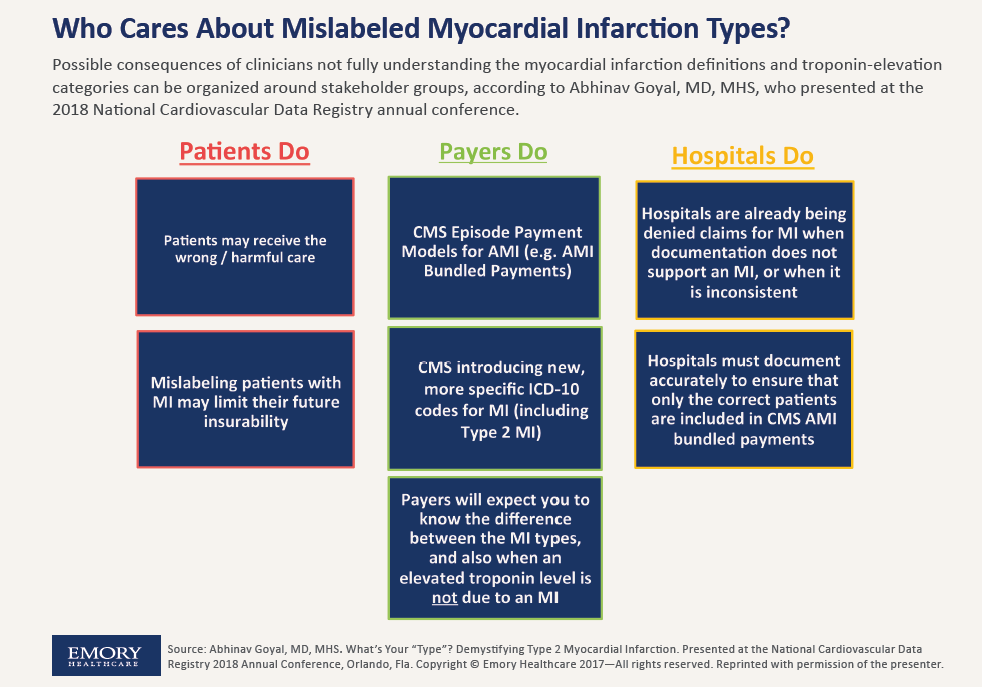

“It’s a problem that results from many clinicians not having a nuanced understanding of the different types of MI and the different categories of cardiac troponin elevation,” explains Abhinav Goyal, MD, MHS, chief quality officer in the cardiology division at Emory Healthcare, based in Atlanta, who began probing the issue with his colleagues in early 2017, when CMS announced episode payment models (particularly bundling) for AMI. “This has translated into a very widespread documentation problem that is impacting hospitals all over the country—and probably around the world.”

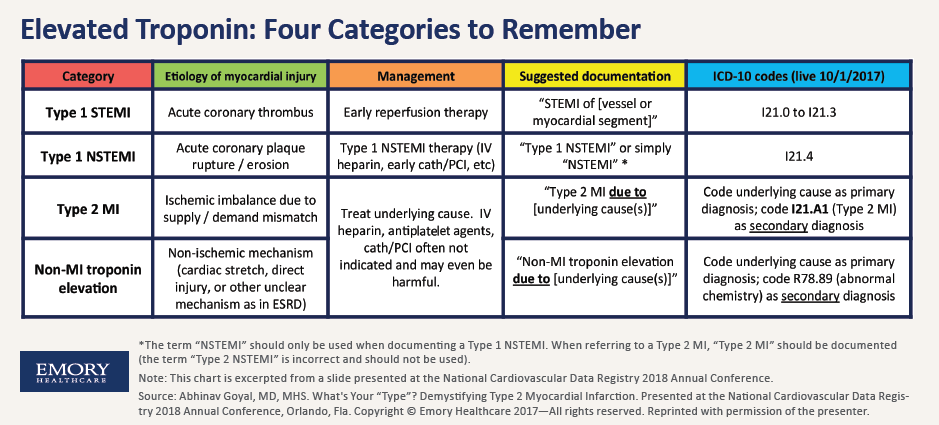

The problem is as much definitional as it is documentational. To put it in context, 2013 American College of Cardiology (ACC) guidelines point out that, while all troponin elevations indicate myocardial cell injury, only a subset can actually be classified as MI, indicating injury due to an ischemic mechanism (J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61[4]:485-510). The MI group includes:

- Type 1 STEMI, where rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque occurs and leads to complete occlusion of the coronary artery;

- Type 1 NSTEMI, where rupture or erosion of an atherosclerotic plaque occurs and leads to incomplete occlusion of the coronary artery; and

- Type 2 MI, due to increased oxygen demand or decreased oxygen supply triggered by such heterogenous causes as coronary spasm, coronary endothelial dysfunction, arrhythmia, anemia, respiratory failure, shock or severe hypertension.

In the non-MI troponin elevation group, however, ischemia is not even a factor. Instead, the cell injury is typically due to blunt trauma to the heart, defibrillator shock that stuns the heart or inflammation of the heart muscle.

The disconnect for hospitals often begins from the moment a patient is rushed into the emergency department with a heart attack. Many physicians fail to recognize the heterogenous causes of a Type 2 MI, a problem exacerbated by the lack of specificity in the CMS ICD-10 coding scheme. As a result, physicians often reflexively label patients with a Type 2 MI as having a Type 1, relying on elevated troponin to support their diagnosis.

“The problem is that we often use troponin as a surrogate for acute MI, when in reality a patient’s troponin can be elevated for a number of reasons, only a subset of which are related to actual blockages in the arteries around the heart,” explains Karen Joynt Maddox, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of medicine in the cardiovascular division at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “I suspect there is a lot of confusion about what people are supposed to be doing.”

A major revision in October 2017 of the ICD-10 coding system will undoubtedly heighten awareness among the clinical community of Type 2 MI and set the stage for better classification after a patient is admitted. In addition to creating a category for Type 2 MI, the new diagnostic codes differentiate the varieties of Type 1 MI (STEMI and NSTEMI) and add new codes for non-MI causes of troponin elevation and for “other MI types.”

The perils of mislabeling

The reason this granularity is so important? The profusion of pitfalls awaiting hospitals if patients are not properly coded. One of the most serious is that patients mislabeled as Type 1 could potentially receive harmful treatment with Type 1 therapies. For example, according to a scenario outlined by Goyal and his Emory Healthcare colleagues, a patient exhibiting high troponin due to a hypertensive emergency (a Type 2 MI) might be started on intravenous heparin for a presumed Type 1 coronary plaque rupture (a Type 1 NSTEMI), even though intravenous heparin is usually contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Incorrect documentation of MI types can also lead to denial of claims by payers as well compromise patients’ future insurability.

Another big reason coding accuracy matters is financial. The CMS Hospital VBP Program rewards or penalizes acute care hospitals on such performance measures as mortality and complications. And when a patient is mislabeled as Type 1—a designation that can remain with him or her throughout the hospital stay and be dutifully employed by coders preparing the discharge summary—that information can adversely impact the hospital’s 30-day AMI mortality data compiled by CMS as well as its HospitalCompare.gov scores available for public consumption. That’s what happened at the Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute. Had the 30 percent of its cases classified as AMI deaths been properly excluded from the AMI mortality data-set, according to Rose, Sanger would have achieved top decile VBP performance for AMI mortality in 2014.

Even MIs reported as Type 2 can significantly impact a hospital’s performance metrics. At a 2017 ACC Cardiovascular Summit presentation, Jason Wasfy, MD, director of quality and analytics at Massachusetts General Hospital Heart Center and a bundled payments expert, showed how Type 2 MI, often referred to as “troponin leaks” among physicians, could potentially raise the incidence of AMI mortality for a hospital. “These patients tend to be older and sicker and have poorer prognoses over the long run,” he says. “As a result, including these patients may worsen hospital performance on some of the quality metrics.”

Getting the documentation right

Alarmed at what his own in-house sleuthing had uncovered, Rose’s team took swift action. They undertook a clinical documentation excellence strategy to reconcile the differences between clinically coded and chart-abstracted data. Helping to drive that effort is a clinical documentation improvement (CDI) team that now reviews the records of all patients with a principal diagnosis of AMI before final billing.

A second part of the strategy is a “concurrent coding process” that promotes real-time collaboration between the CDI team and coders while the AMI patient is still in the hospital. This process, Rose explains, is designed to “break down the silos” that typically exist between hospital personnel responsible for coding, documentation and billing and the clinicians so that everyone is essentially on the same page.

As Goyal with Emory Healthcare, which launched last year its own clinical documentation improvement program, puts it, “The coders can really help us by notifying the providers if they see inconsistencies so that we can correct the documentation. And it needs to be done real time so we’re not trying to adjudicate this after the bills have been submitted.”

For both Emory and Sanger, their CDI investments are already paying dividends in the form of continuously improving their observed-to-expected (O/E) mortality ratios for AMI. (For Sanger, the O/E ratio fell from 0.79 in 2015, to 0.66 in 2016, to 0.53 through September 2017.) At the same time, new sensitivity to documentation has opened the door to other improvements that are helping to raise the quality of care for heart patients. Hospitalists and internal medicine providers at Sanger/Atrium, for example, are now tightly linked to the effort to improve AMI mortality, and an AMI continuum of care has been developed to catalog all clinical activities that need to take place around the patient.

“We think this is a logical approach,” says Rose, “that requires many who haven’t customarily worked together to find new ways to become part of a cohesive team.”